[page 24]

Appendix 1

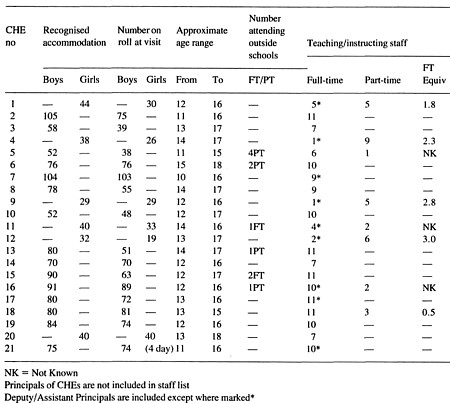

Table 1 Accommodation, pupils and staff

[page 25]

Table 2 Subjects stated to be in the curriculum

[page 26]

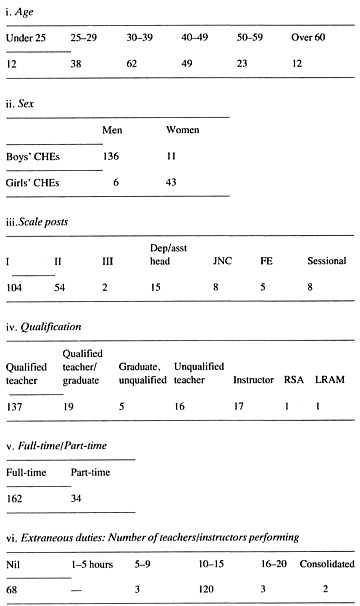

Table 3 Teaching staff

vii. Main previous experience

a. Teaching

| Primary teaching | 19 |

| Secondary teaching | 91 |

| Independent school teaching | 7 |

| Teaching in FE establishments | 5 |

| Teaching in other CHE establishments | 7 |

| Teaching in outdoor activities centre | 1 |

| Teaching in special school | 2 |

[page 27]

| Teaching in dance school | 1 |

| Supply teaching | 1 |

| Teaching overseas | 1 |

| Teaching in assessment centre | 3 |

| Teaching in remand home | 1 |

b. Other employment

| Nil | 42 |

| Child care | 1 |

| Borstal | 3 |

| Navy | 2 |

| RAF | 1 |

| Teacher training | 1 |

| None stated | 7 |

viii. Main subject of qualification

| Physical education | 33 |

| Woodwork | 16 |

| English | 15 |

| Mathematics | 12 |

| Geography | 10 |

| Home economics | 9 |

| Art | 8 |

| Painting/decorating | 8 |

| Building | 8 |

| History | 7 |

| Primary phase | 8 |

| Horticulture | 5 |

| Science | 7 |

| Sociology | 6 |

| Biology | 4 |

| Religious education | 5 |

| Drama | 4 |

| Typewriting | 4 |

| Music | 3 |

| Humanities | 3 |

| Special education | 2 |

| Zoology | 2 |

| Seamanship | 2 |

| Agriculture | 2 |

| Metal work/Engineering | 2 |

| Handicrafts | 2 |

| Remedial teaching | 1 |

| Dancing | 1 |

| Behavioural science | 1 |

| Classics | 1 |

| Catering | 1 |

| Economics | 1 |

| French | 1 |

| Philosophy | 1 |

| Draughtsmanship | 1 |

This is included to indicate the general trend of subject qualification: where second subjects were stated, these have not been included.

When, however, CHEs are compared in respect of ALL the subjects of qualification of their teachers/instructors, it is clear that some are much more favourably placed than others.

For example, one CHE had nine full-time teachers and instructors, of whom four

[page 28]

were qualified teachers, two were unqualified, and three were instructors. Their subjects of qualification were PE (3), Geography (2), History (1), Mathematics (1), Music (1), Religious Education (1), Rural Studies (1), Engineering (1), Woodwork (1). Technical Drawing (1), Brickwork/General Building (1).

By contrast, another CHE of about the same size had a staff of eleven full-time and three part-time teachers, all qualified, who combined expertise in the following subjects: English (4), Mathematics (2), General Subjects (3), History (1), Geography (3), French (1), Music (1), Sociology (1), PE (1), Woodwork (2). Craft (1). Rural Studies (1), Building (1), Painting and Decorating (1), Art (1), Domestic Science (1). In addition the Principal could offer Science and Maths.

ix. Subject recorded as first specialist subject being taught in present post

| General subjects | 49 |

| Physical education | 18 |

| Mathematics | 15 |

| Art | 14 |

| Remedial subjects | 14 |

| English | 11 |

| Woodwork | 10 |

| Building | 7 |

| Home economics | 7 |

| Horticulture | 7 |

| Science | 5 |

| Metal work/engineering | 4 |

| Typewriting | 4 |

| Painting/decorating | 4 |

| Religious education | 4 |

| No subject specified | 4 |

| Drama | 3 |

| Rural science | 3 |

| Social studies | 2 |

| Child care | 2 |

| Seamanship | 2 |

| Handicrafts | 2 |

| Dancing | 1 |

| Biology | 1 |

| Agriculture | 1 |

| Horsemastership | 1 |

| Geography | 1 |

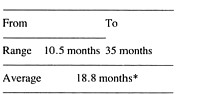

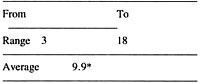

Table 4 Length of stay of pupils in CHE

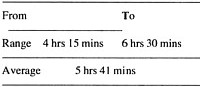

Table 5 Length of teaching day

[page 29]

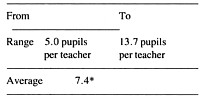

Table 6 Pupil teacher ratio

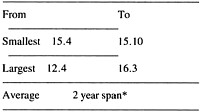

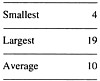

Table 7 Size of the teaching groups

Table 8 Age range of the teaching groups

Table 9 Number of sending authorities

These [Tables 7 and 8] operate together, so that, for example, a group was recorded of 15 pupils aged 12-15 years; another had 14 pupils aged 11-15 years. The group recorded in Table 7 as the largest consisted of 18 pupils aged 15-16 years. The group in Table 8 with the largest age range (12.4 to 16.3) varied in size between 5 and 14 pupils.

*Found by taking the unweighted arithmetic average of the individual averages for the 21 CHEs.

[page 30]

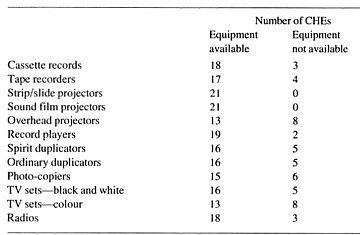

Table 10 Audio visual equipment

Most CHEs were in possession of a wide range of audio-visual equipment. In addition to the items mentioned below some CHEs reported that they had the use of video cassette recorders (mentioned 5 times), language masters, and photographic equipment.

In the 21 CHEs visited, the availability of equipment was stated to be as follows:

Table 11 Courses attended

Teachers were invited to complete anonymously a form recording their attendance at courses in the last five years. Of the 196 teachers and instructors, 140 did so. Thirty-four stated that they had attended no lectures or courses in the period.

Attendances recorded from the 140 returns

| One lecture only | 21 |

| Several lectures on separate days | 112 |

| Single whole-day course | 62 |

| More than one day, less than eleven | 70 |

| More than ten days, less than one term | 19 |

| One term or more | 40 |

Comments

More opportunities needed. (Many returns)

Easier secondment.

Better publicity for courses.

More school-based conferences.

More visits to other institutions.

More one-week courses.

More technical courses.

More child-care courses.

More time for study.

More opportunities to meet others.

Help in avoiding stagnation.

Suggestions for type of course

Courses on care and control.

Courses on remedial work.

Courses on counselling.

Courses on diagnostic testing.

Courses on health education.

Courses on curriculum development.

Courses on RE.

[page 31]

Quotations and notes from returns

"If it were not for my personal interest in the building trades I could just stagnate for the want of refresher courses and that is good for no-one".

"Try to make the Social Services who employ us aware of their responsibility towards financing our in-service training. We have a low priority - so low in fact that people tend to stop applying for courses after so many refusals [to second). The reason given for refusal is that teachers are already trained whereas care staff are often not".

In one CHE only three out of ten members of staff had attended any courses at all in the past five years and this was just a one-day course at the local College of Technology on 'Safety in the use of abrasive wheels'. All three attended the same course. Only two had any suggestions to make about future in-service courses:

i. a short intensive course on modem techniques of wood turning - to keep up to date with timber and machinery,

ii. any course to consider up to date methods of education.

[page 32]

Appendix 2 Timetables

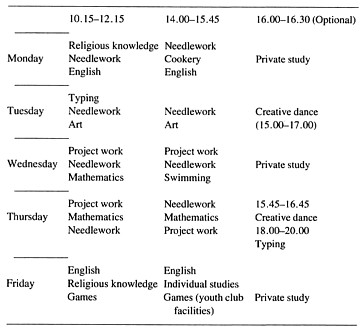

Girls' CHE Timetable

[page 33]

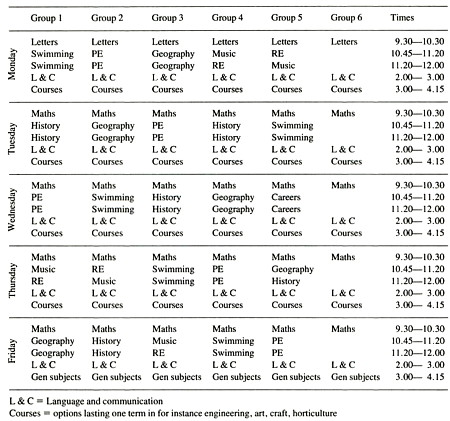

Boys' CHE Timetable

[page 34]

Appendix 3 Community homes with education - education management

Paper prepared by HMI to promote discussion which might assist in the preparation of a job specification.

Outline of possible responsibilities of a deputy head (education)

1. Identify the general learning needs of the young people admitted, in particular taking into account:

needs for remedial work to promote numeracy and literacy

preparation for return to a comprehensive school

preparation for leaving at 16+ to employment/unemployment

history of school attendance and performance

general social/educational needs, taking full account of personal background, including reasons for being in care.

2. Consider, with the head and deputy head (care) and in consultation with aJl the staff, how to ensure a unity of philosophy between the educational provision and the care provision and to promote a concerted approach to such matters as staff attitudes, relationships, control mechanisms, and sanctions, in order that the overall aims of the Community Home may be achieved.

3. Formulate, in partnership with the teaching staff, and in consultation with the care staff, a general curriculum relevant to the needs identified above, stating priorities. Such a curriculum should include:

language and communication skills, especially oral communication with peers and adults.

mathematics and science.

environmental and social studies.

creative activities - music, art, drama, etc.

moral and ethical studies - religious education, personal/social development.

practical skills - PE, craft, vocationally directed work.

Personal and social development are likely to be very important, in particular for older children, and will include preparation for adult responsibilities, health and careers education, and what are currently described as 'life and social skills'. These involve developing self-awareness through reflection, sensitivity to others and an increasing part in decision-taking.

4. Devise with the Deputy Head (care) a procedure for preparing a development programme for each individual child, integrating the contributions of the care and teaching staff. This will take account of the

[page 35]

curriculum areas in (3) in order that the care staff can help to consolidate the learning of the individual child in the classroom.

5. Establish with the teaching staff individualised learning approaches, allocating responsibility for reviewing each young person's educational progress, and provide a framework for analysing this progress in a way which can be used to determine future learning needs, which will be helpful to other teaching and care staff, and which will aid decision-taking and lead to future action.

These approaches will allow for induction/assessment; consolidation; and preparation for release.

6. Develop appropriate teaching approaches to interpret this overall curriculum and to provide learning opportunities in acceptable forms. For these children the method of teaching is probably more important than the content. Motivation through perceived relevance is a key factor, especially vocational relevance. Thus textbooks must be appropriate in terms of cultural background as well as reading age. Integrated studies and project work which maximises success are likely to be preferable to conventional subject approaches. English literature can provide a suitable starting point for exploring feelings and attitudes and for social studies, given the necessary teaching skills. A variety of teaching styles, including small group work, is required if the full range of learning needs is to be covered. Counselling skills are also appropriate, with opportunity to practise them.

7. Plan personal support and in-service training to assist the staff to develop the attitudes, skills and confidence necessary to use these methods. It is recognised that some staff require considerable help to develop the desirable range of teaching styles, and the ability to recognise when to relax 'control' structures. Such staff development requires considerable advisory input, making full use of LEA experience and resources, including teachers' centres and colleges of education. Full use should be made of staff experience for mutual support and training, including that of the care staff.

Access to a wide selection of teaching materials is essential (textbooks, learning kits, audio-visual aids) with professional advice as to their suitability for different children and different purposes.

8. Negotiate the teaching accommodation and other resources necessary to implement the desired programme, being aware of the importance of the total physical environment. This will include the utilisation of appropriate youth and community resources, eg Duke of Edinburgh's Award Scheme, to supplement the main educational provision.

9. Establish review procedures for the evaluation of individual progress, teaching methods and the 'hidden curriculum', with provision for continuous adjustment as necessary.

10. Provide such communication channels with the care side that the education provision is fully integrated with the total provision of the community home and designed to support the work of the care staff.

[page 36]

11. Ensure, as far as is possible, effective links with:

Observation and Assessment Centres, so as to be able to interpret their assessment of individuals.

Social Workers, and through them future schools/careers officers, as appropriate. It is necessary for the individual's educational achievement to· be described in a form understood by the recipient and appropriate as a basis for future action.

LEA advisers and teachers' centres, in order to make full use of relevant LEA experience, in particular with remedial and disruptive pupil units, and with special education.

This list may help in the identification of the personal skills required in educational management within the CHE, and in suggesting the action which should be taken to develop these skills.