[page 44]

CHAPTER IV

VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS

A. HOMEWORK IN JUNIOR TECHNICAL SCHOOLS

Some general considerations

Introductory - Junior Technical Schools have certain characteristics of their own which have a bearing on the problem of homework. They are designed to give a broad preparation for employment; the duration of the school course is either two or three years; the age range of the pupils is from 13 to 16; and the school week is usually longer than that in other types of schools, being normally about thirty hours.

In the course of this inquiry the conditions in fifty-seven Junior Technical Schools have been investigated. Forty-four of these schools are industrial in character, ten commercial, and three domestic. In all except two, regular and systematic homework is required as a normal complement of the instruction provided. In the remaining two schools a certain amount of work is, in fact, done at home, since pupils are expected to complete in their own time tasks which they have not finished in class.

The attitude of the parents - The evidence collected during the course of the inquiry shows that whilst there are a few isolated instances of excessive demands, in a great majority of Junior Technical Schools the demands made are reasonable and leave pupils some time to pursue interests of their own. Very few complaints from parents are recorded from these schools, and sometimes parents are reported as protesting that their children have too little homework. Nor is this attitude difficult to appreciate. Children are usually sent to Junior Technical Schools with the definite purpose of improving their chances of satisfactory employment. It is natural that parents should expect them to make the most of the opportunities that these schools afford, and find some assurance in witnessing for themselves obvious manifestations of the toil that they believe to be necessary to success.

Present homework requirements

Homework schedules - The amount of homework required is regulated in nearly all these schools by a time table, which is intended to secure a reasonable distribution of the pupil's time amongst the various subjects of the curriculum and to control the

[page 45]

total amount of time demanded. These timetables show that 1 hour and 1½ hours each night for five nights of the week are the amounts usually prescribed. Seventy per cent of the classes under review fall into these two groups and are divided almost equally between them. Of the remaining thirty per cent, about one half have a time allocation of less than 1 hour, and a half of more than 1½ hours. In view of the restricted age range in Junior Technical Schools it is usually considered unnecessary to differentiate between the different forms, but in a number of schools the amount of homework is increased as the pupils reach the highest forms. In most cases where more than 1½ hours is expected it is only in the top form that this heavier demand is made, and only in three schools does the demand exceed 2 hours.

The homework timetables provide, in general, for a fairly even distribution of homework throughout the school week. Only in five of the schools surveyed is it a recognised practice to give a heavier dose on Fridays, in view of the time available at the weekend. It is often found, however, that pupils do homework on Saturday or Sunday, not because there is too much to do on Friday evening, but because they prefer to have that evening free.

In a fair number of schools teachers are required to leave an interval of several days, and even a week, between the setting and the collection of homework, and this arrangement gives to the homework timetable a certain degree of flexibility of which the pupils are not slow to take advantage. A free evening is compensated by a longer period of work on another evening or at the weekend. There is, of course, the danger in this system that the pupil may leave too much to be done at one time, but this is likely to be reflected in the poor quality of his work and so to attract the disciplinary attentions of his teachers. On the other hand, there are substantial advantages to be gained not only from the opportunities which are afforded for the pupil to enter into social activities, but also from the exercise of his initiative and self control in disposing his time profitably. These advantages presuppose that the amount of homework given leave a reasonable margin of free time. The natural desire of the adolescent child for contact with other social organisations than the school is recognised in one or two instances by leaving one mid-week evening free from homework, whilst in several other schools the claims of homework are adjusted in favour of outdoor exercise, by reducing the amount required in the summer term.

Control of homework by head teachers - Although it is the normal practice for head teachers to lay down, in terms of hours,

[page 46]

the amount of homework to be demanded by his staff, few of them exercise any systematic continuous control over it. This does not mean that they have no regard to the homework that is done. Indeed, most head teachers scrutinise the pupils' homework from time to time in the normal course of their supervision. But such scrutiny is primarily directed to educational considerations; and rarely does machinery exist for checking the time that homework actually consumes. In a few schools, however, pupils are required to enter at the foot of their written homework, or on forms provided for the purpose, the amount of time spent on their several tasks, and in two or three instances these records are signed by the parents. In one school a strict supervision is maintained at the source, and teachers are required to submit each week to the head, details of the homework that they propose to set during the ensuing week. For the most part, however, it is left to the discretion of teachers, within the general framework of the timetable provided, to set their own homework in their own way.

Amount of homework actually done - With homework left so much in the hands of individual teachers, and of teachers who, in Junior Technical Schools, are mainly specialists responsible for only a part of the instruction given to any one class, it might be expected that there would be considerable variations from the homework schedule. Inquiries made from the pupils themselves go to show that in most schools the variations are not great and that they fall below the standard requirements almost as frequently as they rise above them. And slight increases over scheduled requirements do not prove onerous where, as is usual, these requirements normally leave pupils a substantial margin of free time. Only in six of the fifty-seven schools is there evidence of serious discrepancy between the standard laid down and the total amount of homework given, and it appears to be mainly in particular classes or on particular days that the excess is notable. The exceptions are so few that they can be very shortly detailed.

In one school the homework of the "A" forms amounts to about twice as much as the nominal quantity, but the nominal quantity is only six hours a week; and it is reported that, except in the first year Physics, the boys do not find the work really heavy. In another school, where the nominal requirement is from 7½ to 10 hours a week, the third form is given work that occupies 14 or 15 hours a week. In a third school one of the lower forms, which is supposed to have 5 hours a week for homework, is given work which occupies an average of 11¼

[page 47]

hours. A sample evening in still another school showed an average of about 2¼ hours as against a nominal demand of 1½ hours. In two other schools Friday night's assignments far exceed the nominal amounts and are a real burden on the pupils.

Why the normal time allowance is exceeded - Whilst there are very few instances of the homework demands as a whole being excessive, it is not infrequent to find that one or two subjects take up more than their allotted time. The "heavy" subjects vary from school to school and even from class to class, and it is clear that, in the main, the cause is to be traced to the individual teachers concerned, who either deliberately exercise a little extra pressure on their pupils or habitually underestimate the magnitude of the tasks they set.

There are two types of homework, however, which seem to be affected by a common tendency to exceed the normal time allowance: (i) Book-keeping and (ii) the subjects into which drawing enters, whether it be the sketching of apparatus in Science, or the illustration of note books in History, or the drawing of maps in Geography, or, as in two or three schools, the drawing of tools and other objects in connection with Woodwork. But it is generally agreed that the drawing, though it may take up additional time, is the least onerous kind of homework. Most pupils take a special interest in it, and often give more time to it than is strictly necessary for the purposes of their school work. To that extent their homework merges into a free leisure occupation which provides a healthy outlet for their creative impulses and, if it is free from inordinate pressure in other subjects, can have nothing but a wholesome influence on their development.

It is of interest to note that only in one school are essays mentioned as a source of overtime, and this is possibly because the essay does not play such a prominent part in the Junior Technical School as in the secondary school.

Even where the demands in individual subjects go beyond the nominal requirements, the evidence indicates that, generally speaking, they are not grossly excessive. And often they are counterbalanced by lighter demands in other subjects. The real danger arises when two comparatively heavy doses of homework fall on one night, and though such a coincidence appears to be rare, this happy result, in the absence of any systematic control, is fortuitous rather than deliberate. It is mainly due to the fact that the number of teachers who make excessive demands is comparatively small.

[page 48]

Individual variations as between pupil and pupil - The actual homework requirements in any class have been measured by the average time spent on such work by the members of that class. There are, of course, many individual variations: and this is inevitable under any system of setting homework to a whole class, in the form of tasks of a given magnitude. In some schools the variations are comparatively small: in others they cover a wide range, the slowest pupils needing two or three times as long as the quickest pupils to complete their work. Thus it may happen that demands which are reasonable for the majority of pupils may be excessive for a few individuals, and one of the problems which merits careful attention is that of easing the burden of homework for the slower pupil without at the same time increasing the gap between him and his quicker comrades. There is no evidence that this problem has been tackled in the Junior Technical Schools, but the investigations which have been made suggest two points which may have significance in this connection. The widest time variations appear to be found where (a) the tasks set for homework involve the breaking of new ground, or (b) homework is a carry-over of tasks not completed in school. On the other hand, homework time tends to vary within comparatively narrow limits where the work is mainly in the nature of recording subject matter, or of practising processes, which have been taught in class. The greater part of the homework in the schools examined is of these latter types.

Apart from differences in the capacity of individual pupils, some variation arises from the sex of the pupil. It is generally found in mixed Junior Commercial Schools that girls give rather more time to homework than boys.

The character of the homework in Junior Technical Schools - In all the schools where inquiries have been made, written homework, including drawing, predominates. It rarely falls below 75 per cent of the total and sometimes represents virtually the whole of the homework given. This practice rests mainly on tradition, and where definite reasons are adduced for it they are usually that written work provides objective evidence that homework has been done, or that written work is susceptible to numerical assessment and can, therefore, be taken into account in the terminal or annual appraisement of the pupils' work, or in one or two instances simply that head teachers and inspectors expect to see the pupils' homework.

The written homework falls into three main categories:

(i) making fair copies of notes taken in class, and expanding them;

[page 49]

(ii) exercises demanding mainly repetition of work taught in class: these may be either -

(a) practice in processes and operations,

(b) reproduction of subject matter;

(iii) exercises requiring original constructive effort -

(a) application of principles to new problems,

(b) essays, and exercises requiring reconstruction of subject matter.

The "learning" homework usually takes the form of either

(i) verbal memorising, e.g. passages of poetry, French conjugations; or

(ii) memorising the content of set portions of textbooks.

Most of the homework falls into the first two categories of written work, and its purpose may be said to be that of consolidating the results of the instruction given in class.

How homework is dealt with by the teachers

Correction by teachers in their own time - It is the usual practice for written homework to be corrected by the teachers, either in "free" periods which are allowed for this and other school purposes, or in the teachers' own time. In a majority of schools the process of correcting does not encroach seriously on the teachers' time out of school hours. This is due mainly to the fact that the amount of homework itself is kept within reasonable limits, but sometimes also partly to the fact that teachers are required to take evening classes and are thereby compelled to get most of their day school homework corrected in school. Where the volume of homework is above the average, however, a good deal of correcting often remains to be done out of school hours, especially by teachers of English subjects, who, generally speaking, get a heavier share of correcting than teachers of other subjects.

Class correction - In some schools it is customary to mark certain types of written homework in class, the pupils either marking their own work or that of their neighbours. Exercises requiring short, precise answers which are unambiguously right or wrong, lend themselves to this treatment: and it is mainly in Mathematics and, less frequently, Shorthand and French, that this method is adopted. It usually occupies only a few minutes of class time, and it has the advantage of reducing to a minimum the time lag between the working and the correction of the exercises. On the other hand, the mere information that an answer is wrong contributes little to the pupils' knowledge, and this method needs, therefore, to be supplemented by a more

[page 50]

adequate treatment. It is generally found that common mistakes disclosed by class marking are at once taken up by the teacher, and made the subject of further elucidation: and that the class-marked exercises are subsequently inspected by the teacher, either immediately or at intervals. This subsequent scrutiny is of great importance, not so much as a means of checking the original marking as for the purpose of watching the methods employed, the nature of the mistakes that are made, the style of the pupils' work and, in Shorthand, for example, the quality of the outlines.

Correction by teachers in class - Class time is used occasionally for homework correcting of a different type and one that has little justification. The teacher corrects the homework of each pupil in turn, while the class carries out independently some allotted task. It may be claimed for this method that it affords opportunity to deal in the most effective manner with each pupil's mistakes. But it tends to lead to the practice of setting long exercises in class mainly to keep pupils occupied, and this at the expense of class teaching. It involves a waste of time in explaining individually to a number of different pupils common difficulties that could be elucidated as effectively and more economically to the class as a whole. The class work that the pupils may be doing suffers from arbitrary interruptions. The discussion of homework mistakes with individual pupils is, of course, a valuable part of teaching and essential to the proper fulfilment of the purpose of homework, and it is quite appropriate that for this purpose advantage should be taken of opportunities which arise in the normal course of class activities. But this implies that the homework should have been previously examined by the teacher, that common errors should be treated collectively, and that only the residuum of "personal" difficulties should be reserved for the more extravagant method of individual tuition.

Testing of "learning" homework - Homework that consists of learning or memorising is almost invariably tested subsequently in class. In some instances verbal memorising is tested orally, but a written test is the normal method employed for the greater part of that homework which does not itself bear objective evidence of performance. The test usually occupies not more than ten minutes or so of the class time and often consists of a series of short questions which can be answered by single words, or phrases, or by numbers. This technique has undoubted value, but its limitations are not always appreciated. Though it may test satisfactorily a knowledge of facts and of words, it does

[page 51]

not necessarily test the pupils' comprehension of the subject to which the facts relate. The type of questions and answers on which pupils know they are to be judged, tends to direct their reading too narrowly to the accumulation of crude information. This method of testing, then, needs to be supplemented by others, designed to probe thoroughly the understanding of relationships and ideas, and which will serve to correct the balance between mere information and a fuller knowledge.

Undue importance attached to giving "marks" for homework - The tradition that the results of homework must always be assessed and given a mark lies at the root of a good deal of current practice in the schools: and in some cases the "marking" overshadows the correcting, or the correcting is concerned with computable errors rather than with ascertaining and supplying deficiencies in the pupils' knowledge and technique. It is also responsible for determining, in a large measure, the type of homework set, and for the fact that rarely are pupils given tasks that cannot readily be assessed. If more thought were given to the part that homework can play in the educational process, and particularly in the process of transforming the pupil into an independent student - if it were envisaged as an opportunity of enlarging the scope of education and of linking the restricted activities of school with the resources of knowledge available in the world outside - it would then be seen that a greater variety of tasks could be found, greater freedom in their performance could be given, and a certain amount of routine correction could be eliminated, to the benefit of pupils and teachers alike.

Facilities for homework

Special facilities at school not required - In the Junior Technical Schools surveyed homework is almost invariably done at home. In two schools only is provision made for doing homework in school. In one of these it amounts to nothing more than the reservation of a quiet room during the lunch period for pupils who take their mid-day meal at school: at the other a daily period of about 45 minutes is given to "preparation", during which pupils are expected to do about a half of the homework set, leaving the remaining half to be completed at home.

There is very little evidence of homework being seriously affected by poor home conditions. In one or two schools teachers are evidently aware of and take account of the difficulties experienced by individual pupils, but it seems to be generally agreed that, for the most part, reasonable opportunities for homework can be found. The fact that the parents have

[page 52]

elected to send their children to these schools when they were approaching the age at which they might have become wage earners, and the fact that the amount of homework given is usually not such as to occupy the whole evening, have both no doubt a bearing on this question, and tend to make it easier to secure reasonable conditions. In any case, there appears to be no widely felt need to provide special homework facilities in school.

The provision of such facilities in Junior Technical Schools would, in most cases, present serious difficulties, if it were not to be made at the expense of the existing curriculum. The school day is already rather long, the school building is often used for evening classes, and the teachers are often engaged in evening teaching.

Some comments and criticisms relating to the types of homework set

Pupils' notes of lessons - The copying of notes is one of the commonest forms of homework, and two advantages are claimed for it: first, that it helps to impress on the pupils' minds the matter with which it is concerned; and secondly that it provides neat and ordered statements in a form readily available for subsequent reference. From the point of view of the demands which homework makes on the pupils' energies, it is the easiest of the various types of homework. Nevertheless there is reason to believe that the desired results could be obtained just as well, and perhaps more effectively, with a smaller expenditure of time than is customary in many schools, if the real purpose of notes were kept clearly in mind, and they were not allowed to degenerate into school exercises designed for the aesthetic satisfaction of teachers and inspectors. It is unnecessary for notes to become replicas of textbooks, or to be treated as exercises in literary composition, or even to take the form of continuous narrative; or for illustrations to reach the high standard of draughtsmanship properly required in the drawing class. Indeed, the value of note books would be considerably enhanced, both intrinsically and as a medium of training, if pupils were taught to grasp the essential points of a lesson, to record them as far as possible by single significant words and short phrases, and to arrange them systematically in a manner that would suggest connections and would present, as it were, a bird's eye view of the ground that had been surveyed.

Independent practice based on classwork - Little need be said here of another type of written homework which, with the copying of notes, occupies the greater part of the homework time. Practice is necessary to gain facility in any operation,

[page 53]

and in such subjects as Mathematics and Shorthand it can appropriately be carried out in the pupils' own time, leaving class time free for work which requires the skilled attention of the teacher. It is only desirable to remember that frequency of practice is more important than its long duration, and that each dose of practice homework need only be small.

The value of working independent exercises based on classwork is generally recognised, and this form of homework is peculiarly adapted to such subjects as Mathematics and Bookkeeping. It is often used also in Science, History, and Geography. If the subject matter has been well taught in class, there is little danger of the homework making excessive demands. It serves to increase the pupils' familiarity with the subject or his facility of manipulation, and it discloses both to teachers and to the pupils themselves any lack of comprehension that has escaped detection in class.

Essays - Essays do not generally occupy a large place in the homework of the schools under review. In several schools, indeed, they are written only in class hours. In others it is customary for essays to be started in class and only completed at home. Of one school only, a Junior Commercial School, it is reported that this type of homework makes excessive demands on the pupils' time. Variations in the time taken to complete a given piece of homework may be greater in essay work than in any other subject. The range of these variations depends largely on the nature of the topics set, and the preparation which the teacher makes in class. That this inquiry has not disclosed serious variations in these schools may well be associated with the fact that essays on abstract topics are rarely found, and that directly or indirectly the ground is usually prepared in school for the essays which may be set as homework.

Verbal memorising - There is very little verbal memorising given as homework outside the realm of foreign languages, which are a normal feature of the curriculum only in Junior Technical Schools of the commercial type. The learning of a foreign language involves a good deal of memorising and in a course which extends over only two or, in some cases, three years, it is inevitable that pupils should supplement their class-work by work at home, if reasonable progress in the language is to be made.

Study of a textbook - Close study of a textbook again is not a common form of homework, and it occurs most frequently in such subjects as History and Geography. This kind of homework deserves more attention, for it has an important bearing on the

[page 54]

problem of training students. The reports available do not suggest that teachers look for more than a body of information as the result of their pupils' efforts: and experience shows that a good deal of effort may be wasted in unsystematic study. Considerable economy of time and energy could be effected in the long run, and pupils could be given greater power in the use of books, if a little time were spent in class in training pupils in efficient methods of study, and if the homework were directed to developing these methods rather than to the accumulation of a fixed quantity of information.

Some types of "informal" homework deserving of encouragement - There are occasional examples of homework of a less formal and rigid type than those already described, where no definite amount can be prescribed and a good deal of latitude is given to pupils. The culling from newspapers and other sources of information relating to specified topics, reading outside the range of school books, looking up references in public libraries, collecting information for debates, searching for and copying illustrations - these are types of informal homework that are met with, and invariably they appear to evoke a keen response from pupils and to stimulate their interest. They are hardly looked upon as homework, and though the time devoted to them often exceeds the standard homework requirements it is given voluntarily and with evident enjoyment. One of the valuable features of work of this type is that it helps to break down the barrier between school and the larger world outside, between school work and the free activities of leisure time. It is not every subject that offers opportunities for such activities, but they could appropriately be introduced more extensively than they are, and their introduction would be beneficial not only in its effect on the development of the pupils but also in its effect on the life of the school as a whole.

B. HOMEWORK IN PART-TIME COURSES

The present position

Homework generally recognised as an integral part of the students' work - Over the country as a whole homework may be said to be a normal requirement of part-time courses. Exceptions to this general rule exist, but they are not numerous and most of them refer only to certain types of courses. Thus in several areas little or no homework is demanded in Junior Evening Institutes, but this is usually when these Institutes form no part of an organised system of technical education. Again, in classes of a recreative or general cultural character,

[page 55]

and in practical workshop courses and domestic courses, homework is often not required. But of only one large and well populated area is it reported in more general terms that "no homework is set in a great many - perhaps a majority - of the junior and senior classes". As far as organised technical education is concerned, and this represents the bulk and certainly the more stable body of part-time courses, homework is generally recognised as an integral element of the students' work. It is indeed an essential feature of all National Certificate courses, the requirements for which now dominate the greater part of the field of technical education: and the need for homework is patent to teachers and students alike in courses which are designed to prepare for professional and quasi-professional examinations.

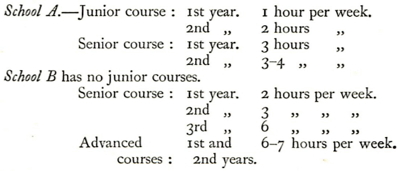

The amount of homework set - The amount of homework given in these courses is not commonly subject to the control of time schedules, as it is in full-time day schools. Teachers discover by experience what they can reasonably expect and adjust their demands accordingly. It follows that there is a good deal of variation in practice, but this is more pronounced where there is no definite objective marked by an examination. For the most part, the standards set by external or assessed examinations impose a limit below which homework cannot safely be reduced. But the tendency of teachers to demand what they can get leads in some senior and in most advanced courses to the setting of tasks which far exceed this limit. The amount of homework, then, varies not so much from school to school as from stage to stage. In the lower stages the demands are comparatively light and they increase progressively as the standard of the work advances. Two returns which may be taken as typical of the amount of time normally required for homework will make this clear. The junior courses referred to are designed for students between the ages of 14 and 16, the senior courses for students between the ages of 16 and 19 or 20, and the advanced courses for still older students.

[page 56]

The third year of the senior course is the final year of the ordinary National Certificate course, and many of the weaker and less persistent students have already dropped out before this stage is reached. The advanced course represents a still finer selection of students, whose toughness of fibre and seriousness of purpose have stood prolonged and rigorous test, and whose readiness to respond to the demands made upon them offers scope for pressing those demands to a point where they become a very serious burden.

Factors which tend to restrict the amount of homework - In estimating the significance of the figures given above it is necessary to remember that the courses to which they apply occupy already three evenings a week during the winter session, and this in itself makes a serious inroad on the leisure time of students who are working all day in factories and offices. Even in the earlier stages their homework demands the sacrifice of little less than a further evening's leisure, whilst in the highest stages it absorbs the greater part of their spare time.

It is not to be supposed, however, that every student does every week the full amount of homework that it set. It is not possible, under a system of voluntary evening classes, to insist upon homework with the same rigidity that is applied in day schools. In most classes it is found, that, whilst a certain number of students do homework with great regularity, others do it only intermittently and a few hardly at all. The proportion of those who do it regularly is often affected by the personal influence of teachers, but in general it is found to be lowest in the junior classes and highest in advanced courses. It is usually the best students who give most time to homework, and the less able students who neglect it. The latter rarely survive the earlier years of a senior course, and by the time that the third year is reached, and still more beyond that, in advanced courses, the character and quality of the students ensure a high percentage of regular and consistent homework. Then the omissions are mainly clue to causes over which the students have no control, and most frequently to the demands of employers for overtime.

The smaller proportion of homework found in junior courses may be attributed to two main causes: first, that the classes contain a more heterogeneous group of students, many of whom have no clear objective to give meaning and purpose to their work; and second, that most of the students have not, from the very fact of their age, yet formed the habit of voluntary, independent work: resistances both of mind and often of environment have to be overcome. Yet over a large part of the country homework has become a well-established practice in

[page 57]

junior courses, and it is common to find that the weekly tally maintains a steady average of 50 per cent and more of the total possible contributions. The influence of teachers on their students plays a great part at this stage, and accounts for many of the variations that are found. Some teachers succeed in getting homework from a very high proportion of their students whilst a few find difficulty in getting any at all.

That homework is often a serious burden to evening students is generally recognised, and in several schools means have been devised to lighten it. Homework in anyone week is restricted to one or two subjects according to a rota, each subject being allotted a homework period once in two or in three weeks. There is no suggestion that the standard of work suffers under this system.

The type of homework set - The homework set in part-time courses is almost invariably written work or drawing. It consists mainly of exercises based on the instruction already given in class, and the laborious copying of notes, though still found as a form of homework in some schools, is much less common than formerly. It is taken for granted, especially in the higher courses, that students will read their textbooks at home; but the time needed for this is often forgotten in determining the amount of written work.

Summary and suggestions

The influence of external examinations - The position of homework in part-time courses and technical education for students aged 16 or 17 and upwards has been deliberately established in recent years. And it is desirable to examine the bases on which current practice has been built up and to reach a clearer conception of the place of homework in this department of education. The bulk of part-time education, at any rate that in which the problem of homework assumes importance, is vocational in purpose and in character. It is designed partly to give knowledge and skill which is of direct utility and partly to provide a broad scientific basis for the understanding of technical processes or of commercial activities. For many students it leads to some recognised qualification which may help them to attain higher or more stable positions in industry or commerce. Examinations, therefore, play an important part in this branch of education, and most part-time technical courses are now largely determined either by examinations which are controlled by professional bodies, sometimes, as in National Certificates, in association with the Board of Education, or by examinations which are conducted by examining bodies of repute whose certificates are widely recognised.

[page 58]

Under the influence of these examinations there has been a general development of part-time courses which demand not the study of one subject only, but the study of a group of related subjects. These grouped courses are normally organised on a basis of attendance at classes on three evenings a week from September to April or the end of March. In each subject of the course students normally receive only one lesson a week: and if substantial progress is to be made the instruction then received must be consolidated by private study. Moreover, to develop the habit and the power of independent inquiry and thought is one of the main ends to which the training should be directed. For the serious part-time student, then, homework is essential.

Part-time evening students have little time for recreation and social activities - Though three evenings a week is but a meagre allowance of time for the study of any branch of technology with its ancillary subjects, it constitutes a large part of the leisure time of students who are already working all day for their livelihood. The amount of time that remains for homework, for recreation and for all the other demands of social life is not considerable: and homework cannot claim it all. The present inquiry has shown that, whilst over the greater part of the field of technical education homework requirements are limited to the equivalent of one or two additional evening's work, in some of the senior and advanced courses they amount to much more than this, and in some cases leave very little time for any other activities. There will always be keen students who will devote practically all their spare time to study whatever the amount of homework that is actually set. For courses attended by older students it is not necessary to prescribe strictly and in detail the amount that should be set. But it is desirable at all times to have machinery for co-ordinating the demands made by the different teachers of a course, and to relate their total requirements to a standard which leaves a reasonable margin of time for physical and social recreation.

The need for a more rational system - Under the most favourable conditions, however, it has to be admitted that the pursuit of a technical education in the students' spare time involves a sacrifice of leisure that seriously restricts the possibilities not merely of legitimate recreation but also of development in other directions. Nor is evening study at the end of a full day's work a really efficient method of acquiring a technical education. For most people it is the only method available at present, and it is necessary to make the best of it with all its limitations and its

[page 59]

drawbacks. But both the interests of efficiency and the legitimate claims of young people to a fuller life point to the desirability of a more rational system, which will permit the greater part of the instruction to be given in the day time. The need for this is already recognised by a number of employers, who release apprentices and other junior employees for a day or a half-day a week to enable them to attend day classes. The full contribution of technical education to industry is largely bound up with the extension of this enlightened practice.

The fact that homework inevitably demands a real and often considerable sacrifice of leisure makes it all the more important to use it to the best advantage. A good deal of thought needs yet to be given to the kinds of activity which can most appropriately and economically be pursued at home, and to the purposes which different types of homework can properly serve. Too often the nature of the task that is set is determined by custom and tradition, and by tradition that grew up in circumstances very different from those now obtaining in technical schools. Every piece of homework should be given with a definite and well-considered purpose.

Too much time spent at home in copying notes made in class - Without attempting to discuss all the problems that the thoughtful teacher will meet in planning the homework of his students, it may be useful to offer a few observations on some of the more important of them. In the first place, it seems clear that a certain amount of the written homework often set is of little educational value, and certainly does not justify the time spent on it. Such is the copying of notes, and such are the questions which require nothing more than a repetition of notes written in class. It may be quite appropriate for homework time to be used for making notes on class work; for example, where the exigencies of experiment in the laboratory or of practical training in the workshop leave little opportunity for making adequate notes at the time. The process of recalling what has been done, of turning it over in the mind, and of arranging it all in ordered sequence, has considerable value in establishing the knowledge more firmly in the students' mind and leading to a fuller understanding. Of a very different order is the work involved in making a fair copy of notes already taken down in class, elaborating them and even illustrating them with careful drawings. These are tasks which consume valuable time while calling for little mental activity; and they reach the point of absurdity when the note books become, as sometimes they do, virtual replicas of textbooks which the students have already bought.

[page 60]

The purpose of notes is not sufficiently understood. In the form which they frequently take, and which some teachers actually require, they lose much of their value through over-elaboration, and overloading with detail, and the essential points are obscured by the unnecessary verbiage of continuous description. A little thought given to the true purpose of notes and a little time spent, in the early stages, in training students in a suitable technique would, in the long run, lead to more effective notes, and to a saving of valuable time.

Inadequate preparation of the teacher leads to an excessive expenditure of time on some forms of written homework - Of the other types of written homework, the two commonest are (a) exercises which provide practice in processes or operations taught in class, and (b) exercises which involve the application to new problems of principles taught in class. Both types of exercises play an important part in education; and both require some independent work on the part of the student and are suitable for homework. In each case the effectiveness of students' efforts depends largely on the thoroughness with which the ground has been prepared by the teacher in class; and, in the second type of exercise especially, inadequate preparation leads to an excessive expenditure of time on a given task, often enough to no purpose. Adequate preparation is primarily a matter of efficient teaching and, as such, does not enter into this inquiry. But it is perhaps not irrelevant to suggest that exposition should be interwoven with exercises worked by the class under careful supervision, not only that students may lay firmer hold of the subject, but also that teachers may discover and correct errors and explain points which have been imperfectly understood. The adoption of this procedure, and the elucidation of difficulties that it implies, would often save a good deal of the students' time at home, and increase the effectiveness of their independent labours. It might then be possible to set fewer exercises for homework, though keen students would, no doubt, voluntarily exceed the minimum requirements. The essay type of exercise needs equally careful preparation. The planning of the essay and the marshalling of ideas are usually more important and provide more valuable training than the actual writing. They should undoubtedly be the result of the students' own efforts. It is in these early stages, however, that the teacher can be of greatest use; and it is, therefore, appropriate that the preliminary planning should be done in class where it can be discussed with the teacher. Or if this part of the work is done at home it is often enough to require only an outline to be brought to school, and not a complete essay.

[page 61]

More reading and less writing should be done at home by part-time students - The overwhelming predominance of written homework can hardly be justified by educational considerations, and the claims of study which is based on reading rather than on writing merit wider recognition. The reading of textbooks and, in more advanced courses, of technical journals, the consultation of works of reference, and the prosecution of inquiries, these are all activities which have a considerable value in the training of students. They possess this merit, which most written homework lacks, that they are types of activities which, if developed, may reasonably be expected to continue beyond the termination of a student's formal education. If written homework claims so much of the students' time that these other activities are impossible the ultimate effect will be harmful. It is unreasonable to take for granted that students will read seriously of their own accord, if no account is taken of the time that such reading demands, when determining the amount of written homework that is set. Reading and learning, and visiting public libraries for the purpose, should have a recognised place in every homework scheme.

The relation between classwork and the homework set requires to be determined in every case - The main difficulty in the way of such self-instruction is that most students do not know how to read profitably. This in itself is a further reason for making reading a definite part of the homework scheme. But it is also a reason for giving time in class to developing an effective and economical technique of study. Again, training in class should prepare the way for independent study outside.

It will be clear from what has been said that the relation between classwork and homework needs much more careful consideration than has hitherto been given to it. This relation will not be identical in all subjects, or in one subject at all times; and each teacher is called upon to think out his own problem. In some instances homework may well be used to prepare the ground for independent study, and subsequently to elucidate, correct and enlarge the results of such study. It will not always be possible to assess numerically the results of homework, nor is this necessarily to be deplored. The educational purpose is what matters: the part that each task plays in the whole scheme of instruction. When this is fully understood, homework will be characterised by greater variety, the students' time will not be wasted on mere routine tasks, or on tasks that are too difficult, and the formal homework demanded will leave some time for the freer activities of the mind that ultimately mean so much to the intellectual development of the student.

[page 62]

CHAPTER V

GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

General

The inquiry carried out in three separate types of school - elementary, secondary and technical - has revealed some difference among the three types in their views, and their practice, of homework. Such difference is natural. The work of each type of School is directed to a different objective. Conditions in each type are different. The age-range of the pupils is not the same: the school hours are not the same: the principle of attendance - compulsory, voluntary, whole-time, part-time - differs among the three.

These differences are reflected - as they are bound to be where facts are under review - in the accounts given in the preceding three chapters. They serve to explain what might otherwise seem inconsistency of practice between one type of school and another. They explain also, to a large extent, why different aspects of homework are emphasised in the different chapters. One instance may suffice. In the chapters on secondary and technical schools the point is at least implied that these are schools with a special aim, implying a standard of attainment: and homework - apart from any question of its possible excess - is on this ground represented as forming an accepted part of the school process.

In the chapter on elementary schools this emphasis on attainment is not found. The elementary schools, with some five million children of all degrees of capacity to educate, cannot usefully direct their teaching to one type, or one standard, of attainment. They have, in fact, had experience of that attempt: and the effects of the system of payment by results are hardly yet forgotten. The emphasis in this chapter is rather on the need for variety of activity to suit variety of capacity: the out-of-school activities described in the chapter - interesting alternatives to homework - represent one attempt to meet that need.

More significant, however, than the differences in point of view are the points in which the question of homework touches common ground in all three types of school. In all three types it connotes - however it may be defended on other grounds - some degree of pressure. In all three types this pressure is apt to be felt most during years when for many reasons pressure is

[page 63]

least desirable - during childhood and during adolescence. That their school day should allow due time for leisure after work, for recreation and for fresh air, without shortening the proper hours of sleep, is the need of all pupils in each type of school.

The fact that in many cases homework is so organised as to interfere with this need may by itself be held to justify this inquiry. The conclusion suggested as the result of the inquiry, that homework should be reduced, is based not only on physical needs for which the school course in each type of school must allow: it is based also on the educational consideration - which applies equally to all three types of school - that successful taskwork is not the only form of training, and that education is deeply concerned to develop qualities of resource, individuality and self-direction for which some leisure, and some experience of the independent management of leisure, are essential.

Elementary schools

The inquiry has shown that although homework is "voluntary", that is, although it is not part of the normal school course, it is in fact being done by many children, both seniors and juniors - and especially by juniors. Its incidence reflects the pressure of external competitive examinations and there is ground for believing that in recent years both this pressure and the amount of homework done by juniors, have increased.

There is no evidence that the increasing amount of homework set in the public elementary schools has been a natural development of the work done in the schools. Teachers have not, as a rule, imposed it as a means of consolidating what they have taught, nor is it defended on the ground that more ought to be taught in a day than can be taught in school hours. Recent developments in the curriculum of elementary schools, in laying more stress on physical and practical activity, have added variety and interest to school work. The inquiry gives no ground for thinking that these modifications and developments in the curriculum have so added to the burden of the school child that homework has become an inevitable extension of the day's labours. Nor do the reports suggest any ground for the opposite view, that homework in the "three Rs" is necessary because more school time is now given to practical activities. Indeed this view, which is not held in any responsible quarter, misses much of the significance of the practical work. The function of practical work in the school is not to oust the "three Rs" but, by the opportunities it gives of using them for real purposes, to help children to appreciate them.

[page 64]

It is clear from the inquiry that homework in the elementary schools, "voluntary" though it is, can, and not infrequently does, prove an excessive addition to school work for some children even of Junior School age.

The effect on the children, it may be said, is too little considered by the schools or the parents. Yet it appeared during the inquiry that many of the schools which set it are opposed to it: and many parents, to judge from correspondence in the press, deplore it though they ask for it. The truth is that the highly competitive nature of most examinations confronts both schools and parents with a dilemma. Either special efforts must be made - whether by means of homework, or coaching, or intensive work in school - to secure that their children are among the few who reach the standard of selection required by the examination; or the chances of success in the examination may be jeopardised.

For the schools themselves this issue is of capital importance. The choice it represents is the choice between framing their course of work themselves or having it framed for them from outside. The valuable developments in the way of recreative out-of-school activities in senior and other elementary schools - examples of which have been quoted - are the work of schools free to work out their own syllabus at their own pace, not tied to the syllabus of an examination, and it is significant that in schools where homework was being regularly set such leisure activities were seldom found. There was not time for them. Homework for examinations is proving an effective bar to the free development of education in the use of leisure.

Control of a practice which, though it is found to carry some obvious dangers for both children and schools is yet voluntary, cannot be easy. The real remedy, no doubt, is to lighten the pressure of examinations. This could be done in some degree by reducing the examination-value of special preparation in the subjects of examination. Experiments in the technique of examining, with this object in view, are at present being carried out, and it may prove possible to devise a method of selection for higher education which will lessen and perhaps abolish the value of cramming and of special coaching. A good deal of further experimental work, however, is still needed in this direction. The inquiry points clearly to some need in the meantime for more control of homework, as it is usually understood, viz. school lessons set to be done at home.

Tasks there must be, in the lives of children as in the lives of their elders: and every good school in its own practice recognises

[page 65]

this. But school homework is not the only, nor always perhaps the best, task for children at home; and they need leisure as well as tasks.

It is, therefore, recommended that no homework should be set to children under 12: if it is set to children in the elementary schools at all it should be limited to four nights a week. In amount it should not exceed one hour a night between the ages of 12 and 14, nor take more than 1½ hours a night after that.

Secondary schools

It is fitting to refer once more at the opening of this section of the Report to the inquiries which have been conducted and the resolutions which have been passed by the different Associations of Teachers in Secondary Schools.* Part of the evidence for the value of certain of the opinions and recommendations presently to be put forward lies in the fact that they are, broadly speaking, in harmony with those to which the Associations have already given expression. At this point in particular it may be remarked that the main lesson of the present inquiry has been anticipated in one sentence of the Memorandum of the Education Committee of the Association of Assistant Mistresses: "In the first place there is call for a much more definite idea of the educational ends to be achieved and the soundness of the methods used for their achievement in this more independent part of the pupils' work."

Perhaps on account of the special manner in which the present inquiry was conducted one feature of the situation with regard to homework came into greater prominence than in previous reports or memoranda on the subject, and that was the excessive demand which it makes upon certain children. In fact it is not an exaggeration to say that up and down the country there are a substantial number of children who suffer from a sense of oppression which makes itself most evident in their attitude towards this part of their work.

In order to guard against misunderstandings it is necessary to say explicitly that this is not a general charge against all schools. That it is not a charge against all teachers is evident from references made above to the resolutions and memoranda of their Associations.

From the account of the situation given in Chapter III it is easy to discern the main defects. They may be classified as follows:

(1) Insufficient control by the staff. Not all heads of schools have set up suitable machinery for an effective

*See Chapter III pages 25-28.

[page 66]

control. As a result, firstly, unsuitable tasks may be set for homework; secondly, the length of time required for any particular task is underestimated; thirdly, the total amount of time demanded is excessive.

(2) Faulty organisation. For example, a pupil for whom it would be profitable to complete the main school course in five years is only allowed four years.

(3) Failure to secure the co-operation of parents.

(4) Unsuitable home conditions.

The most drastic remedy which could be applied is obviously the total abolition of homework. Abolition has been tried in some schools and is supported in the press and elsewhere by those who claim that classwork in school takes sufficient toll of the child's energies. As against this it is held that the experiments in abolition are few in number and the evidence from them is inconclusive. Moreover, in the present state of our knowledge too much weight cannot be attached to arguments based on the fatigue of the children. No one has yet offered conclusive proof of so general a statement as that for the secondary pupil of normal health, strength and intelligence working under reasonably good conditions some twenty-five hours a week of schooling takes a full toll of his energies. Moreover, where fatigue is evident, it may be - and frequently is - attributable to other causes than homework, for instance, to an insufficient allowance of sleep. It must indeed be conceded that when to the twenty-five hours of schooling is added a long journey between home and school, the further addition of an hour or an hour and a half of homework may well make an excessive burden. Here special arrangements are called for. From some children in this category it might well be that no homework at all should be exacted.

The first argument here advanced for the retention of homework is not based upon educational grounds. The fact has to be faced that we live in a competitive world. In the competition for this or that economic advantage certain distinctions or hallmarks, so to call them, are of importance. The most obvious example of this is the possession of certificates of various kinds and the winning of scholarships. Even if examinations, certificates and scholarships were either modified or abolished, still the keener and better trained intelligence will - other things being equal - carry off the world's prizes. It is clearly established that for training the intelligence, homework, judiciously regulated, is a most powerful instrument.

[page 67]

The indisputable fact that many children, under the economic urge, are striving for distinctions which they cannot hope to gain for lack of the necessary ability, cannot be used as an argument against homework as such. The fault here lies on the side either of the head of the school, or of the parents, or of both, who have not been wise enough to restrain the child, or have wrongly gauged his ability, or have been carried away by ambition.

Arguments of a properly educational kind are not wanting - that is to say, arguments which rest upon a belief that the main function of education is to discover the best that is in the child and to help him to develop it. Perhaps the most important gain to be won from homework is the development of self-reliance and initiative, where the pupil is left to face unaided a problem suited to his abilities; or to follow up for himself a subject which appeals to his interests. Another gain, one of a more purely moral order, results from the pupil having to "settle down to his work" and resist distractions. All these advantages naturally accrue in a higher degree where the homework is done in home surroundings - it being postulated that the surroundings are in themselves not unsuitable - than at school under supervision, with the teacher close at hand to give help when called upon. A further advantage of home surroundings does not always appear to be appreciated. It is an aim of secondary education to help the pupil so to develop his interests and aptitudes that after leaving school he may be able, if he so wishes, to pursue this or that line of study by himself. Homework helps here: it accustoms the pupil to the idea that school surroundings are not the only ones in which he can work profitably.

Lastly it is not easy to see how a pupil can attain to anything which could properly be called mastery of this or that subject without independent or unsupervised study. It is not only that certain tasks such as the memorising of facts must be done by him alone, but that revision and consolidation are necessary parts of the process leading to the desired end.

It remains then to consider the changes necessary in order that homework may not be, as it now too often is, an unnecessarily heavy burden, and that the time given to it may yield the fullest advantage. To some extent the mere recital of the defects, given above, suggests the appropriate remedies. These fall under two heads - regulation and reduction.

Regulation must be based upon a clear understanding of the function of homework. It is clear that that function can only be properly discharged when the right kind of control is exercised by the staff. It falls to the head of the school to see that the

[page 68]

assistants collaborate loyally with each other and with him, and that, for example, the specialist or the strong-minded teacher does not annex more than his fair share of the time to be allowed. In large schools especially, form-masters or housemasters may have delegated to them some responsibility for seeing that the pupils are not overworked, and for helping to secure the help and understanding of parents. Subject-teachers are responsible for setting suitable tasks. It is here indeed that the most fruitful field of discussion will open out, since the technique, so to call it, of homework differs from subject to subject. Clearly no detailed consideration of the matter can be attempted here, but perhaps the following general points will give some useful guidance. First, the various kinds of task can be classified as follows: (a) Work designed to give the pupil such practice as may be necessary in particular processes or operations, or in the application to new problems of rules which have been dealt with in class. (b) Verbal memorising, as of poems, facts, principles or illustrative examples. (c) Revision of previous work. (d) Preparation for a coming lesson. Next, since, as has already been noted, the most important gain to be won from homework is the development of self-reliance and initiative, independent work must be fostered and excessive stress must not be allowed, as is now too often the case, to fall upon tasks designed solely to consolidate the instruction received in school. Incidentally it may be remarked that the excessive stress in this direction is due in many cases to the failure of teachers in their classroom practice to "drive the lesson home", for instance, by a few minutes of rapid questioning or a short spell of individual study. Thirdly, the bulk of the evidence of this, as of other inquiries, suggests that far too large a proportion of the homework time is occupied in writing. Those teachers who are parents know well how heavy the labour of writing may be.

In this matter of the regulation of homework the importance of securing the co-operation of parents can hardly be exaggerated. Co-operation here implies that parents will in a general way understand the main purpose of homework. It is true that at present most schools do invite parents to inform the Head Master or Head Mistress if a pupil is overburdened, but this safeguard is by no means complete. The parent may be diffident or may not understand, and frequently the pupil himself (or more often herself) prevents the parent from taking the obvious and necessary steps. There exist, then, a variety of subtle influences which prevent some parents from being quite frank with the head of the school or his assistants. It is the aim of the school to combat

[page 69]

these influences, and it is worthwhile to go to very great trouble to overcome them. In this Parents' Associations can be valuable allies, and where they exist their fullest co-operation should be secured.

Here it is in order to pass on to a hint which has already been given and may now be made more explicit, that careful consideration must be given to the home circumstances of the pupils. Two points in particular call for mention. Firstly, when the home is far distant, so that the pupil spends a long time in travelling to and from school, the homework to be attempted by him - if any - will differ not only in amount but sometimes too in character from that attempted by his classmates. If, indeed, the homework properly so called is abolished, then, wherever possible, time for independent (i.e. unaided) study may well be made in school hours. Secondly, such "homework at school" can profitably be arranged, but after school hours, for boys living not too far from school but in homes where the circumstances are unsuitable for homework. When this is done there should be an interval between lessons and homework with perhaps an opportunity for light refreshment.

The problems of regulation and of reduction are interdependent. On the one hand a more careful regulation will in many cases lead to a reduction in the amount of time prescribed for homework: on the other hand, a reduction in the amount of time would of itself in most schools compel a reconsideration of the nature and scope of homework. It is abundantly clear from this and other inquiries that in a considerable number of secondary schools the amount of time expected to be given is excessive. Nevertheless any pronouncement as to the right amount of time must be made cautiously and with due reservations.

For in the first place circumstances differ widely in different schools. Thus in boarding schools the problem of travel to and from school does not arise, and supervision of pupils is very much closer than in day schools, so that the danger that a pupil gives too much time to homework is materially lessened. In some day schools in thickly populated areas the journey to and from school is short, whereas in some country districts it may occupy two hours a day or more. Then again the length of the school day varies: some schools return 30 lesson-periods a week, others as many as 40. In some schools the main school course extends over four years, in others over five. Even if all the differences in external conditions were extinguished, there would remain the difference in capacity between one pupil and another.

[page 70]

All these reservations being borne in mind, it may be suggested that the following table affords some kind of guidance. It would most nearly apply in a day school in a thickly populated area in which the school hours amounted to 25 or 26 a week and the main school course was of five years.

(1) Preparation on not more than five nights a week: preferably on four nights only,

(2) Number of hours a night -

Up to 14 years of age, 1 hour.

Between 14 and 16 years, 1½ hours.

By comparison with the state of things known to exist in certain schools this very tentative suggestion may seem to involve a very drastic cut in the amount of time demanded. Nevertheless it does not represent a very great reduction in the time given to homework in some schools in which inquiries were made for the purposes of this Report, and it conforms fairly closely with recommendations contained in the resolutions of some of the Teachers' Associations. Something falls to be said as to the proposal that homework should be done on only four nights in the week. It is urged that no homework should be done on a Saturday.* The other free night might fall in the middle of the week. The time thus gained would give the pupil an opportunity of developing aesthetic pursuits, such as Art and Music, which not infrequently receive less attention than they deserve in school, and of playing a fuller part in the family and social life of the community. There is a very real danger lest children of secondary school age, spending their days at school and their evenings over homework should be brought up in an atmosphere of aloofness from much of the social life of their neighbourhood. Evidence of this danger is not wanting; in Wales, for instance, comment is made on the threat which arises from the excessive demands of the schools on their pupils, to the local culture, literary and musical, which has in the past been linked with church, chapel and other organisations. The training in citizenship is not all to be given in school and the practice of it should be largely exercised outside it. The danger that some abuse may be made of the new freedom is a danger to be faced whenever the bounds of freedom are enlarged. Further, those who argue that Satan finds mischief for idle hands to do may be

*The further restriction might be made "and still less on a Sunday", were it not that some parents may desire that the children should give up twenty minutes or half an hour to Scripture homework ("learning" not "written").

[page 71]

reminded that they are in effect pronouncing a serious indictment against both school and home.

Among other advantages which might be looked for from a reduction in the time required would be increased freshness and fitness in the pupils, and for the teachers a reduction in the often far too heavy burden of correction. Again, it is by no means beyond expectation that some children - especially the more intelligent and active - would in fact voluntarily, without the slightest suggestion from outside, extend their efforts beyond what was required on the timetable. Than this there could hardly be a better way of developing initiative.

One further matter deserves consideration which it appears all too rarely to receive - and that is the "holiday task". This institution has fallen into undeserved decay simply because it was not attended by due regard to the situation presented. The "task" nearly always consisted in reading a book not necessarily uninteresting in itself but to be read with an examination and all its attendant penalties in view. If the holiday task is to be revived - and in principle there is much to be said in its favour - the first step to be taken is to abolish the examination, the second to vary its nature to suit the individual's tastes and abilities. Books are not the only suitable material: the field must be extended to include such things as music, art, the various crafts, Natural History and possibly practical science or observations of an elementary kind and so on. If the task, whatever it is, involves some help from other members of the family, so much the better. Anything that will bring the older and the younger generation to work together and to find common interests and difficulties is to be welcomed.

This section of the Report opened with the suggestion that the problems of homework call for yet further investigation and for careful thought. Here it may be observed that those who are concerned with the training of teachers for secondary schools, especially in the University Training Departments, might well give to these problems - both generally and in particular relation to the several subjects of the curriculum - a prominent place in their scheme of training: furthermore, teachers who are working for a higher degree in Education could find in homework and in experiments in homework a theme capable of yielding fruitful results.

Technical schools

The picture in schools of the Junior Technical School type is brighter. Homework is set, but it does not constitute so excessively heavy a burden as in schools conducted under the

[page 72]

secondary school regulations. This is, at first sight, curious, for the time spent in school is longer. The explanation almost certainly lies in the freedom of these schools from external examinations with the uncertainties and fears which these engender. The aim of the pupils is to enter industry or commerce, and the fear of not securing a post is not present in the minds of pupils or of parents of pupils of reasonable industry. The only point of any importance is concerned with the kind of homework which is set. As is pointed out in Chapter IV, some teachers in these schools, as indeed in other types of schools also, do not exercise the wisest discretion in the type of work which they set. Some advice is given on the point in that chapter.

Older students, aged 16 upwards in senior institutes, are engaged in industry in the day time and they attend evening classes in order to fit themselves for more responsible posts. Their life is hard and those who survive the course, which invariably and necessarily includes home preparation, are individuals of tough fibre. That the road to success should be such heavy going is a matter which all generous-minded people must deplore. The remedy does not lie in any changes in the educational system but in the outlook of industry and of employers. Many employers do realise their obligations, and they assist the ambitious apprentice or workman by releasing him for part of the day time, a half or even a whole day. Successive Presidents of the Board of Education have often appealed to industry for extension of this practice and will doubtless continue to do so, till it becomes more general.

[page 73]

APPENDIX I

A

Dear Sir, or Madam,

Will you please answer the following questions, and return the form to school on or before MONDAY, 11th FEBRUARY, 1935?

(1) How much time (on an average night) does your boy spend on homework?

(2) Does this appear to you too much or too much too little? (about right 271; too much 119)

(3) Does homework prevent your boy indulging in his hobbies? (yes 117; no 273)

(4) How would your boy spend his time if there were no homework?

(5) Would you prefer homework on certain nights only, so that two or three nights a week might be free? (yes 228; no 162)

(6) Bearing in mind that homework is at present forced upon schools by outside competition and examination standards, do you think that your boy would be able to reach as high a standard if his evening work were planned by himself? (yes 42; no 348)

Any further remarks.

Signed _____________ (Parent or Guardian).

Name of Boy __________ Form ____

B

(1) Do you find that your son/daughter shows signs of fatigue as a result of school life? (Parents seem to be fairly evenly divided though a small majority of 44 to 38 answer in the negative.)

(2) Do you prefer evening preparation to be done at home or at school as it is done at present? (Only 22 out of 80 would prefer prep. to be done at home.)

[page 74]

(3) Is work brought home in the evenings, and how long is spent on it? (In Vths and above practically everyone takes work home. Time varies from ½ - 4 hours.)

(4) Do you consider there is too much preparation set? (Parents well divided. 44 to 37 do not.)

(5) Do you think the present holidays too long? (46 against 37 are quite satisfied with the present holidays.)

(6) Would you welcome an attempt to spread the year's work by (a) reducing working hours in term time and demanding some work in the holidays, or (b) by altering the school year to four shorter terms and four shorter holidays? (Strong opposition to reducing working hours in term time, but opinions as to four terms are fairly evenly divided.)

(7) Have you any suggestions for the improvement of school hours or organisation? (Free Saturdays was a popular suggestion. A number felt that there was too much spare time in the afternoons. Among other suggestions were some to the effect that the afternoon period should continue till 4.30, and then no more work at all.)

APPENDIX II

QUESTIONNAIRE

Boy's Name ________ Form ____

Has he tackled his homework with greater vigour and keenness? "Yes" (81 per cent).

Has he worried less about his homework? "Yes" (72 per cent).

Has he slept better as a result of reduced homework? "Yes" (62 per cent).

Has the reduction of homework had a beneficial effect on his physical health? "Yes" (73 per cent).

Has he in general devoted the extra time to worthwhile things, such as hobbies, reading, open-air recreation, etc. Or has he wasted it? "Yes" (95 per cent).

Would you regret a return to the former amount of homework? If not, please state your reasons, "Yes" (87 per cent).

[page 75]

APPENDIX III

Dear Sir (or Madam),

"No Prep." Experiment

Before the beginning of next term I am anxious to collect all available opinions in order to assess the results of the experiment and to decide on future arrangements in regard to school preparation. I hope that all parents without exception will be good enough to help me by answering the following questions to the best of their knowledge and ability, and by returning the replies to me before the end of August.

Name of boy __________

(1) Physical Health. Reply.

Has the absence of compulsory "prep" been -

(a) beneficial? Yes. 63 per cent.

(b) harmful? Yes. 2 per cent.

(c) without appreciable result? Yes. 35 per cent.

(2) The Use of Leisure.

Has the experiment led to the cultivation of -

(a) useful hobbies or interest? If so, please indicate. Yes. 43 per cent (sport) 29 per cent (cultural).

(b) hobbies or interests of doubtful value? If so, please indicate. Yes. 10 per cent (doubtful)

(c) unwise pursuits? Yes. 13 per cent (unwise).

(3) Future Policy.

Do you prefer -

(a) that the experiment should continue? For continuing, 25 per cent.

(b) that arrangements previously in force should be resumed? For reverting, 7 per cent.

(c) that "prep" should be carried on as before during the Winter terms, but not in the Summer? For no summer "prep", 33 per cent.

(d) that "prep" should be excused on Wednesdays and Saturdays, but not on other evenings, throughout the year? For no "prep" on half holidays, 35 per cent.

(4) Any other Observations

If there are any you wish to make, please add them in the space opposite, or in a covering letter.

[page 76]