[page 159]

DETAILED MEMORANDUM ON THE PRINCIPAL EXAMINATIONS, OTHER THAN INTERNAL, TAKEN BY PUPILS OF SECONDARY SCHOOL AGE

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

Any description of the present state of external examinations in Secondary Schools falls naturally into two divisions. In the first place, it is necessary to describe each of the existing examinations taken by itself; and in the second, to describe the relation of these various examinations to each other, and the effect of their combined action on the schools which prepare for them. In Chapter II of this Report we have dealt with the present state of things from the latter point of view; but in view of the great length to which a detailed description of the separate examinations must necessarily extend we have thought it best to give this in a separate memorandum.

In this account of the existing external examinations in Secondary Schools, it has been found convenient to divide them into the following groups:

(1) "Local" and "School" examinations (including the inspection of schools by the examining bodies);

(2) University examinations (i.e. examinations which form part of a degree course);

(3) Civil Service Examinations;

(4) Army Entrance Examinations;

(5) Navy Entrance Examinations;

(6) Preliminary examinations of Professional bodies (including the Board of Education's Preliminary Examination for the Certificate);

(7) Examinations in Special Subjects, such as Music, Drawing, Science, Commercial Subjects, etc.;

(8) Examinations conducted by Local Education Authorities;

(9) Scholarship Examinations;

(10) Entrance Examinations.

It should be understood that we do not pretend to include all the external examinations which exist today. We are dealing only with those which directly affect Secondary Schools, and which are of some considerable importance. We omit, therefore, those whose annual number of candidates is quite small; those whose candidates, though of Secondary School age, do not enter from Secondary Schools; and those whose candidates are as a rule over 19 years of age. Further, in the case of examinations recognised or conducted by such bodies as the General Medical Council and other professional bodies, only the entrance or qualifying examinations are considered. The subsequent technical examinations of students and apprentices during the

[page 160]

course of their special and professional training are ignored. A summary of the examinations which are included in our consideration will be found in Appendix C, together with figures showing in statistical form the age and number of the candidates in the year 1908, and the date at which each examination was started. It is obvious that there are cases in which it was rather doubtful whether any particular examination should have been included in this list or not. In such cases of doubt we have added an explanatory note as a warning.

It may be explained that, for the most part, this statement is based on the published regulations of the examining bodies, supplemented in some cases by the evidence of witnesses. Where these sources of information have been insufficient, special inquiries have been addressed to the examining bodies, and we have to record our indebtedness to these bodies for the readiness they have shown in supplying us with the particulars needed. At the same time we desire to make it clear that, while these bodies have been good enough to assist us in this way, they are not in any way responsible for the manner in which the information with regard to the various examination is stated in this memorandum. Statistics as to the numbers of candidates at the various examinations have been given, where available; they do not all refer to one and the same year, but have in each case been brought as far as practicable up to date. It is possible that in some cases later figures than those given might have been obtained by application to the bodies concerned, but we have not felt justified in troubling them again for this purpose.

Finally, we would add that while the greatest care has been taken in setting out the conditions of the examinations, we cannot of course guarantee that some small inaccuracies may not have crept into this statement. Moreover, in view of the fact that frequent changes take place in the regulations of the examinations, it is important that candidates or others desiring information in regard to any particular examination should in every case consult the latest issue of the regulations themselves. It should be remembered that the purpose of this memorandum is to give a general description of the system of external examinations in Secondary Schools as a whole, and not to provide a substitute for the detailed regulations.

(1) "Local" and" School" Examinations

(a) THE OXFORD LOCAL EXAMINATIONS DELEGACY

The examinations conducted by the Oxford Local Examinations Delegacy fall into three groups: (i) those which are really local examinations, i.e. examinations at local centres, on which certificates are given; (ii) those which are really school examinations, i.e. examinations held in schools on the school syllabuses, no certificates being given; (iii) Combined School and Local Examinations, i.e. examinations which are held at schools,

[page 161]

but in which the examination papers are those used simultaneously in the Local examinations, certificates being given to those pupils who are candidates for them, and satisfy the examiners. The examinations in the first group are four in number, viz. (i) the Preliminary Local Examination; (ii) the Junior Local Examination; (iii) the Senior Local Examination; (iv) the Higher Local Examination. The examinations in the second group follow the varied requirements of each school that asks for such examinations. The examinations in the third group are three in number, viz. those in which the candidates wish to obtain (i) the Junior School Certificate; (ii) the Senior School Certificate: (iii) the Army Leaving Certificate.

We will now take these examinations in order.

(i) The Oxford Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Locals

The Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Local Examinations of the Oxford Delegacy are conducted under one set of regulations and may be treated as a whole. The Higher Local is on a different footing; and can be treated later by itself.

The Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Examinations are held in July of each year at Local Centres. A supplementary Junior and Senior Local is also held when needed in March. A local centre is only appointed on the application of a Local Committee, who must be prepared to undertake all the expenses which are occasioned by the examination being Local, i.e. by the candidates being examined at that particular centre instead of going to Oxford for the purpose. Examinations are held only at centres from which the amount received in fees reaches a certain minimum. Each committee appoints a local secretary, who acts generally as their agent. Centres are, as a rule, intended for all the candidates in the locality; but they may be confined to the pupils of a given school. The examination at such a school, however, remains a Local examination, and does not become a School examination. The number of local centres in England and Wales for the examinations of the Oxford Delegacy in 1910 was about 350; but the number of towns in which these centres were situated was only about 250, it being no uncommon thing for several centres to be appointed in the same town. It will be seen by a reference to Appendix B that these local centres are distributed over the whole of the country.

Candidates pay two separate fees, one to the Delegacy, and one to the Local Committee to defray local expenses. The fees to the Delegacy for ordinary candidates are as follows: for the Preliminary, 10s. 6d. [52p½] a candidate; for the Junior and Senior, £1 a candidate. The fee paid to the Local Committee varies according to the circumstances of the locality. Special fees are required for special papers on approved alternative

[page 162]

syllabuses, and for oral examinations in modern languages, and are described later.

The subjects comprised in the examinations are as follows:

In the Preliminary Local -

1. Arithmetic

2. Religious Knowledge.

3. English History.

4. English.

5. Geography.

6. Latin.

7. Greek. |

8. French.

9. German.

10. Italian.

11. Spanish.

12. Mathematics.

13. Higher Mathematics. |

14. Botany.

15. Experimental Science.

16. Chemistry.

17. Heat.

18. Domestic Economy.

19. Drawing. |

In the Junior Local the list of subjects is generally the same as that of the Preliminary, with the addition of Music, Bookkeeping, and Political Economy. Further, the History syllabus includes Ancient, General, and Foreign History, as options; Physics takes the place of Heat, and Domestic Economy is amplified and entered as Hygiene. Chemistry includes practical as well as theoretical work.

In the Senior examination, the list of subjects is very similar to that of the Junior. The Elements of Logic is added to the Political Economy section; Experimental Science is omitted; and Domestic Science* and Needlework* are added.

The syllabuses of the various subjects of examination are left fairly wide; but the following limitations may be noticed. In Religious Knowledge the syllabus for all three examinations consists entirely of set books. In History, candidates have the option of various periods, but they have the opportunity of showing knowledge of English History outside the period which they select. The English syllabus consists of English Composition, English Grammar, and English Literature. Neither Composition nor Grammar are compulsory, but appear as a matter of fact to be generally taken. The English Literature syllabus only contains various options in set books, except in the Senior Examination in which candidates may take a paper on General Literature* with a large choice of questions. In Latin and Greek, and (except in the Senior Examination) in French and German, set books or unprepared translation may be taken at the option of the candidate, higher marks being given for the latter. There are no set books in modern foreign languages for Senior candidates, who must offer unprepared translation and free composition as part of their examination. In Political Economy certain text-books are recommended. In Music, Drawing, Mathematics, and Science subjects, syllabuses are issued, but they are of a very general character.

It should be added that candidates in schools may offer themselves for an oral examination in French or German on payment of a special fee of 2s. 6d. [12½p] a candidate, provided that

*These are new subjects for 1912.

[page 163]

the minimum payment from anyone school is £1, and that the travelling and hotel expenses (if any) of the examiners are paid. Success in the oral examination does not count towards a "Pass" in the language, but is mentioned on the certificates of successful candidates who pass in the written work. It is also taken into account in deciding questions of Honours and Distinctions. The number of candidates who take the oral examination is not published, but unless the percentage of failures is quite unlike that in any other part of the examination the number must be very small. The following are the numbers of candidates who in 1908 passed the written examination in French or in German; passed the oral examination, and also obtained a certificate: French: Seniors 67, Juniors 51, Preliminary 0; German; Seniors 11, Juniors 3, Preliminary 0. In Science subjects there is no practical examination in the Preliminary Examination. In the Junior and Senior Examinations, candidates cannot pass in Chemistry, nor in the Junior Examination in Experimental Science, without satisfying the examiners in the practical part of the examination. The practical examination, however, can only be taken where the laboratory accommodation of the Centre allows of it. There is no practical examination in any other Science Section, nor in Music, but the paper in Physics assumes that candidates have been through a course of experimental instruction.

It should be mentioned that the syllabuses of the various subjects of the examination are prepared and issued by the Delegacy. They are not directly related to the curricula of the schools. But the Delegacy have informed us that they have from the first been in full communication with the schools that habitually send in their pupils for the examination, and that the developments of the original system which have taken place have all been of a nature to render closer the connection between the Delegacy and the schools. This connection, however, appears to be only of an indirect character in the majority of cases, as the teachers take no part in the examinations. The Delegates are prepared, however, to consider applications for alternative syllabuses and special papers, subject to extra payment being made for setting and printing the paper. This charge is not less than £2 2s. [£2.10] for each paper. There is also an Advance Fee of £2 for a special Senior or Junior paper, or £10 10s. [£10.50] for a special Preliminary paper, but if more than one such paper be supplied the advance fee is only £2 for each paper after the first. A group of schools may combine to make a joint application for special papers, provided all the candidates concerned are entered at the same Local Centre. We have no information as to the extent to which these special papers are applied for in the case of the examinations under consideration, but we believe it to be very small. In practice nearly all the candidates follow the examination syllabus of the Delegacy and take the ordinary papers.

[page 164]

As regards choice of subjects, candidates have an almost unfettered option. To obtain a certificate in either of the three examinations, candidates must pass, at one and the same examination, in at least five sections. In the Junior Examination they must also pass in Dictation. All candidates (unless they or their parents object) must, by the Statutes of the University, be examined in at least one of the divisions of Religious Knowledge. In the Senior Examination a candidate may not take more than one of the three following subjects, viz. Book-keeping, Needlework, and Drawing. With these exceptions, candidates are at liberty to take any combination of subjects they like, subject, however, to the exigencies of the time table, which, speaking generally, may limit the options slightly within each subject, but has little effect on limiting the choice of subjects as a whole. In practice, however, though the candidates have the option of devising eccentric combinations of subjects, it is not found that they do so. The subjects actually chosen by the 8,362* candidates who entered for the Junior Local Examination in 1908, arranged in the order of the candidates' preference, are as follows, the numbers in brackets showing the number of candidates who took each subject:

Arithmetic (8,249).

English Language and Literature (8,215).†

History (8,151).

Religious Knowledge (8,092).

Geography (7,626).

French (7,301).

Mathematics (6,632).

Drawing (5,519).

Physics (say 2,000).†

Latin (1,947).

Botany (1,467).

Chemistry (1,161).

Experimental Science (644).

Political Economy, etc. (say 600).†

*This and the following figures are taken from the Annual Reports of the Delegacy, and show the numbers actually examined, excluding those who entered their names but did not attend the examination. A table supplied by the Delegacy, and giving statistics of the examinations since their establishment, is printed on page [blank] (in Volume II); it will be noticed that those figures differ slightly from those given here.

†In these cases the exact figures cannot be ascertained from the tables published by the Delegacy, as the number of candidates taking the different divisions of a section are given instead of the number of separate candidates who took the section as a whole. Thus, in the section called English Language and Literature, the number of candidates who entered for the section is not given, but only the numbers who entered for each of the three divisions: Composition (8,180), Grammar (6,623), and Literature (8,215). It appears from these figures that, practically all the candidates took both Literature and Composition, and that three-quarters of them took Grammar as well. In the section called Political Economy, etc. there are three divisions: Political Economy (295), Elementary Politics (238), and Historical Geography (150). No candidate may combine the first two divisions, so that at least 533 separate candidates must have taken this subject. We have assumed [footnote continues on next page]

[page 165]

Hygiene (586).

German (424).

Higher Mathematics (411).

Book-keeping (373).

Greek (258).

Music (182).

Italian or Spanish (35).

From these figures it is seen that practically the whole of the candidates took Arithmetic, Religious Knowledge, History, and English Literature, about 91 per cent took Geography, about 87 per cent took French, about 79 per cent took Mathematics, and about 66 per cent took Drawing. It is not possible to say how many candidates took one or more Science subjects; but, with this exception, it is clear that the majority of candidates took most of the ordinary subjects of a good general education which can be tested by a paper examination.

A very similar result is obtained by an analysis of the subjects taken by the 9,384* candidates at the Senior Local in 1908. The following list shows the subjects in the order of the candidates' preference, with the number who took each:

English Language and Literature (9,191).†

Arithmetic (9,156).

History (9,070).

Religious Knowledge (8,794).

Geography (8,196).

French (6,249).

Mathematics (6,035).

Drawing (5,956).

Physics (say 2,500).†

Botany (1,491).

Latin (1,216).

Chemistry (991).

Political Economy, etc. (say 850).†

Hygiene (607).

German (453).

Footnote - continued

that half the candidates who took Historical Geography combined that subject with one of the others, making a total of about 600 separate candidates who took the section as a whole. Under the section Physics are included Mechanics (367), Heat (1,419), Sound and Light (298), Electricity (536). Candidates can pass in the section as a whole by passing in one division; can only obtain distinction by passing in two; and are not allowed to take more than three. It is probably a fair estimate to suppose that about 2,000 separate candidates entered for some part of the Physics section.

*See note * on page 164.

†See note † on preceding page. Similar remarks apply to these subjects in the Senior Examination, the figures for the separate divisions being as follows: English: Composition (9,104), Grammar (5,123), Literature (9,191). Political Economy, etc.: Political Economy (389), Politics (103), Historical Geography (725). Physics: Mechanics (632), Heat (1,179), Sound, Light, and Heat (934), Electricity (656).

[page 166]

Higher Mathematics (271).

Book-keeping (230).

Greek (226).

Music (208).

Italian or Spanish (29).

Here, again, it is seen that practically all the candidates take English, Arithmetic, and History. About 87 per cent take Geography, about 67 per cent take French, about 64 per cent take Mathematics, and about 63 per cent take Drawing. The number who take one or more Science subjects cannot be ascertained from the published figures. It is worth noting that the number of candidates who take two languages must be exceedingly small. Only 1,216 candidates take Latin, while Greek is almost ignored.

The number of candidates using these examinations is very large, and recent years have seen an enormous increase, particularly in the numbers who take the Senior Local. From 1,940 in 1900, the number of Senior candidates had risen to 10,980 in 1909. The number of Junior candidates has also increased, though not so rapidly, being 4,479 in 1900 and 8,751 in 1909. On the other hand, the number of Preliminary candidates, which rose to its highest (4,256) in 1904, has since then steadily decreased, being only 3,438 in 1909.* This decrease is owing mainly to the action of the Board of Education. Section 5 of the Regulations of 1904 forbade scholars in the first or second year of the course (except by the express permission of the Board) to sit for any external examination except one which comprised the whole school, or one held solely for the award of scholarships or exhibitions. In the current Regulations, this prohibition is applied generally to all pupils under 15 years of age. Local Authorities also appear to be moving in a few cases in the same direction.

As regards the ages of candidates, the Preliminary Examination is confined exclusively to candidates below 16 years of age. Further, only candidates under 14 are eligible for Honours or Distinction. In the Junior and Senior Locals there is no limit of age for ordinary candidates, but candidates are not eligible for Honours or Distinction unless they are under 16† or 19 years of age respectively.

The results of each of the three examinations are published in two lists, Honours and Pass. In both cases the names of the successful candidates are given together with the name of their school and its Principal. In the Honours lists the names of candidates are arranged in three classes, the first two in order of merit‡ and the third in the order of their Index Numbers

*See note * on page 164.

†Raised to 17 for the 1912 examinations.

‡In and after 1911, the names of those in the Second Class will be placed in "not more than five Divisions".

[page 167]

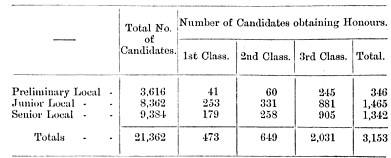

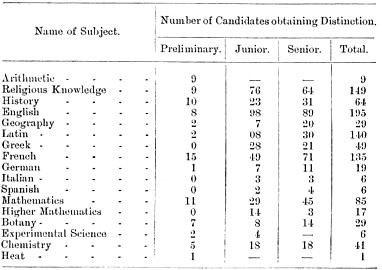

under the several Centres. The following table shows the number or candidates who obtained Honours in the year 1908:

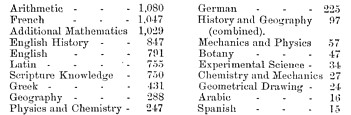

In the Pass Lists are included the names of all other successful candidates. They are arranged in two divisions in numerical order under the several Centres. In the first division are the names of candidates not over 14, 16,* or 19 for the Preliminary, Junior, and Senior respectively. In the second division are the candidates over those ages, who receive Over-age Certificates. At the end of the Pass Lists are separate lists of candidates who (having obtained certificates) earned distinction in individual subjects. The names are given in order of merit. The following table shows the number of distinctions obtained in each subject in each of the three examinations in 1908:

TABLE SHOWING THE NUMBER OF CANDIDATES OBTAINING DISTINCTIONS IN THE OXFORD PRELIMINARY, JUNIOR, AND SENlOR LOCAL EXAMINATIONS, 1908

*Raised to 17 for the 1912 examinations.

[page 168]

In addition to the Division Lists, Supplementary Tables are published giving particulars as to the subjects in which each candidate satisfied the examiners. Unsuccessful as well as successful candidates are included in these lists, but the subjects which candidates took, but failed to pass in, are not shown. The Delegates are also prepared, on payment of a small fee, to inform heads of schools of the manner in which their pupils acquitted themselves in the several subjects, and also to place their pupils in order of merit, among themselves, in each subject and on the whole examination. In no case, however, are the actual marks obtained by the candidates made known.

The results of the examinations are also used for various other purposes. The Certificates are accepted, in varying degrees, by Universities and Professional bodies, as exempting the holders from various other examinations. A list of the exemptions granted to successful candidates at the Oxford Locals is given in Appendix D on pages 329 ff. In a few cases scholarships and prizes granted by schools or public bodies are awarded on the strength of the Senior and Junior Locals. Lastly, the Delegates themselves award four scholarships, each tenable for one year, as follows: One of £30 to the Senior boy candidate who is placed highest in the Honours List; one of £30 to the corresponding girl candidate; one of £10 to the Junior boy candidate who is placed highest in the Honours List; and one of £10 to the corresponding girl candidate.

(ii) The Oxford Higher Local Examination

The Higher Local Examinations are held twice a year, in July and November. The July Examination is held at the same time as the other three Local Examinations, and at any local centre where satisfactory arrangements can be made. The November Examination is held at Oxford and at other places appointed by the Delegates after application has been made on behalf of candidates wishing to be examined.

A fee of £1 10s. [£1.50] is payable to the Delegates on the first time of entry, and of £1 on each subsequent occasion, in addition to local fees.

[page 169]

The subjects of the examination are divided into 11 sections, viz.

Arithmetic

A. Languages (Latin, Greek, French, German, Italian).

B. Religious Knowledge.

C. Modern History.

D. Mathematics.

E. Logic, Political Economy, and Psychology. |

F. English.

G. Music.

H. Natural Science.

K. Geography.

L. History and Theory of Education. |

The choice of subjects open to candidates for certificates is much more restricted than in the case of the Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Locals. Arithmetic is obligatory for all candidates. For an ordinary certificate a candidate must pass in three other sections, of which one must be either Languages, or Mathematics, or Natural Science. For an Honours Certificate the rules are the same as regards obligatory sections, but candidates who pass in only three sections (in addition to Arithmetic) must obtain a First or Second Class in two of the three sections. Those who pass in four sections must obtain a First Class in one of them.

Another point which differentiates the Higher Local from the Preliminary, Junior, and Senior is that candidates need not pass in all the subjects required for a certificate at one and the same examination.

As regards the syllabuses, they are on an altogether higher plane, both as regards the quality and quantity of the work demanded, than those of the Senior Locals. In Modern Languages knowledge of the outlines of a period of literature is required, in addition to grammar, translation, and set books. History includes the general outlines of English History, from 1066 to 1837, as well as a set period of either English or Foreign History. In English the outlines of the History of a period of English Literature are set, together with certain prescribed books a knowledge of which postulates a fair amount of accurate general reading. In Natural Science candidates must pass in either Chemistry, or Physics, or Botany. The syllabus in Geography is very comprehensive, and a point is made of the relation of the subject to Natural Science and History. There is a practical examination in Chemistry, but none in any other Science subject nor in Music. In Modern Languages, there is an optional viva voce examination for candidates who go specially to Oxford for the purpose. In all languages set books are obligatory.

The syllabuses are, of course, drawn up by the Delegates. No alternative syllabuses or special papers are allowed.

There is no limit of age for candidates taking the Higher Local; but the number of candidates is very small, amounting in 1908 only to 282, of whom only 76* obtained Certificates, and

*Excluding those who, although they passed in certain groups, did not complete their certificates, and those who had already gained a certificate and now added to their successes.

[page 170]

of whom 36 were awarded an Honours Certificate. The examination is used almost entirely as a means of admission to the Women's Colleges at Oxford. The only other bodies which actually grant exemptions to the holder of a Higher Local Certificate are the Scottish Universities, the universities of Wales and Birmingham, the Board of Education, the General Medical Council, and the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. In view of the quality of the examination, however, we assume that the only reason why more public bodies have not granted facilities to successful candidates is that there has been no demand for such facilities from the candidates.

(iii) "School" Examinations conducted by the Oxford Delegacy

It has already been explained that the Local Examinations are organised in terms of Centres and not of Schools. Practically the whole of the candidates, of course, come to the examinations direct from schools, and the schools not only prepare their pupils for the examinations, but, as already explained, are enabled, on payment of a small fee, to obtain from the Delegates a certain amount of information as to the way in which their pupils have acquitted themselves in the several subjects in which they pass. But the Local Examinations are not "School" Examinations in the sense in which the Delegates use that word. In a "School" Examination, properly so called, no certificates are given; the examination is held only in such subjects as are selected by the school authorities; the examination papers are prepared on the school syllabuses, either by the Delegates' examiners, or by the teachers themselves subject to criticism by the examiners; similarly the answers are marked either by the staff or by the examiners; in either case the answers are reported on by the Delegates' examiners. The Delegates are prepared to conduct at least a part of the examination viva voce, and do, as a matter of fact, usually find that the authorities of schools desire that this should be done.

A variant of the School Examination is what is known as a Combined School and Local Examination. Such an examination is conducted partly or wholly by means of papers which are being used simultaneously in the Preliminary, Junior, Senior, or Higher Local Examination, and the school or group of schools is formed into a Special Local Centre. The examination appears to be essentially a Local Examination. Candidates are eligible for certificates on paying the prescribed Local Examination fee, and the superintendence of the examination and the setting and marking of the papers is entirely managed by the Delegates. The examination differs, however, from an ordinary Local Examination in two main respects: pupils who are not candidates for certificates may attend the examination, and further, the worked papers of all candidates may be treated for school purposes; that is to say, the marks obtained are forwarded to the school

[page 171]

and a report is made to the school on the work of all the candidates. The advantages claimed for the system are that pupils who take part in a school examination can obtain a certificate without undergoing a second examination; that examination papers can be supplied much more cheaply than if each had to be set on a special syllabus for each school; and that uniformity of standard is secured. We feel, however, that as a mere matter of fact the examination is not really a school examination at all. It is divorced from the school syllabuses, and the teacher takes no direct part in it. It does not really enable candidates to get a certificate on a genuine school examination, and does not save them from an external examination. It allows them to use an external examination for school purposes. It does not allow them to use a school examination for external purposes. While, however, the Combined School and Local Examination omits the best features of the school examination proper, it admits a much closer relation between the Delegates and the school authorities than the ordinary Local Examination.

The Annual Report of the Delegacy contains a list of 78 schools "examined or inspected" during the year 1909.

Charges are made at the following rates: For each paper specially set (normally), 15s. [75p]; for each paper not specially set, or for each Higher Local paper used, 5s. [25p]; for each Senior or Junior Local paper used, 3s. 6d. [17½p]; for each Preliminary Local paper used, 2s. 6d. [12½p]; for each exercise looked over, 1s. 9d. [8p], 6d. [2½p], or 4d. [2p] for Higher, Senior, Junior, or Preliminary Local papers respectively; for other papers, 6d. each; for inspecting and reporting upon answers already marked by the staff, £1 per 100 exercises. For a viva voce examination, £2 5s. [£2.25] per day for each examiner employed.

(iv) Examinations for School Certificates

It will be plain from the above descriptions of the Local and the Combined Local and School Examinations of the Oxford Delegacy that the certificates granted for success in those examinations take no account of the candidates' school record. Candidates may come from a good school, a bad school, or (in the case of Locals) from no school at all. The certificate in fact is a record of examination success, and makes no claim to anything further, except, of course, so far as success in examination may be taken as an indirect indication of training. In order to provide a certificate which shall contain more direct evidence of sound education, the Delegates offer what are known as Junior and Senior School Certificates. The essence of these certificates is that they are only awarded to candidates who have attended continuously during a definite period of time schools which are specially approved by the Delegates for this purpose. An approved school in this connection means one which has been inspected during the last five years either by the Delegates or

[page 172]

by the Board of Education, or by an Inspecting Body accepted by the Delegates, the report on such inspection having been approved by the Delegates as satisfactory. It is hardly necessary to point out that the admission of inspection as one of the conditions in which the certificate is granted introduces a vitally important factor into the scheme.

The following brief account of the conditions on which these school certificates are granted will show the general nature of the scheme.

The Junior School Certificate is awarded to candidates who (1) have attended continuously for two years at least one or more schools approved for the purpose, and (2) have passed the Junior Local Examination in certain subjects, viz. (1) Dictation; (2) Arithmetic; (3) English Language and Literature, including Composition: (4) at least one language (Latin, Greek, French, German, Italian, or Spanish), together with at least three other sections, which must be selected from not less than two of the three following groups, viz. Group I, Religious Knowledge, History, Geography, Political Economy; Group II, Mathematics, Higher Mathematics; Group III, Botany, Experimental Science, Chemistry, Physics.

A Senior School Certificate is awarded to candidates who (1) have attended continuously for three years at least one or more approved schools, and (2) have passed the Senior Local Examination in a number and combination of subjects practically the same as those for Junior candidates (but not including Dictation), and (3) are not under 16 years of age.

In the case both of Junior and Senior School Certificates, if candidates have taken a sufficient course of instruction in Geometrical Drawing and Practical Drawing and in Practical Measurements, or have taken a sufficient course of laboratory work in one or more branches of Natural Science, these facts will be recorded on the School Certificate if one is gained. Further, a candidate who has obtained a certificate may have endorsed on it any additional subjects passed by him (in the same grade) whilst still at school.

It may be said generally that a School Certificate differs from an ordinary Local Examination Certificate in these particulars: a pass in at least six* subjects is required, instead of only five*; the combination of subjects is to a large extent laid down by the Delegacy instead of being entirely at the choice of the candidate; continuous residence at an approved school is an essential condition. On the other hand, it resembles the Local Examination Certificate in this, that it is based on an examination which is not a school examination, that is to say, which is not based on the school syllabus and the school methods of teaching.

Since in passing the Junior or Senior School Certificate Examination a candidate necessarily qualifies for a certificate

*i.e. without counting Dictation as a separate subject.

[page 173]

of the corresponding grade in the Local Examination, it follows as a matter of course that he is entitled to all the exemptions which are allowed in respect of the latter. In addition, a candidate who satisfies certain conditions in the Senior School Examination is exempted from Responsions.

The fees are the same as for candidates for the Junior and Senior Locals, with the addition of a special fee of £1 for (any number of) candidates for Junior School Certificates at any one school, and a similar fee for any number of Senior candidates.

The number of candidates for Senior School Certificates in 1908, 1909, and 1910 were respectively 11, 52, and 58, of whom 7, 30, and 23 passed; the numbers of candidates for Junior Certificates in those years were respectively 25, 10, and 5, of whom 8, 7, and 4 passed.

(v) Army Leaving Certificates

Army Leaving Certificates are granted by the Delegates in accordance with a scheme which will be described later. Candidates for these certificates must have entered for a Senior School Certificate, must have taken the papers of the Senior Local Examination in all the necessary subjects, and must have attained such standard of proficiency in them as is required by the Army Council.*

(vi) Inspection

The Delegates are prepared to conduct the inspection of schools, and they issue regulations dealing with the subject. In practice, however, very little is done, the number of schools inspected in 1905 having been 15; in 1906, 5; in 1907,4; in 1908, 3; in 1909, 6; and in 1910, 8. The Delegates believe that the probable reason for the slow development of this part of their work is the fact that they make a charge for conducting an inspection. The fees are as follows: £4 a day for each day spent in inspection on account of each inspector employed, with a minimum charge of £6 when only one inspector is appointed and a minimum charge of £4 each when more than one is employed. The inspectors' report is prepared without extra charge, but travelling and hotel expenses have to be defrayed by the school authorities.

(b) THE CAMBRIDGE LOCAL EXAMINATIONS SYNDICATE

We have dealt first with the Oxford Local Examinations merely because chronologically they were the earliest of the University Local Examinations. We have dealt with them in some detail because it did not seem possible otherwise to give an accurate general view of their working. In treating the

*Further information with regard to Army Entrance Examinations will be found on pp. 268 ff. It will be seen that the existing scheme is about to be discontinued, and that the last examination for Army Leaving Certificates will be held in the Michaelmas Term, 1911.

[page 174]

Local and School Examinations of other examining bodies we shall, so far as possible, abbreviate our description by dealing quite briefly with those points in which they do not differ from those of the Oxford Delegacy.

The examinations of the Cambridge Syndicate correspond in their general scope with those of Oxford. They are the Preliminary, Junior, Senior, and Higher Local Examinations, the School, and the Combined School and Local Examinations, and the examinations for Junior and Senior School Certificates, and Army Certificates.

(i) The Cambridge Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Local Examinations

These examinations are held twice a year, in July and December, at Local Centres in various parts of England and Wales. The centres, like those for the Oxford examinations, are established only in places where a local committee has been formed and has made application for the examinations to be held there, and where the amount of the fees reaches a certain minimum. The number of centres is about the same as in the case of the Oxford examinations (see Appendix B, pp. 311 ff.).

The normal fees of the Syndicate are the same as those of the Oxford Delegacy, namely, 10s. 6d. [52½p] for each candidate for the Preliminary Examination, and £1 for each Junior or Senior candidate. Special fees are charged for special papers on alternative set books and syllabuses, and for an examination in spoken French and German.

The subjects comprised in the examinations are as follows:

In the Preliminary Local:

Compulsory

(1) Writing from Dictation.

(2) Arithmetic

Optional

(1) Religious Knowledge.

(2) English.

(3) English History.

(4) Geography.

(5) Latin.

(6) French.

(7) German. |

(8) Geometry.

(9) Algebra.

(10) Experimental Science.

(11) Chemistry.

(12) Heat.

(13) Botany.

(14) Drawing. |

In the Junior Local:

Compulsory

(1) Writing from Dictation.

(2) Arithmetic

Optional

(1) Religious Knowledge.

(2) English Language and Literature.

(3) History and Geography.

(4) Latin. |

(5) Greek.

(6) French.

(7) German.

(8) Spanish.

(9) Dutch. |

[page 175]

(10) Mathematics (Geometry, Algebra, Plane Trigonometry, Elementary Mechanics).

(11) Elementary Experimental Science.

(12) Chemistry.

(13) Physics (Heat, Sound and Light, Electricity and Magnetism). |

(14) Biology and Physical Geography (Botany, Natural History of Animals, Physiology and Hygiene, Physical Geography).

(15) Book-keeping, Mensuration and Surveying, and Shorthand.

(16) Drawing.

(17) Music. |

In the Senior Local, the subjects correspond very closely with those of the Junior Local. The only differences are that Dictation and Elementary Experimental Science are omitted, Agricultural Science is added, and further divisions are introduced into some of the subjects.*

The syllabuses of the subjects of the examinations are drawn up and published by the Syndicate. The following points may be noted. The syllabuses in Religious Knowledge are confined entirely to short selected hooks. In English, the syllabus of the Preliminary includes (i) Grammar, (ii) Composition, and (iii) alternative set books, of which either Grammar or Composition is compulsory. In the Junior, the syllabus falls under the same headings, but neither Grammar nor Composition is compulsory except for candidates for distinction. In the Senior, Grammar is dropped, and the syllabus consists of (a) Composition which is compulsory for candidates for distinction, (b) alternative set books, and (c) a paper of easy questions testing the candidates' general knowledge of English Literature since 1579 A.D. The syllabus specially mentions that in this last paper, (c), the questions will not be limited to text book knowledge. The English History syllabuses are divided into periods, but candidates may take questions from any division of the paper, so that their choice appears to be quite unfettered. The Preliminary syllabus is confined to English History, but Roman History is included in the Junior, and either Roman or Greek in the Senior. In the Junior and Senior Examinations, History and Geography are included under one section. In the former, students cannot pass the section without taking Geography; in the latter, the section is practically divided into three groups, (a) History (History of England or History of the British Empire, or Greek or Roman History), (b) Geography, (c) Political Economy or Logic. As candidates only have to take two of these groups, they can pass the section as a whole though they omit either History or Geography altogether.

In Latin and Greek easy unprepared translation (with a vocabulary of unusual words) is compulsory for all candidates. Set books are also given, and the Syndicate attach great importance to them, though they allow candidates the alternative

*viz. In Mathematics - Analytical Geometry, Differential Calculus and Applied Mathematics (Elementary Mechanics being dropped). In Physics - Experimental Mechanics. In History, Geography, etc. - Political Economy and Logic. In Biology, etc. - Domestic Science.

[page 176]

of unprepared translation of ordinary difficulty. In French and German, the Preliminary syllabus consists only of easy translation and questions on accidence; in the Junior syllabus, a certain amount of unprepared translation is compulsory for all candidates; but set books may be taken instead of the more difficult unseen, for which, however, higher marks are obtainable. For candidates who take selected books, questions may be set on historical and geographical allusions, and upon the metre of verse subjects. The Senior paper consists of grammar and translation, with composition as an alternative to the harder portion of the latter.

In the Science subjects detailed syllabuses are published and can be obtained on application to the Syndicate.

It is worthy of mention that the Cambridge University Press issues annotated editions of all the set books mentioned in the syllabuses of the Local Examinations and prepares a special list of such works.

The examinations are not confined exclusively to paper work. Candidates for the Preliminary, Junior, or Senior Examinations can be examined in spoken French or German on payment of a fee of 2s. 6d. [12½p] apiece (with a minimum fee for any school or group of schools of £1 for each language together with the travelling and hotel expenses, if any, of the examiner or examiners). In 1909 the percentage of Junior candidates in French who took the oral examination was 15.3, and of Senior candidates 15.1. In German the percentages were 10 and 13.9. Candidates who pass in written French or German, and also in the spoken language, have the fact that they passed an oral examination endorsed on their certificates. Success in the oral examination, however, is not necessary for passing in the language, nor even for a mark of distinction, though it is taken into account in determining the place of candidates in the Class List, and is counted towards the mark of distinction in cases where the mark would not be obtained without it. In Chemistry and Experimental Science a practical examination is compulsory for all Junior and Senior candidates taking those subjects, without extra fee, and examinations in these subjects are held only at centres where there is a properly equipped laboratory. In Botany specimens are sent to the examination centres for dissection and description. There is no practical examination in Physics, but the questions are principally such as to test the candidates' knowledge of the subject as gained from a course of experimental instruction.

As in the case of the examinations of the Oxford Delegacy, the syllabuses of the Cambridge Locals are not based on individual school curricula; but examination papers on alternative syllabuses and set books may be set under certain conditions if a fee is paid by the school to cover the extra cost. We are informed that there is always a considerable number of former headmasters on the list of examiners, and that the Syndicate are

[page 177]

constantly receiving from the heads of schools informal suggestions and representations with regard to the examinations, and from time to time invite their opinions on subjects which they have under discussion.

As to choice of subjects, candidates have somewhat less discretion than is allowed in the Oxford Locals. Arithmetic is compulsory for candidates for the Preliminary and Junior and Senior Examinations, and Dictation is compulsory in the two former. At least a part of the section Religious Knowledge must be taken by all candidates, subject to a conscience clause. Further, candidates for the Preliminary Examination must pass in four of the fourteen optional sections enumerated above; they may not enter for more than five of the ten sections 5-14, or for more than two of the four sections 10-13, or for more than eight sections altogether. In the Junior Local, candidates must pass either (a) in three of the sections 1-14 (one at least of the three being section 2 or one of the sections 4-9); or (b) in two of the sections 1-14, together with two subjects out of any other two of these sections (one at least of the two complete sections being section 2 or one of the sections 4-9). In the Senior Local, candidates must pass in at least three of the sections 1-14, one at least of the three being section 2 or one of the sections 4-9. In the Junior and Senior Examinations no student may enter for more than seven sections, together with a part of an eighth section. In the case of all three examinations it is necessary, in order to qualify for a certificate, to satisfy the prescribed conditions at one and the same examination.

The following tables show the subjects of the examinations arranged in order of the candidates' preference, with the number of candidates who took each. The figures are for the year 1908*:

Junior Local. (Total Number of Candidates, 9,667.)

Arithmetic (9,665).

Dictation (9,665).

History (9,493).†

Geography (9,443).†

English Language and Literature (more than 9,320).‡

Religious Knowledge (9,112).‡

*They are taken from the Annual Report of the Syndicate, and, it is understood, refer to the total number of candidates entered, some of whom did not actually attend the examination.

†History and Geography are included in one section, for a pass in which it is necessary to take Geography and one of the divisions of History, of which there are three, viz. (a) History of England , (b) History of British Empire; (c) Roman History.

‡In these cases the correct figures cannot be ascertained from the tables published by the Syndicate, as the number of candidates taking the different divisions of a section are given instead of the number of separate candidates who took the section as a whole.

English Language and Literature. - The number given is the number who took Composition, but candidates had a choice of five divisions, of which [footnote continues on next page]

[page 178]

French (8,073).

Drawing (say 8,000).‡

Mathematics (7,583 - at least).‡

Latin (2,747).

Chemistry (1,850)‡

Physical Geography (1,430).*

Botany (1,284).*

Elementary Experimental Science (1,078).

Physics (1,067).‡

Music (962).

Book-keeping (917).§

German (709).

Physiology and Hygiene (451).*

Mensuration and Surveying (174).§

Greek (171).

Shorthand (170).§

Natural History of Animals (67).*

Spanish (33).

The total number of candidates entered having boon 9,667, it is seen that, with two exceptions (although these subjects were compulsory), all took Dictation and Arithmetic. As regards the other subjects, History, Geography, and English were each taken by over, and Religious Knowledge by just under, 95 per cent; French by about 84 per cent; Drawing by about 83 per cent; and Mathematics by about 79 per cent. These propor-

‡Footnote - continued.

they had to take two to pass (or three for distinction), and of which one had to be a book. The numbers taking the separate divisions, were as follows: (a) Composition (9,320); (b) and (c) Books (9,077); (d) Books (1,420); (e) Grammar (8,622). No candidate could take both (b) and (c) nor more than three subjects altogether. It is, therefore, certain that the number taking this section was in excess of that given above.

Religious Knowledge. - This is the number who took the Gospel, together with those who took Kings (Jewish students only). This division, with one of four others, was necessary for a Pass in this section.

Drawing. - This section is divided into four subjects of which two are required for a Pass. The numbers in the separate subjects are as follows: (a) Freehand (6,894); (b) Model (6,195); (c) Geometrical (2,975); (d) Elementary Design (825). A candidate was not allowed to take both (c) and (d). Supposing each candidate had taken two subjects and only two, the number of individual candidates would have been about 8,500.

Mathematics. - This section has four divisions, of which each candidate must pass in Geometry and Algebra. The number given above is that of the candidates who took Algebra, which was in excess of the number who took Geometry. The numbers were as follows: (a) Geometry (7,206); (b) Algebra (7,583); (c) Trigonometry (1,113); (d) Mechanics (291).

Chemistry. - Candidates had to pass in both Theoretical and Practical Chemistry. The numbers were (a) Theoretical (1,850), as given above; (b) Practical (1,701).

Physics. - Candidates had to pass in two out of three subjects. The numbers were as follows: (a) Heat (1,067), given above , (b) Sound and Light (362); (c) Electricity and Magnetism (702).

*These four subjects are all contained in one section, called "Biology and Physical Geography".

§These subjects are all contained in one section, only one subject is needed for a pass; no candidate may take both Shorthand and Mensuration.

‡See footnote commencing on page 177.

[page 179]

tions are for the most part very similar to those noticed in the case of Oxford (see page 165).

Senior Local. (Total number of candidates, 7,363)*

Arithmetic (7,362).

English Language and Literature (7,130 - at least).†

History (6,995).‡

Geography (6,728).‡

Religious Knowledge (6,652).†

French (5,134).

Drawing (say 5,000).†

Mathematics (4,534 - at least).†

Physical Geography (1,514).§

Latin (1,416).

Physics (say 1,400).†

Chemistry (1,187).†

Botany (1,063).§

Music (767).

German (465).

Physiology and Hygiene (375).§

*See note * on page 177.

†See footnote ‡ on pages 177 and 178. Similar considerations apply to the figures for the Senior Locals, but the following additional notes may be useful:

English Language and Literature. - The numbers who took the separate divisions of this section were: (a) Composition, 7,130; (b) and (c) Books, 7,059; (d) and (e) Books + general paper, 5,100. No candidate could take both (b) and (c), or both (d) and (e).

Religious Knowledge. - This is the number who took either the Gospel or the Acts (+ Jewish students who took Kings). One of these two divisions, together with one of three others, was required for a pass in this section.

Drawing. - There are five subjects in this section in the Senior. The numbers in the separate subjects were: (a) Freehand, 4,268; (b) Model, 3,890; (c) Perspective, 119; (d) Design, 836; (e) Memory, 1,443. Candidates had to take two subjects to pass in the section and were not allowed to take more than one of (c), (d), (e). Supposing each candidate had taken only two subjects, the total number of candidates would have been about 5,300.

Mathematics. - The numbers in the separate subjects, of which there are six, and of which, in order to pass in the section, it is necessary to take both (a) and (b), were as follows: (a) Geometry, 4,487; (b) Algebra, 4,534 (as above); (c) Trigonometry, 1,376; (d) Analytical Geometry, 132; (e) Differential Calculus, 85; (f) Applied Mathematics, 310.

Physics. - The numbers in the four separate subjects, of which two were required for a pass, were: Experimental Mechanics, 308; Heat, 1,214; Sound and Light, 859; Electricity and Magnetism, 571. If each candidate took two subjects only, the total number of candidates would have been about 1,500.

Chemistry. - The separate figures were: (a) Theoretical, 1,187; (b) Practical, 1,076.

‡These subjects are all included in the one section, "History, Geography, etc." History is in three divisions - History of England, History of British Empire, Roman History. No candidate may take more than one of these three divisions.

§See footnote * on page 178.

[page 180]

Book-keeping (251)*

Logic (215)‡

Political Economy (171)‡

Greek (127)

Shorthand (61)*

Mensuration and Surveying (61)*

Spanish (44)

Agricultural Science (37)

Natural History of Animals (23)§

The total number of candidates 7,363. With one exception, all took Arithmetic (the compulsory subject). About 97 per cent took English; about 95 per cent took History; about 91 per cent, Geography; about 80 per cent, Religious Knowledge; about 70 per cent, French; about 68 per cent, Drawing (if the estimate be fairly accurate)†; about 62 per cent, Mathematics.

The total number of candidates who now take the Cambridge Examinations (i.e. 22,739 in 1909|| corresponds very closely to the number taking the Oxford ones, though the total is apportioned somewhat differently among the three examinations. Full statistics extending over a number of years are given on page 375. It will be sufficient here to mention that in the year 1909, 4,758 candidates took the Cambridge Preliminary, 9,950 took the Junior, and 8,031 took the Senior.

The age limits for candidates are the same as those for the Oxford Locals.¶

The results of the examinations are published with great fulness of detail. Separate lists for boy and girl candidates are issued in each case. Successful candidates are divided into five classes. The first three are Honours classes, the fourth includes candidates who are under 14, 16, and 19 years of age for the Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Local respectively, and the fifth includes over-age candidates. In all five cases the candidates are arranged in alphabetical order under the various centres. After the name of each candidate is added the name of his school (if any) and the name of the schoolmaster. In addition to these class-lists, information is published as to the distinctions earned in individual subjects by Junior candidates under 16 and Senior candidates under 19. In these lists the candidates are arranged in order of merit. Distinctions are also given in the Preliminary Local, but the names of candidates who obtain them are not published in a separate list.

*These subjects are contained in one section, in which each candidate must pass in Book-keeping, and one of the other two, of which only one may be taken.

†See footnote † on page 179.

‡See footnote ‡ on page 179.

§See footnote * on page 178.

||It is understood that this is the total number entered, and that not all of them actually attended the examinations.

¶But the age for Honours in the Junior Examination remains 16 in 1912 (see footnote † on page 166).

[page 181]

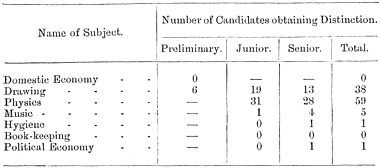

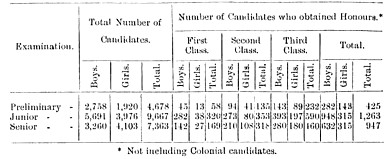

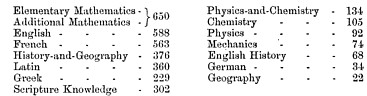

The following table shows the number of candidates who obtained Honours at the examinations in 1908:

The following table shows the number of candidates who obtained distinctions in the Preliminary, Junior, and Senior Local Examinations, 1908:

[page 182]

In addition to the Class Lists, supplementary lists are issued which show in detail the subjects which every candidate took, and those in which he failed or succeeded. Further, the Syndicate are prepared to give to the principals of schools information about the work of their pupils similar to that given by the Oxford Delegacy.

A list of the exemptions from other examinations which can be obtained by success in the Cambridge Local Examinations is given in Appendix D on pages 337 ff.

A few scholarships, prizes, and medals are awarded on the results of the Junior and Senior Local Examinations. St. John's College, Cambridge, gives two exhibitions of £30 a year for two years to candidates in the Senior Local, and the Trustees of the Reid Fund (Bedford College, London) give a scholarship of 30 guineas [1 guinea = £1.05] for three years to a girl candidate in the Senior Local. The Syndicate themselves give a scholarship of about £40 a year for three years, tenable at Cambridge. The Syndicate also give prizes, both in July and December, to the four candidates who stand highest in the First Class of the Senior and Junior boys and the Senior and Junior girls, £12 to each of the Seniors and £8 to each of the Juniors. The Royal Geographical Society offer four silver medals a year for success in Geography and Physical Geography combined.

(ii) The Cambridge Higher Local Examination

The Cambridge Higher Local Examinations are held twice a year, in June and December. The arrangements for centres and fees are generally similar to those of the Oxford Delegacy. Whereas, however, the Oxford Higher Local is open to candidates of any age, irrespective of their having passed any previous examination, the Cambridge Higher Local is only open to candidates who are either 17 years of age or have obtained an Oxford or Cambridge Senior Local Certificate, a Higher Certificate or the Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board, or a London Matriculation Certificate.

The subjects of the examination are -

Group R. Religious Knowledge.

Group A. English.

Group B. Languages (Latin, Greek, French, German. Italian).

Group C. Mathematics (Arithmetic, Geometry, Algebra, Plane Trigonometry, Conic Sections, Statics, Dynamics, Hydrostatics, Astronomy, Differential and Integral Calculus).

Group D. Logic. Psychology, Political Economy, History of Education.

Group E. Science (Elementary Chemistry and Physics, Chemistry, Physics, Botany, Zoology, Physiology, Geology).

Group F. Music.

Group G. Geography (Physical, Political, and Economic Geography, the History of Geography).

Group H. History (English History, general and special, European History, Greek History, Roman History).

[page 183]

The choice of subjects open to candidates is limited only by the following regulations. All candidates must satisfy the examiners in Group B or C. "For an Honours Certificate, a candidate either (a) must satisfy the Examiners in Elementary Arithmetic and in three of the Groups R, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and obtain a First or Second Class in two of the three groups required, or (b) having obtained Honours (i.e. a First, Second, or Third Class) in the Cambridge Local Examination for Seniors, or a Higher Certificate of the Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board with distinction in two subjects, must obtain a First or Second Class in two of the Groups R, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, provided that a candidate who presents a Higher Certificate of the Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board which does not include Elementary Mathematics shall also satisfy the Examiners in Arithmetic. For an Ordinary Certificate, a candidate must satisfy the Examiners in Elementary Arithmetic and in three of the groups R, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H. Certificates in the Cambridge Senior Local Examination and the Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board give no exemption from this rule."

As in the case of the Oxford Higher Local, the subjects required for a Certificate need not all be taken at one and the same examination.

The syllabuses in the various subjects of the examination are of an advanced order. It may be noted specially that there are more opportunities for practical examinations in Science than are offered by the Oxford Delegacy. In Chemistry a practical examination is (as in the Oxford Examination) obligatory where the accommodation of the centre allows it. In Botany, Zoology, and Geology candidates are required to describe and identify specimens. Further, in all subjects except Elementary Physics and Chemistry, there are practical laboratory examinations at Cambridge, which are open to all candidates who desire to take them, whether they take the rest of the examination at Cambridge or elsewhere. They are not compulsory, and success in them does not affect a student's place in the Class List in Group E, and is not required for the mark of distinction in the various subjects. But it secures a special mark in the Class List. In French and German an oral examination, at a limited number of centres, is on much the same footing as the voluntary practical examination in Science subjects. There is no practical examination in Music. Set books are not obligatory in any language, except to a small extent in Italian, but are optional in all.

The number of candidates who took the Cambridge Higher Local in 1908 was 1,041, and the number who qualified for certificates was 177.* Speaking generally, the candidates

*Excluding those who, although they passed in certain groups, did not complete their certificates, and those who had already gained a certificate and now added to their successes.

[page 184]

come from the higher Forms of girls' schools, and the examination is used mainly as an avenue to the University. It has this advantage, from their point of view, that it can be taken piecemeal, and that it includes no Greek. The examination, in fact, has in girls' schools very much the position of the Higher Certificate of the Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board in Public Schools for boys; but it is claimed that the Higher Local is a more difficult examination, except in Classics, to which, of course, less time is given in girls' schools than in the great Public Schools for boys.

As regards the standard of the examination, it is of a much higher character than the Senior Local, being, so we are informed, rather of the nature of a University Intermediate Examination, or even, in some subjects, of a Final Examination for a Degree.

(iii) "School" Examinations conducted by the Cambridge Syndicate

The Syndicate are prepared to examine schools, by means either of pure "School" examinations or by "School" examinations and Local examinations combined. The system is very similar to that of the Oxford Delegacy already described, and does not require separate description.

The number of schools examined by the Syndicate in 1909 was 76.

(iv) School Certificates and Army Leaving Certificates

The arrangements made by the Syndicate for granting Junior and Senior Certificates, and for Army Leaving Certificates, are practically identical with those of the Oxford Delegacy as regards both the subjects and method of the examination and the attendance qualification. No detailed description of them, therefore, is necessary here.

The number of candidates for School Certificates in 1908 was only 4, and in 1909 there were no entries at all; in 1910, however, 23 candidates entered for Junior, and 24 for Senior School Certificates, the numbers successful being 7 and 9 respectively.

(v) Inspection

Inspection of schools, as distinct from examination, was started by the Syndicate in 1882. As a matter of fact, the examination of schools, as conducted by the Syndicate, includes a good deal of inspection, and very few schools ask for inspection as apart from examination, especially now that the Board of Education undertakes inspection free of charge. The number of schools inspected by the Syndicate in 1905 was 3;

[page 185]

in 1906, 6; in 1907, 2; in 1908, 6; and in 1909, 7. The Syndicate conducted no inspections, pure and simple, in 1910. The fee charged by the Syndicate for inspection varies, of course, according to the size and curriculum of the school, the minimum fee being £5. If the inspection occupies one inspector for two days, or two inspectors one day, the fee is £8. These fees do not include travelling and hotel expenses.

(c) THE OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE SCHOOLS EXAMINATION BOARD

The Oxford and Cambridge Schools Examination Board, commonly known as the Joint Board, conducts several examinations, which may conveniently be grouped under three heads.

(1) Firstly, they conduct a "School" Examination, that is, an examination proper to an individual school, on which no certificates are given.

(2) Secondly, they conduct Higher and Lower Certificate Examinations. The examinations are held (a) at schools which desire that the papers shall form part of a "School Examination", and (b) "at Oxford, Cambridge, or such other centres as the Board may appoint". In practice, such centres are nearly always schools. The Higher Certificate Examination is intended for pupils of about 18 years of age, and the Lower for pupils of about 16.

(3) Thirdly, the Board hold an examination for "School Certificates", for pupils of about 17 years of age. Such examinations are, as a rule, held at inspected schools, and no candidates are eligible for certificates who have not been in attendance for three years. This School Certificate is accepted by the Army Council as an Army Leaving Certificate.*

The Certificate Examinations may be combined with "School Examinations", and the certificate papers may then be used by pupils who are not candidates for certificates. The Joint Board are prepared to accept the co-operation of the school staff in such portions of the examinations as are not used for obtaining certificates, Examinations for certificates are conducted entirely by the Board's examiners.

In all examinations, whether for certificates or not, the Board are prepared to grant alternative papers, either on different subjects or under different schedules, or to be set at different times, where the subjects or times presented do not suit the convenience of a particular school, provided that the additional expense so incurred is borne by the school.

(i) "School" Examinations conducted by the Joint Board

School Examinations held under the authority of the Joint Board may be held at any time of the year, and may include as

*But see footnote * on p. 173.

[page 186]

many or as few subjects and cover as many or as few classes as the school authorities choose. The examination follows the syllabus of the school, and as a rule allows the co-operation of the masters of the school in setting and marking the examination papers. An exception, however, is made in the case of the examination of the highest division of the school, when the examiners report on the general work of that division, and, if required, place the boys in order of merit, and award exhibitions, scholarships, and prizes. In such a case the examination is conducted exclusively by the Board's examiners, provided the statutes of the school permit.

The School Examination is conducted partly viva voce, except where the Board authorise the examiners to dispense with this mode of examination.

When the examination is over the School Examiners make a report upon it to the Joint Board, who afterwards send a report to the Governors and headmaster of the school.

The number of examiners required and the length of the examination is fixed in each case by the Joint Board after communication with the authorities of the school. The cost of the examination, including the expense of printing the papers and the salaries of the examiners, is settled on a fixed scale. An estimate is sent to the school before the arrangements of the examination are finally concluded.

The schools which utilise the School Examinations of the Joint Board are Secondary Schools which have a regularly constituted Governing Body, or which prepare a fair proportion of their boys for the Universities, or which in any other way give evidence of providing an education of the highest grade.

The manner in which the School Examinations of the Joint Board may be combined with the Higher or Lower Certificate Examinations, or the School Certificate Examination, will be described in the following sections.

The number of schools examined by the Joint Board in the year 1908-9 was 188, but this number includes all the schools at which examinations were held, whether the whole school, or select Forms, or only candidates for certificates were examined; it also includes two schools where the only examination was of a viva voce character. The number of pupils examined, who were not candidates for certificates, was about 5,600.

(ii) The Higher and Lower Certificate Examinations

(a) The Higher Certificate

The Higher Certificate Examination is held once a year in July at every school of which the authorities desire that the examination shall form part of a School Examination, and at Oxford, Cambridge, or such other centres as the Board may appoint. The examination is open both to boys and girls, but

[page 187]

the regulations differ somewhat for the two sexes. We will take the case of boys first.

Every candidate for a certificate must pay a fee of £2 on the first occasion. Candidates who have already obtained certificates are admitted to a subsequent examination upon payment of a fee of £1.10s. [£1.50]. Candidates who wish to obtain exemption from Responsions, the Previous Examination, and the London Matriculation Examination, although they do not obtain a Higher Certificate, pay an extra fee of 5s. [25p] to cover the expense of a special examination of their answers to ascertain if they have reached the necessary standard for exemption.

The subjects comprised in the Higher Certificate Examination are as follows:

Group I

(1) Latin.

(2) Greek.

(3) French.

(4) German.

(5) Spanish.

(6) Arabic.

Group II

(1) Elementary Mathematics.

(2) Additional Mathematics.

Group III

(1) Scripture Knowledge.

(2) English.

(3) History.

(4) Geography. |

Group IV

(1) Natural Philosophy (Mechanical Division).

(2) Natural Philosophy (Physical Division).

(3) Natural Philosophy (Chemical Division).

(4) Natural Philosophy (Experimental Science).

(5) Physical Geography and Elementary Geology.

(6) Biology. |

Candidates must, at one and the same examination,* satisfy the examiners in at least four subjects, which must as a rule be taken from not less than three different groups. They may not take more than six subjects (Elementary and Additional Mathematics being reckoned for this purpose as one).

The syllabuses of the various subjects are left very wide. The following points may be noted. Set books are not compulsory in Languages. Oral French and German are optional and are not necessary for a pass in either language. Success in the oral examination, however, is noted on the certificates of candidates who pass in the language as a whole, and, in and after 1912, no candidate will obtain distinction unless he satisfies the examiners in the oral test. The syllabus in English consists of Prose Composition and portions of authors to be specially prepared. The papers on the set books contain questions on Grammar, but the syllabus appears to give candidates no opportunity for obtaining credit for general reading except so far as it finds scope in the essay paper. In History, candidates have the option of taking periods of English, Roman, or Greek History. Geography may be taken as a separate subject, or as

*But see later as regards special provision for girls.

[page 188]

a composite subject combined with History. But even candidates who take History as a separate subject are required to have such a knowledge of geography as is necessary for the study of the selected period of History. There are practical examinations in Chemistry, Physics, and Mechanics. In Geology and Biology the examination includes the recognition of the principal fossil genera and the examination and description of an actual plant.

A school which takes the Higher Certificate Examination as part of a School examination may submit for the approval of the Joint Board alternative books or periods or special schedules, and may have special papers set on the basis of its own curriculum if the proposed alternatives are considered at least equivalent to those specified in the Board's syllabuses, and provided that the entire expense involved be defrayed by the school authorities.

The above description applies primarily to boys. The regulations for girls differ in the following respects: Girl candidates for Higher Certificates may take the examination in two portions, being required at each examination to satisfy the examiners in at least two subjects. The fee may be divided also between two examinations. Candidates who satisfy the examiners in two or more subjects receive a Letter stating the subjects in which they have passed. Those who desire to qualify for admission at Oxford to the University Examinations for the Degrees of Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Music, and Doctor of Music, although they do not obtain a Higher Certificate exempting them from Responsions, pay an additional fee of 5s [25p]. Further, Italian, Music, and Drawing, subjects not included in the boys' list of subjects, may be offered by girl candidates.

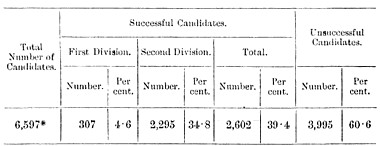

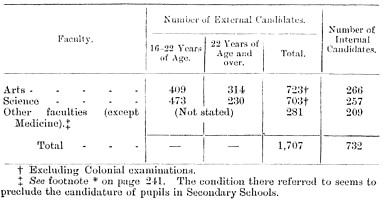

The number of candidates who are examined annually for Higher Certificates is considerable, the actual figures being 1,324 boys and 1,037 girls in 1909. Of the girls, 527 candidates were dividing their examination into two parts and were entering for the first part only.

The names of candidates who are successful in their examination are published in one Class List in alphabetical order, with letters showing the subjects in which they passed or obtained distinction. A separate list of all the candidates who obtained distinction in any subject is also published, also in alphabetical order, with letters to show the subjects in which the distinction was gained. In each list boys and girls are given separately, and in every case the name of their school is added. Supplementary tables are also issued, giving the subjects in which all candidates, whether successful or not in the whole examination, satisfied the examiners or obtained distinction.

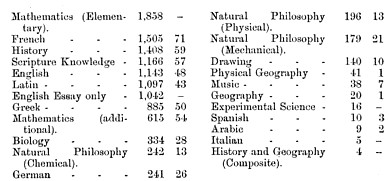

The Joint Board publish statistics showing the number of candidates who offered each subject of the Syllabus at the examination in any year. But, as many of the candidates divide their examination and offer only half their subjects at a time, it is not

[page 189]