[page 277]

CHAPTER XIII

HENRY VIII AND THE SCHOOLS

HENRY VIII was, perhaps, the most highly educated person for his time who ever sat on the throne of England. Whether Lord Herbert had any authority for saying that as a younger son Henry was originally destined for a clerical career and the throne of Canterbury, it is certain that he was educated like the most learned clerk. Under John Skelton, Bernard Andre, and others he received the best grammar school, song school, and university education of the day, in Latin, literature, rhetoric, dialectic, and music, besides knowing French, Italian, and Spanish. Hence it was that he became the excellent speaker and writer, the eminent theologian and the expert musician he is admitted to have been. Hence his zeal for learning and for education. No king ever showed more desire to promote learning and learned men, and none was more impressed and desirous of impressing on others the advantages, or did more for the advancement of education. Whether in the statutes of the realm or in the ordinances and statutes of the many foundations of his time, he was never tired of expatiating on the necessity of education and the benefit that educated men were to church and commonwealth.

The reign of Henry VIII has a far better title than that of his son to be regarded as an era of educational development, though it has no more title than the latter to be regarded as the starting-point of an entirely new system of schools or of any great educational advance. The notion that it was, seems to have been chiefly derived from Samuel Knight's Life of Colet, published in 1724, in which a most exaggerated account is given of Colet's supposed foundation, really only a re-endowment, of St. Paul's School. Colet's foundation is not really a product of Henry VIII's reign at all. He tells us

[page 278]

himself that he 'in the year A.D. 1508 began to edify in the East end of the churchyard of Paul's a schoolhouse of stone for children to be taught, free, to the number of 153'. The whole design was therefore made and its execution begun in the reign of Henry VII; though it is of course true that the endowment and legal foundation were given and completed in 1510 to 1512 under Henry VIII. But in everything he did in regard to the school, Colet followed, and did not set, a fashion. His new school he placed only a few yards northward of the old school, which as we saw was placed there about 1111. He obtained the royal licence in mortmain for a school in the Churchyard, 6 June, 1510, and on 27 July he, as Dean, with the Chapter granted William Lily, of Magdalen College, Oxford, then appointed first master of the 'New School of St. Pauls', all the privileges of the master of the old school, including a stall in the choir, and 'took him into their bosom'. On 28 March, 1511, he got the Chapter to join him in conveying to trustees for the new school, the old school, 'lately called Poules schole', and three shops underneath it, and on the same day the Chancellor of St. Paul's released to the same trustees all his rights over the old school; while the same day the Dean and Chapter conveyed to the same trustees the land on which the new school and master's house were built. Colet also asked the Pope for a transfer of all the rights and privileges of the old to the new school. In July, 1511, Colet granted a large amount of land in Buckinghamshire and some property in London, being his whole inherited patrimony, to the Mercers' Company, of which he was a member, for the 'continuation of a certain school in the cemetery of St. Paul's church'. On 10 June, 1512, the three trustees bargained and sold the two school buildings, the old and the new, to Colet, who the same day made his will giving them to the Mercers' Company, in trust for 'the newe scole at Poules'. On 17 June, 1512, he produced to the company his 'Boke of Ordinances of the Scole of Poules' under which they were to act as governors, and on 27 July the company took possession of the schools and the foundation was legally complete, or, as Colet puts it, he 'in the yere of our lord a thousand fyve hundreth and twelff, full accomplisshed and fynysshed the same scole and mansion in every poynt'. These first

[page 279]

statutes are not extant, having been superseded by a new edition on 18 June, 1518. The steps of this foundation have been particularized because the school was represented as an entirely new foundation, with no connexion with the old school, which was represented as having disappeared, whereas Colet himself told the Pope in asking for a Bull to place his new school in the position of the old one that the old one was going on 'though of no importance'. He was careful to place the new school exactly in the position of the old, except that the Mercers were substituted for the Dean and Chapter and the Chancellor of St. Paul's as governors. Nor was Colet, as was also represented, making a new departure in entrusting the school to a lay body of governors and that a city company, for, as we have seen, there had been a constant stream of schools with city companies as governors from 1443 at least.

A great deal has been made of the curriculum laid down in Colet's Statutes and particularly of the mention of Greek and the lay head master, as showing that Colet did initiate a new educational movement, if not a new system of schools. As for the lay head master, the novelty of that is sufficiently refuted by William Sevenoak's foundation at Sevenoaks in 1432, that the master should by no means be in holy orders, by the fact of there being three successive lay head masters of York Cathedral Grammar School in the same century, and by the provision in several foundations of Obits at Winchester College by which the head master, was paid less for his attendance at the Obit if he was a layman than if he was a priest. As to the curriculum, or as Colet expressed it, 'What shalbe taught', he laid down none. 'What shalbe taught it passith my wit to devyse and determyn in particuler'. But 'in generall' he would they were taught 'all way in good litterature with laten and greke and goode auctors such as have the veray Romayne eliquence joyned withe wisdome, specially Cristyn auctours that wrote theyre wysdome with clene and chast laten other in verse or in prose'. For he says his great aim is to increase knowledge and 'good Cristen lyff and maners' - conduct and character being with him, as with his predecessors, the first object. So he puts first the English catechism, which he had himself written, then

[page 280]

Erasmus's Institute of a Christian, and then 'other auctoures Christian', and reels off the names of those Latin Christian poets of the third to the fifth centuries, Lactantius and the rest, mentioned in Alcuin's School Library at York, adding Baptista Mantuanus, the friar who, only some twenty years before, wrote Eclogues in imitation of the great Mantuan, Virgil, intended to supersede those of his predecessors because they were chaste and Christian. He was still used as a schoolbook in Shakespeare's time, who makes Sir Hugh Evans quote the good old Mantuan. Colet adds such other authors as most conduce to true Latin speaking, and goes on to abuse 'all Latin adulterate' which 'ignorant blynde folis' brought into this world and poisoned the old Latin speech and the 'varay Roman tongue'. But he shows his incapacity as a critic of the very Roman tongue, by speaking of its being used by Cicero and Terence and Virgil, as well as St. Jerome and 'seint Austen'. This was, however, not progress but reaction; it was not promoting humanism, but reverting to theological prepossessions.

It is true he adds such other authors 'as shalbe thoughte convenyent and most to purpose unto the true laten spech'. Finally he says, in a passage which has made the statute world-famous, 'that fylthynesse and all such abusyon which the later blynde worlde brought in, which more ratheyr may be callid blotterature thenne litterature I utterly abbanysh and exclude oute of this scole'.

As we have shown, there is reason to believe that both Winchester and Eton had taught Greek before this. The odd thing is that there is some reason to suppose that Greek was not taught at St. Paul's after this, or at least not after Lily's time. For, while copious efforts in Greek appear in the verses with which Winchester saluted Edward VI and with which Winchester and Eton saluted Elizabeth, the only Pauline effort of the same kind preserved, which greeted Elizabeth on her entry into London in 1560 or 1570 - the date is disputed - are much less in quantity and contain no Greek, but only Latin.

The fame of Colet's re-foundation was really due to its transferring the government of the oldest and most famous school of the city and the cathedral from the Dean and

[page 281]

Chapter to a city company of lay and married men; to its being made by far the largest free school in the city, for a hundred and fifty-three boys instead of only twenty-five at the Mercers' own school, or twelve at St. Anthony's; to its being the richest, and, above all, to the encomiums of Erasmus, who boomed it, as the German reformers a few years afterwards boomed the similar re-foundation of Strassburg School by Sturm.

A great many of the other schools credited to Henry VIII's time were, like Colet's, not new foundations but revivals, augmentations or conversions into free schools of old schools which were not free. It may be strongly suspected that this was the case with Wolverhampton Grammar School, for the erection of which Sir Stephen Jenyns, Merchant Taylor and ex-Lord Mayor, had obtained a charter on 22 September, 1511, having previously bought the ground 'for the education of boys and youths in good manners and literature and for the better maintenance of a master and usher of the same'. It is impossible to believe that the ancient collegiate church of Wolverhampton of Saxon foundation had not, like Warwick and other ancient collegiate churches, kept a grammar school, though probably its endowment was some anciently fixed payment of £2 a year or so, and therefore inadequate for the sixteenth century and free education.

So when we find the 'scolemaster' at Stafford, reckoned as but denied by the inhabitants to be a chantry in the collegiate church of St. Mary there (which church is said in the certificate at its dissolution to have been founded by King John but in fact appears in Domesday), we may feel sure that the scolemaster-chantry was a later and additional endowment of the school always maintained by the college.

Similarly with the Morrow Mass-priest and Schoolmaster at Tamworth in the chapel of St. George in the collegiate church of St. Edith 'founded by King Edgar', whose duty was 'to teche a free scole', the endowment of £12 10s. 3½d. must have been a comparatively recent one in substitution for, or in augmentation of that of the foundation grammar school.

The same remark applies to another school, of some fame

[page 282]

because it was founded by Henry VIII's own grandmother, the Lady Margaret Tudor, who instituted the first free theological lectures at Oxford and Cambridge through the Lady Margaret Professors of Divinity, that of Wimborne Minster, Dorset. This was to be a free grammar school for all and singular coming there to be instructed in grammar, to be taught freely and gratis in the form and manner and at all and singular such times as is, was or shall be used in the Grammar School at Eton or Winchester, and the master was to be appointed by the master and fellows of Christ's, her College at Cambridge. But though the ordinances for it were made by Bishops Fox of Winchester and Fisher of Rochester on 12 March, 2 Henry VIII., i.e. 1511 (not 1509 or 1510 as the Endowed Schools Commissioners said) the licence for it had been given by Henry VII in 1497, and the endowment granted 3 February, 1504. Nor can we suppose that this ancient Saxon collegiate church had not always maintained a grammar school in some form. The Lady Margaret merely created a new chantry which is returned in the valuation of 1535 as the 'Scole maisters chauntrey' and annexed it to the schoolmaster's office permanently. She was in fact only doing permanently and by a new foundation what the Chapter of Southwell did in the same year 1504. The pay of the grammar schoolmaster there from the college was only £2 a year, having been settled at that in the twelfth century or thereabouts. So when St. Cuthbert's, the richest of the fifteen chantries in the minster, which had been founded by Archbishop Booth in 1479, fell vacant on 3 December, 1504, and the senior vicar choral asked to be given it by customary right, the Chapter answered that his petition was just, but requested him to abandon it this time for the public benefit and his own, so that they might present a fit chaplain able to teach the grammar school. Finally he acceded to their request, whereupon they instituted, invested and installed Sir William Babyngton, who then of his own free will and not under compulsion swore on the holy gospels that he would undergo the charge of teaching the grammar school the whole time that he held the chantry. This he held for at least thirty-six years, until the surrender of the college to Henry VIII in 1540, to be refounded by Act of Parliament in 1543.

[page 283]

Oddly enough when Southwell Minster was again dissolved under the Chantries Act in 1548, - the school being continued with a payment of £10 a year charged on the Crown revenues of Notts - this chantry endowment was in 1553 annexed to Guildford Grammar School, then refounded, one of the schools quoted by Mr. Mullinger in the Cambridge Modern History in 1910, in teeth of the evidence, as one of Edward VI's creations where no school had been before. In fact Guildford Grammar School is the earliest school endowed under Henry VIII, for founded it probably was not. But by will of 3 November, 1509, Robert Bekyngham, citizen and grocer of London, gave all his lands in Bromley and Newington 'to make a fre scole in the towne of Guildford or other works and deeds of charitie'. By deed of 4 May, 1512, the lands in Bromley were conveyed for that purpose, the appointment of the master being vested in the mayor and four 'of his most sadd and discreete brethren', and the school was established. Master Nicholas Elyott appeared as master in 1520. The only complete account of the old school endowment, preserved among the Corporation Records, for 1545, shows an income of £8 15s. 6d. of which only half was derived from Bekingham's Bromley lands, the rest from lands in Guildford, possibly the endowment of the previous school which must have existed there. By patent of 27 January, 1553, Edward VI, refounded the school and gave his name to it, and, by way of endowment two rent charges which formed the endowments of a chantry at Stoke d'Abernon and the Southwell chantry above mentioned. Under Mary, Archbishop Heath, being chancellor, recovered the Southwell chantry for Southwell Minster, then re-established, by forgery, making five distinct erasures and additions on the rolls in his custody. By Act of Parliament under Elizabeth, when Heath was deposed, St. Cuthbert's chantry endowment was restored to Guildford school. Being unfortunately a fixed rent charge on the manor of Battersea it has not proved of much value in later times. Its chequered career is a striking instance of the Edwardian School foundations, so-called, robbing Peter to pay Paul, and of the looseness of historians in dealing with them.

Another school, which dates from the first year of Henry VIII, though commonly attributed to Queen Elizabeth, who

[page 284]

gave it only a new charter, is Blackburn Grammar School, Lancashire. A deed in English of 4 April, 1514, states that the church reves (churchwardens) and parochyens had bought (in the first year of King Henry, according to a later bill in Chancery) lands for an 'honest, seculer prest, and no reguler, suffyciently lerned in gramer and playn song, if any such can be gettyn, that shall kape contenually a Free Gramer Scole'. To the lands so bought by the parishioners, the Earl of Derby contributed a piece of land worth 14s. a year, in consideration of which he was by the deed called founder and patron, and given the appointment of the chantry-priest-schoolmaster. A rather remarkable provision was that if a man sufficiently learned to teach grammar could not be found, at least one who could keep a Free Song School should be put in.

The next two schools credited to Henry VIII's reign, those of Lewes and Nottingham in 1512, were certainly not wholly new creations. We have seen that the school at Lewes was flourishing in the thirteenth century. So when Agnes Morley, widow, made her wills on 20 November, 1511, and 24 May, 1512, giving a scolehouse, and a rent charge of £20, which she had bought 16 December, 1508, for a 'scole maister and usher to the use and performacion of a fre scole', the master to be 'a prest able to teche gramer having no cure of souls or other lette whereby he might draw his attendaunce from the said scole' she was augmenting and perhaps freeing, not founding, a school de novo.

The same was the case with Nottingham Grammar School, similarly endowed as a free school by Agnes Mellers, 'wydowe and vowesse' under licence of 22 November, 1512, by deed dated 2 February, 1512-3, with strict injunctions against either master or usher having or using 'any potacions, cocke-fight or drinking with his or their wiffe at wiffes' hoost or hoostices, but onely twise in the yere, nor take any other giftes or avayles whereby the scholers or their frendes should be charged'. This school as we saw appears in records of the Archbishop, of Southwell Minster, and of the borough of Nottingham from the thirteenth century, though struggling with debt and rival schoolmasters, through insufficient endowment.

In like manner at Bruton in Somerset, endowed by

[page 285]

Richard FitzJames, Bishop of London, and his nephew the Lord Chief Justice, by deed of 27 September, 1519. There are clear indications, of a school before, in wills of 1417, 1507 and 1515. Yet this is one of the schools usually quoted as a product of the generosity of Edward VI, because he restored the old endowment in 1550.

Another school, that of Saffron Walden in Essex - of some note in educational history, since it had been claimed through an egregious blunder as the first school in England in which Greek was taught, and by another blunder its supposed curriculum was quoted as the earliest known - has been attributed to Henry VIII as founded in 1525 by Dame Johane Bradbury, sister and heir of the Vicar of Walden, John Leche, and by the Trinity Gild, itself founded by Henry VIII in 1514. The dates are correct enough as far as they go. John Leche did in fact by deed of 3 December, 1517, give lands to the Trinity Gild, in order that when they could find £10 a year their second 'preest shall be a profound gramarion to the intent that he may teche gramar within the towne after the fourme of the scole of Wynchestre or of Eton'. A new schoolhouse was built by Leche and his sister. The gild was not, however, founded by him or by Henry VIII. It existed before 1389, when in the return made into Chancery in consequence of the panic about gilds due to the peasants' revolt, it is stated to have been begun by John Rote, William Haveryll and others to find fifty torches to be burnt in honour of the Trinity at the elevation of the host on Sundays and feast days and a priest at the Trinity altar in the parish church. It had then no endowment but was maintained by yearly subscriptions. There were two other gilds, the Corpus Christi Gild, founded in 1377, which had an endowment of £1 a year in land, and All Saints' Gild.

On 23 December, 1423, Sir John Bernard and William Brynge, chaplains, were summoned before John Hatfield, abbot of Walden, to show why and on what authority they practised the exercise of teaching small boys of Walden, and instructing them in the alphabet, the graces and other higher books, without asking or obtaining leave from the abbot, though they had previously been reproved for their presumption in doing this, and though according to the statutes and customs of the

[page 286]

monastery the faculty of granting and conferring schools on grammar masters in the town of Walden and preferring masters to such schools belonged wholly and solely to the abbot and convent. The two chaplains confessed their offence and submitted themselves to the abbot, who interdicted them from teaching any boys of Walden in the alphabet or graces or other higher books. But eventually on the instance of the approved and more substantial men of Walden then present who wished their boys to be taught the alphabet, the chaplains were allowed to teach one boy of each inhabitant the alphabet and graces but no higher books. The 'graces' in question were the graces before and after meat, usually included with the alphabet in primers and horn-books. They were not the graces taught by a master in deportment, though a certain learned lady was barely prevented from alleging this as an instance of the progress of civilization and manners among the lower middle class in the towns of the fifteenth century. Still less was the licence one to teach the Greek alphabet as Lord Braybrooke stated in his History of Audley End, reading alphabeticis graecis for alphabetis et graciis and claiming Saffron Walden as the first school in England to teach Greek, nearly half a century before the first lecture in Greek given at Oxford. The licence granted to the chaplains, who were no doubt the chantry priests of two of the three gilds, was a limited licence, confining them to the function of a song or elementary schoolmaster, to teach reading and singing only, and intended to prevent their poaching on the preserve of the grammar schoolmaster, whose existence was guessed from the record of this incident. It is now capable of exact demonstration, thanks to the researches of Mr. E. and Mr. C. H. Emson. The transcripts by the former from the records, till now tossed in dust and confusion in the room over the church porch, show Walter scolemayster witnessing a deed in 1401 and a Walter, clerk of Walden, a grantee with others, evidently as a trustee of land in Walden, while a croft conveyed in 1407 is described as abutting on a messuage of Walter, scolemayster, and others. He is probably the same person who in 1416, 1418, 1425, 1436 and 1440, appears as Walter Payn of Walden, scolemaister, in 1431 as scolemeaster, and in 1447 as Walter Payn of Walden, scolmayster, deceased. Walter Payn then

[page 287]

was the master who in 1423 instigated the abbot to suppress the chantry priests who were trespassing on his domain of grammar. Nor was he the first of his tribe. In the Walden Abbey chartulary of the fourteenth century there appears as witness of many deeds from December, 1317, to 20 April, 1337, Master Reginald of the school (de scolis and de scola) or, as he is more usually called, Reginald Schoolmaster (magister scolarum) of Walden; while in the municipal records from 1342 to 1345 the same person apparently appears as Reginald of Crek, probably Creyk, Norfolk, schoolmaster of Walden. It is probable that both of them drew the deeds they witnessed, as was certainly the case with James Rogerson, described in a deed of 6 July, 1511, in which with a number of others he was grantee of land in the market-place, as 'instructor of the grammar school and notary public'.

The so-called foundation of the Trinity Gild in 1514 was a consolidation of the three old gilds and augmentation by 'Master Leche' who in the earliest extant account of the gild, for the year 1546-7, is called the founder. Master Leche's gift for the school had partly failed through defect of title, so his sister by deed of 18 May, 1525, substituted a rent charge of £12 a year out of the manor of Willinghall Spain, belonging to Walden Abbey, which she bought from the abbey, for the original gift - much to the loss of the school in the result - as the fixed rent has remained fixed while the rent of the original lands would have grown with the growth of riches.

Master Leche having directed his school 'use' to be that of Winchester and Eton, the alderman obtained from the masters there, a statement of their curricula, copies of which were entered in the alderman's, now the mayor's book. The first page of this document, which would no doubt have shown its origin, is unfortunately lost, and so when it was printed in Archæologia by that industrious antiquary Thomas Wright, he gave it as the time-table of Saffron Walden School, and as such it was quoted even in the History of Eton.

There were, however, a good many schools founded in Henry VIII's reign at places where, so far as is known, no school existed before; but most of these schools, being planted in places selected because they were the founder's birthplace

[page 288]

or abode and not because there was a population with a real demand for a school, have, except when they have become boarding-schools, not been very successful.

One of the earliest of these was Pocklington in the East Riding of Yorkshire, founded under a patent of 24 May, 1514, as a Gild of the Name of Jesus, the Virgin and St. Nicholas, by John Dowman, LL.D. of Cambridge, a Chancery lawyer, archdeacon, and so on. To it were added by deed of 1 December, 1525, five scholarships for boys from the school at St. John's College, Cambridge. The master was endowed with the magnificent stipend of £16 16s. 4d., that of Henry VI's foundations of Eton and St. Anthony's, London. Fortunately there was some flaw in the conveyancing, and this school retains its old endowment through being re-founded by Private Act of Parliament in 1549, after being confiscated to Edward VI under the Chantries Act.

Another new school was that founded in 1520 by Bishop Robert IV of Chichester, Robert Sherborne, at Rolleston, Staffordshire, 'where I was born and by the grace of baptism re-born', as he says. Sherborne had been a scholar of Winchester and of New College, and then a canon lawyer and Chancery official, Master of St. Cross Hospital and Dean of St. Paul's before being made Bishop, first of St David's, then of Chichester. He tried to make his foundation a smaller Winchester, giving the appointment of the master to the Warden of New College and directing even the prayers in school to follow those of Winchester, which he sets out in his beautifully illuminated statutes for the purpose. They form one of the most interesting educational documents of the date. They are not confined to a bare legal definition of the schoolmaster's salary and method of appointment, and the government of the school (which was vested in Mr. Thomas Rolleston of that ilk and his heirs male, together with the churchwardens), but also give the founder's views on school methods. For instance, they direct that the master is to pay attention to and often ask where in men's judgment is the grammar school of best repute for advancement of learning, what style of teaching and what authors it uses; and as far as he can to imitate those whom he understands by results are most proficient in teaching. Sound advice, not always followed! Among other

[page 289]

nice directions is one that the master is to look after the boys' manners and dress as well as learning, and particularly that 'their bodies are free from worms and their clothes whole'. The clever boys he is to press on, so that they may act as pupil teachers (pedagogos) to teach small boys who may be brought to him, the alphabet and first rudiments. He is to take particular care of the clever boys, while the stupid, the lazy, and those in human judgment incapable of learning he is to sharpen as far as he can by reading, writing and casting accounts, lest they should seem to have come to this our school for nothing.

If the master gets in a 'bate', as Mr. Horman says, he is to follow Plato's example, and dropping the subject which makes him angry, pass on to some other boy or another subject until he has cooled down. For the master must set a good example, and that is a 'vulgar',

Turpe est doctori cum culpa redarguit ipsum

On the teacher the shame

When his is the blame.

'And indeed this age has seen teachers who had far better have been asleep than teaching like maniacs.' Sherborne would have his master remember that blindness is to be enlightened by skill, not by force, and imitate Ipocrates, the prince of doctors, with his aphorism 'that we ought to lead nature where it wishes to go'.

If a boy at the beginning has grasped even one thing he is to praise him vehemently with this or the like good saying:

Omni bina die si discam verba sophiae

De parvo puero clericus aptus ero,

which may be Englished:

Two words of wisdom mastered every day

Make clever clerk, and drive dull boy away.

But all those words of wisdom were thrown away. Not being able to find any land for sale near Rolleston for the endowment of the school, Sherborne gave £500 to the Dean and Chapter of Chichester for a perpetual rent charge of £10 a year. That is still duly paid. The result is that the school which was to take Winchester for its model is now a public elementary school.

The next school was founded not by a successful cleric but

[page 290]

by a prosperous citizen and took as its model not Winchester but Eton.

Edmund Flower, 'citizein and marchaunt tailor', of London, in his will, 11 July, 1521, said 'I for certeine years past at my costs and charge have caused a free Gramer Scole to be maintained and kepte at Cukfelde for the erudicion and lernyng of pore scolers thedur resortyng'. As he had made his fortune by 1504, he probably started the school soon after, and endowed it on his death by will, which was proved 13 August, 1521, for a graduate 'beyng a secular prest and sufficient man to teche Gramer' to be 'always resident there to teche gramer' with lands to the value of £5 a year. A further endowment was given by William Spicer, parson of Balcombe, on 1 October, 1528, who expressly provided that the schoolmaster 'shall teach the scholars in the said school grammar after the form order and usage used and taught in the Grammar School at Eton near Windsor from form to form'. To this end, a time-table was sent from Eton, which is fully set out in the Cuckfield statutes, and it was enjoined that these 'acts and orders' were only to 'continue until such time as the Controlers be certified of others being used and taught in Eton more profitable to scholars'. Unfortunately we have only a corrupt copy of a later date of this, the earliest specimen of an Eton time-table preserved.

Another school in Sussex, Horsham, was founded by a man of the same type, Richard Collyer, citizen and mercer of London, by will 23 January, 1532-3. A house was to be built for a free school, 'in which house to be threescore scolars', the master to have £10 a year for his 'wagis,' the usher £5. The said 'scolars were to be at noo charge of their scole hire, but freely without any money paying therfor', and preference was to be given to the poor of Horsham and the neighbourhood, 'for consideracion gentilmen and other men be in better habilitie than poore men be', but no one from the parish was to be refused. The appointment of master and scholars was given to the vicar and inhabitants, but the management of the estates to the Mercers' Company, which did not prove of advantage to the school, as they took all surplus income for themselves.

In 1523 the inhabitants of Berkhampstead agreed to

[page 291]

devote all the lands of their brotherhood to finding a schoolmaster to teach their children and to the building of a school to teach in. John Incent, Dean of St. Paul's, being president of the fraternity, gave all his lands there to be joined with the brotherhood lands for the same purpose. Further, on 14 October, 1541, John Incent obtained a licence to found a chantry and also 'one Free Scole within the towne of Berkhampstedde, of one mete man being a scolemaster, and one other mete man being an ussher for the techyng of children in grammer frely, withoute any exaccion or request of money for the teaching of the same children, not exceeding the nombre of one hundreth fourty and four'. After the founder's death, the King 'as principal founder' was to present the chief master and teacher, and the Dean of St. Paul's the usher. An Elizabethan account of the school which the dean built, and which still stands, says 'Th'ole building is so strong an faire that the like Grammar Schoole for that point is not to be scene in the whole realme of England'. An ex-fellow of All Souls' College himself, he made Richard Rive, or Ryves, a fellow of that college, the master, with an usher and a chaplain, or petties' master, as at Colet's new school at St. Paul's.

This school has been lately selected for special notice by a Professor of History in the University of London as one of three schools founded by Edward VI, where no school was before, and as thus effectually disproving the wanton assertion, made by the present writer, that none of the Edwardian Grammar Schools were really his creation. Professor Pollard cited as proof an Act of Parliament for Berkhampsted School passed in 1548. Had the professor, however, looked at the Act he professed to quote he would have seen that it recited Incent's foundation and alleged a flaw in the conveyancing of the property, which was therefore claimed by Andrew Incent, the founder's cousin and heir. The Act negatived this claim and corrected the alleged flaw by a re-foundation; Rive and his usher and their successors being incorporated as 'Master and Usher of the Free School of King Edward VI in Berkhampstead', a title which has deceived the unsuspecting professor.

Another case, that of Stamford Grammar School, cited in

[page 292]

the same connexion by the same professor to support the same allegation of Edwardian initiative, showed even greater abstinence from research and regard for facts on the professor's part. The Act of Parliament of Edward VI for this school in 1548 recited the endowment by William Radcliff's will and the fact that 'for 17 or 18 years since his death an honest learned schoolmaster had taught according to the mind and intent of the same William Radcliff greatly to the benefit of the same poor towne and to the other townes thereto adjoyning.' It did not even profess to found or re-found the school, or call it Edward VI's Grammar School, but only made the Alderman of Stamford (a mayor had not yet been created) ex officio trustee and governing body of the school, vesting in him the property bequeathed by Radcliff. The professor need not even have taken the trouble to read the Act he professed to quote. For in the very book which he was attacking, English Schools at the Reformation, the certificate of Edward VI's Commissioners was printed, which showed the pre-existence of the school. The certificate gave the date, 1 June, 1532, and terms of the will of William Ratclif (so they spelt it) for the maintenance of a fit secular chaplain sufficiently learned, to celebrate for the soul of the said William and freely teach the art of grammar in 'Staunford', with a power to get a licence in mortmain for the Alderman of the Corpus Christi Gild to hold it, and also a finding that the school was being carried on under Libeus Byard, who enjoyed for his salary or stipend the rents of the lands given, amounting to £10 3s. 1d. gross, and £9 5s. 5d. net. The Commissioners actually directed this school to be continued, charging the salary on the Crown revenues, the chantry lands being confiscated. But the school had a friend at court in the person of one William Cecil, an 'old boy', who was M.P. for Stamford in the Parliament which passed the Chantries Act, and it cannot be doubted that it was through his influence, being Secretary of State, that the Act of Parliament was procured, which saved to the school the endowment, which it still enjoys, without, as usual, substituting the name of the cuckoo King for that of the previous benefactor. Ratclif, however, was not the creator of a new school. As we saw, there was evidence of the school's existence in 1309, in 1327, and 1389, and the Henri-

[page 293]

cian founder was therefore at the best only reviving and probably only refreshing an ancient institution.

An interesting school which may, or may not, have been first founded at this time is Basingstoke Grammar School. The Holy Ghost Gild 'the brotherhodd of the chapell of the Holly goost', was, before 1244, founded to maintain a priest in the picturesque chapel, the ruins of which are seen from the South-Western railway station. A chantry certificate in 1548 said that 'sythens', that is, at least since its legal incorporation under a licence of 16 November, 1524 - of which Bishop Fox has had the credit, though he apparently only lent his name as a petitioner for it - the endowment was 'employed to fynde a scole master to teche children grammer'; the master receiving £5 17s. 8d. a year. As no continuance order of Edward VI had been found, it was assumed by the present writer in the Victoria County History of Hampshire, that the school ceased by virtue of the Chantries Act, and was only resumed under the new charter or letters patent of Philip and Mary, 24 February, 1557, whence it is now called Queen Mary's School. This assumption now turns out to be wrong, the Ministers' accounts, since made available, disclosing the payment from the Crown revenues throughout Edward VI's reign of £5 17s. 3d. to Thomas Browne, 'schoolmaster of the grammar school founded by a certain gild called the Fraternitie in Basingstoke' under a warrant or continuance order made by Sir Walter Mildmay in 1548. The school therefore never ceased, and if any sovereign, rather than the people of Basingstoke, is to be regarded as its founder, that sovereign is Henry VIII, not his daughter. She, indeed, did on the request of Cardinal Pole, refound the gild, and restore its lands for a priest to celebrate in the chapel 'and for the instruction and education of the youths and boys of the said town'. The accounts of the resuscitated gild mention a schoolmaster in 1559. but not his name. In 1560 the vicar taught the school for £1 a quarter, and the vicar was the same Thomas Browne, a student of Christ Church, Oxford, who had been schoolmaster in 1548. He still taught occasionally during vacancies till 1567, what was always called, down to 1852, The Holy Ghost School. The continuity of this now flourishing school from at least 1524 is therefore definitely established.

[page 294]

Another of the schools which has been put down to Edward VI's foundation, Sedbergh in Yorkshire, was in fact founded in the earlier part of Henry VIII's reign by Roger Lupton, one of the successful much-beneficed lawyer-clerics of the day, and Provost of Eton, as we have seen, and Master in Chancery. He founded it as a Chantry-Grammar School, consisting of a single Chantry-priest-School master, in his native place. The date has been wrongly assigned to 1528. The true date is fixed as between 23 July, 1523, and 24 March, 1525, by two deeds of these dates. In the first a dispute was settled as to the ownership of the Loft-house, which Lupton gave for the master's house, showing it not then to be his. On the other hand, the deed of 24 March, 1525, made by the Archdeacon of Richmond as to seats in Sedbergh Church, says 'a place shall always be kept free for the chaplain and scholars celebrating the Lady Mass and anthem in the said chapel'; clearly showing that the school was already going on. This is further shown by a deed of 26 May, 1527, by which Lupton granted £600 to St. John's College, Cambridge, for six scholars to be incorporated among the other scholars of the college, and receive the same emoluments with £1 6s. 8d. more to pray for his soul. The scholars were to be born in England [i.e. not Scots] sons of freemen (libere condicionis) - a striking late testimony against the notion that colleges and schools were intended for the working classes, who were still mostly villeins - 'and who have issued well learned from my Grammar School of Sedbergh', with preference for founder's kin, natives of Sedbergh, Dent and Garstall, especially those whose friends had been benefactors to the foundation. In order that the college might get more learned scholars from his school he gave the appointment of the schoolmaster to the college, with preference for ex-Lupton scholars. To bring the school under the supervision of the college, as Winchester was under that of New College, he requested the master of the college, if he happened to go that way, to call and question the schoolmaster on the condition of the school, and examine the most advanced scholars and select the best for St. John's. If the master could not go, 'a fellow is to be elected, who because it is his native country or for some business is going there'. The deed

[page 295]

concluded with a proviso that if 'through the fraud and malice of men, which God avert, his Chantry and Grammar school at Sedbergh should be injuriously treated so as to come to an end', the endowment should go over to St. John's College for four more Lupton scholars on the same terms as far as possible, but with preference only for founder's kin.

The school is again spoken of as already existing in a deed of 12 August, 1527, by which Lupton obtained from the Abbot and Convent of Coverham, to whom Sedbergh Church and Rectory were impropriated, a grant of the site of the school, 'a little close by the churchyard called the schoolhouse-garth, of the yearly rent of 1s. 8d., on which a schoolhouse has been built by the same Master Roger Lupton for the institution of a free (gratuitam) school there for ever'. The later foundation deed of the school, long assumed to have been lost, but produced by the present Master of St. John's College, Cambridge, when bursar, from among their muniments, a deed poll of 9 March, 1528, distinctly refers to a prior establishment of it in a provision that the chantry priest was to find at his own cost all things sufficient for the celebration of mass 'with that sufficient stuff I there left at the first endowment'. In this deed, Lupton recites that he has bought lands of the yearly value of £12 7s. 9d., besides a messuage called the Lofthouse, 'in the which Syr Henry Blomer, nowe chauntery pryst, dwellith', the rents of which are to be used for a chantry in the parish church, and for a chantry priest, who is to be 'sufficiently lerned and instructe to fulfyll the chauntery duteis and habyll to teche a gramer Scole'. He is to be continually resident, explained to mean not absent more than thirty days in the year, and during that time he is to provide 'one of hys Scolers sufficiently lernyd to teche hys Scolers in hys absens'. He is to say mass every day in the church and pray for the souls of the founder and others, and to 'rule and order the grammer Scole as master, and teche frely gramer, after the maner, forme and use of some lawdable, notable and famous Scole of England, and in especiall my kynsmen and theym of Sedber, Dent and Garstall, and then all other, without ony exaccion or calenge of theyr stipend or wages besyde my allowaunce'. 'But', Lupton continues, 'the sayd mayster of the

[page 296]

grammer Scole shall not be bounde to teche, ne cause no scoler of hys to teche any other thyng but gramer to any chyldern, except the frends of the sayd chyldern wyll gyffe to the seyd Scolemaster, or to the Scoler, with the masters assent, that shall teche theym, for theyr labour as they can agree with the sayd Scolemaster and Scoler that shall teche theym, so that the sayd Scolemaster or sayd Scoler be no letted to teche grammer'. A further endowment was given by Lupton to St. John's College for two more Lupton scholars there, making eight in all, by deed of 7 June, 1535. A few months later he retired from the provostship at Eton, to his canonry at Windsor, where he died in 1540. He did not mention Sedbergh School in his will.

Henry Blomer, the first master, held office till his death. By his will, 5 November, 1543, he gave £6 13s. 4d. to St. John's College for the Lupton scholars, on condition that all the scholars were elected from Sedbergh School, that proviso having been omitted from Lupton's deed of 7 June, 1535. Blomer also gave to his successor for the use of the 'Free School at Sedbergh, 6 silver spoons, with such certain of my books as shall be delivered by indenture, at the discretion of my executors to remain as heir looms to the said foundation'.

He was succeeded by Robert Hebblethwaite, a fellow of St. John's College, who gave him a testimonial on 27 January, 1543-4. Some difficulty about his admission arose with the feoffees at Sedbergh, and the rents being withheld from him, the College appealed in a letter written by the celebrated Roger Ascham, then in residence at St. John's, to Robert Holgate, Bishop of Llandaff, and President of the Council of the North, 'to prevent any violence or injustice being offered to the school, and to so repress and punish the greed of these men that the rest may learn what is the result of making an attack on the schools and ease' (otia, a Latinization of the Greek scholas) 'of youth, which are the very foundations of all that is best in the commonwealth'. Hebblethwaite was in possession when the endowment was confiscated and sold by Edward VI in 1548.

Manchester Grammar School can hardly be ascribed to Henry VIII's reign, though it received a great increase in endowment then. It was probably part of the collegiate church

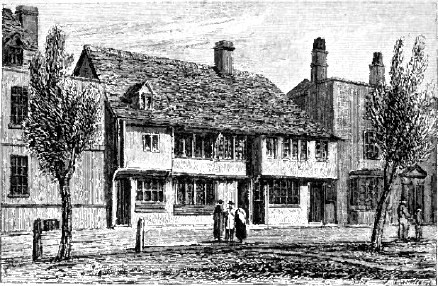

[facing page 296]

THE MANCHESTER GRAMMAR SCHOOLMASTER SLAYING THE DRAGON OF IGNORANCE, 1508

THE MANCHESTER GRAMMAR SCHOOLMASTER SLAYING THE DRAGON OF IGNORANCE, 1508

THE MANCHESTER GRAMMAR SCHOOL USHER LICKING HIS CUBS INTO SHAPE, 1508

MISERICORDS IN MANCHESTER COLLEGIATE CHURCH, NOW THE CATHEDRAL

THE MANCHESTER GRAMMAR SCHOOL USHER LICKING HIS CUBS INTO SHAPE, 1508

MISERICORDS IN MANCHESTER COLLEGIATE CHURCH, NOW THE CATHEDRAL

[page 297]

founded in 1420, as stalls, erected in the choir of the church between 1506 and 1512, assigned to the Archididascalus and Hypodidascalus, are strong evidence of the existence of the school before that date. A chantry founded by Alexander or Richard Bessike in 1506 for two priests, 'thone of the two' to teach a free school, was its first separate endowment. Hugh Oldham, a Chancery official and pluralist cleric, afterwards Bishop of Exeter, gave corn-mills in 1515 to the warden and fellows of the college by a Latin deed for the endowment of a 'fit person, secular or regular, learned and able, to be schoolmaster to teach and instruct grammar in the town of Manchester, according to the form of grammar now learned and taught in the school of the town of Banbury in the county of Oxford, which in English is called Stanbridge Grammar, and an usher as a deputy or substitute of such person'. They covenanted to pay the master £10 and the usher £5; and the master took oath to 'teach and correct all their boys and scholars equally and impartially' and not to take 'any presents, gifts or any kind of thing by colour of their service or office or teaching, except their stipend only, without any fraud, cunning and device'. They were to attend choir in surplices, 'like other fellows of the college', and every Wednesday and Friday go in procession with their scholars before the warden round the cemetery or church or otherwise. Oldham died, 25 June, 1519. Six years afterwards Ralph Hulme, gentleman, one of the trustees, turned out to be a fraudulent solicitor and claimed the mills and lands as his own, and it was only by special efforts on the part of John Lord Warr, who said he had only sold the mills for the free school (libere scole) of Manchester, that the endowment was saved. For some obscure legal reason, perhaps because there was no licence in mortmain, a new settlement of the endowment was made, this time in English, on 1 April, 1525, which is commonly reputed the original foundation deed. It constituted, instead of the college, an entirely new body of twelve lay trustees, and the master was to be appointed by Corpus Christi College, Oxford, instead of by the chapter of the collegiate church. He was to be a 'syngilman', priest or no priest 'so that he be no religiouse man', i.e., no monk, regular canon or friar, 'able to teche childeryn gramyar after the maner and forme of the Scole of Banbury,

[page 298]

wiche is called Stanbryge gramyer'. Most of the provisions as to the school are adapted from the statutes of St. Paul's, and the head master has retained, like him of St. Paul's, the name of high master.

The chief educational foundation in Henry VIII's reign was that of Cardinal's Colleges at Oxford and at Ipswich by Cardinal Wolsey. Ipswich was an already existing school, and had been endowed on 2 January, 1482-3 by an ex-'Portman' or Mayor, Richard Felar, the master receiving £5 a year, in addition, however, at least from 1420, to the chaplaincy of the Corpus Christi Gild. When in 1528 Wolsey built his beautiful college of red brick, of which only one gateway now remains, and endowed it out of eleven Priories suppressed for the purpose, for a dean, twelve fellows, eight choristers, and fifty children or scholars, a schoolmaster and two ushers, he was careful to get a grant from Bailiffs, Portmen and inhabitants of Ipswich of the old school and its endowment. But on 19 September, 1530, the college was declared forfeited to the Crown and only a fragment of the endowment afterwards given to the school.

Space does not permit an account of all the other schools founded, or which first occur under Henry VIII, before the meeting of the Reformation Parliament. We can but afford them that which in the Roman breviary is directed to be given to a saint whose commemoration falls on a day dedicated to some greater saint, memoria tantum, a mere mention. There were founded chantry schools at Rock in Worcestershire, by Sir Humphry Connysbie, knight, 1509; Chesterford, Essex, by William Holden, 1514; Owston, Yorkshire, by Robert Henryson, 1514; Houghton Regis, Bedfordshire, by William Dyve, mercer of London, by deed 1515; also in 1515, Liverpool, a priest 'to say masse afore the ymage of Saynt Katherine within the chappell of Liverpool' (St. Mary del Key or Quay) and 'keepe gramer scole', free for all 'whose names be Crosse and poor children', by John Crosse, a London rector; chantry schools at Kinver, Salop, by John Perot the same year; Cannock, Staffordshire, about 1518; East Retford, Notts, school built by Thomas Gunthorpe in 1518, supported out of chantry lands; Earl's Colne, Essex, by deed of Christopher Swallow, vicar of Messing, 1519. There was set up

[facing page 298]

DOORWAY, CARDINAL COLLEGE, IPSWICH, 1527

DOORWAY, CARDINAL COLLEGE, IPSWICH, 1527

[page 299]

at Warrington a 'fre gramer scole', by will of Sir Thomas Boteler, 16 August, 1520, 'to be the very clear lanthorn of good example in virtuous living to all the country thereabouts', according to Ordinances, to be made, which were made in 1526; at Milton Abbas, Dorset, a 'fre scole' was founded by Sir John Leder, priest, 1521; at Tenterden, Kent, by William Marshall, the same year. At Hornby, Lancashire, a school and hospital were directed by will of Lord Monteagle, 1523; at Leyland, Lancashire, by deed of Sir Henry ffarington, knight, 1524; at Bolton-le-Moors, a grammar school was endowed by grant of William Haigh to parishioners, 4 March, 1524, further endowed in 1623, 1642, by Robert Lever, and in 1895, 1902, and 1913, by W. H. Lever, of Port Sunlight fame. At Kneesall, Nottinghamshire, the will of John Chapman, notary public, citizen, and mercer of York, Count Palatine of the holy palace of the Lateran, and registrar of the Cardinal-Archbishop, 4 March, 1527-8, established a school.

At St. Michael-upon-Wyre, Lancashire, St. Katharine's chantry school, founded by deed of John Butler, 3 December, 1528, is not heard of after 1642. At Winwick, a free grammar school was founded by Gwalter Legh, ancestor of Lord Newton; at Kirkoswald, Yorkshire, a collegiate church with Grammar and Song Schools was founded by deed of Lord Dacre in 1530.

Schools of unascertained date appear in the Valor Ecdesiasticus of 1535 at Higham, Kent, a chantry with income of £6 13s. 4d.; Kingsley, Staffordshire, a chantry or priest's service founded by Hugh Adderley, clerk, daily to celebrate at the Altar of Jesus and 'to kepe scole and to teche pore men's children of the said parishe grammer, and to rede and sing', yearly value £6 1s.; Orford, Suffolk, chantry at our Lady's Altar and school, income £5 9s. 9¾d.; Shenston, Staffordshire, a priest at the altar of Thomas a Becket in a chapel attached to the church, founded under the will of James Keyley, receiving £7 0s. 4½d. a year, 'to teche yong children of the parish grammer, or otherwise accordyng to his knowledge'; Thirsk, Yorkshire, chantry of Our Lady, founded by divers well-disposed persons, to help service and teach a grammar school, income £5 10s. 4d.; Weobley, Herefordshire, the priest in chapel of St. Nicholas in the church, founded by John Chapman and Alice Baker, 'to kepe a scole and

[page 300]

teache chyldern, and brynge them upe in vertue', clear income £6 13s. 1d.

Childrey, Berks, where a school and almshouse were placed under the tutelage of Queen's College, Oxford, by Sir William Fettiplace on 20 July, 1526, calls for special notice, as it is an early instance of an elementary school, with an 'upper division' for those who want grammar or 'secondary' instruction. The foundation deed gives the full programme of a Song or Elementary School, which goes far to explain why the Reformers were disposed rather to destroy such schools as promoters of superstition than to preserve them as advancing education. The priest was indeed to be skilful and well used and sufficiently instructed and learned in grammar. But he was to teach in the first place, the alphabet, the Lord's Prayer, the Angel's Salutation, the Apostles' Creed, and all other things necessary for serving the priest at mass, together with the Psalm De Profundis, and collects and prayers for the dead; also to say grace as well at dinner as at supper; then, in English, the Fourteen Articles of Faith, the Ten Commandments of God, the seven deadly sins, the seven Sacraments, the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, the seven works of mercy as well corporeal as spiritual, and the manner of confession, necessary not only for the boys themselves, but in order that they might instruct others who were ignorant. Also he should teach them good manners, especially not to lie, and to honour their parents and in church to serve God devoutly. This curriculum savoured to the Protestant more of superstition than of religious education. One would like to know what proportion of the boys went on to the upper division. For this provision was made that if any were apt and disposed to learn grammar, the priest should instruct them in grammar in the best and most diligent manner he could, and especially teach them what was most useful to them, and what was most expedient according to his true estimation and the sound counsel of learned men. He was to exact nothing from the poor or parishioners, though he might take anything freely offered.

The darkness of our ignorance of the curriculum in our ancient schools is lightened for us first in 1528 by Wolsey's

[page 301]

statutes for his short-lived college and by the Eton time-table, set out as noticed above for Cuckfield Grammar School, in the same year, and a year or two later by the curriculum of Eton and part of that of Winchester as preserved at Saffron Walden.

Wolsey ordered his school to be divided into eight forms, the lowest learning the parts of speech and pronunciation. In the second form the boys were to talk Latin and turn into Latin 'some common proposition, not dull or inappropriate'. Their books, 'if any', were to be Lily's Carmen Monitorium, and the so-called Cato's Precepts, better known as the Moralia. In Form III. they were to read 'Æsop, who is wittier? Terence, who is more useful?' - for talking Latin be it understood - and Lily's Genders. In Form IV they went on in Lily's Grammar to preterites and supines, and in authors to Virgil, whose verses they were 'to give out with sonorous voice'. Form V was to read Cicero's Select Letters; VI, Sallust or Caesar; VII, Horace's Epistles, Ovid's Metamorphoses or Fasti; VIII, Valla's Elegantiae, Donatus' Figura, and any ancient authors in the Latin tongue, while Terence is to be studied with lectures on the life of the day, style and so forth. The boys were also to learn précis-making and to write essays.

At Eton in 1528 Stanbridge's Accidence was the first thing learnt; then 'after repeating the rules the Master shall cause them to make small and easy Latins, proper and such as the children may understand and delight in'. In the second form they read Whittington's Genders and Heteroclites besides doing Latins with the first form. Whittington was the master of Lichfield Grammar School, augmented by Bishop Smith, in connexion with St. John's Hospital there, about 1495. He re-edited and improved on Stanbridge's grammar. 'After their breakfast a lecture of Cato after the new interpretation shall be read to them, which they shall construe again at afternoon.' In the third form Whittington's Preterites, Supines, and Defectives were learnt by heart. Their 'books' were Terence, Erasmus's Similitudes or Colloquies and Virgil's Eclogues. The fourth form did their 'Latin constructions and other things, except rules, with the third form, to the intent that the better learned may instruct the less learned'; 'their rules were the Regiments of Whittington which he called Concinnitates Grammatices'. In the fifth they learnt the Versifying Rules; and for books

[page 302]

read Sallust, Virgil, Horace and Ovid's Epistles, and every week made verses and epistles. Horace and Cicero were added to these in the Sixth, which 'have for their rules Copiam Erasmi'. From the Order sent to Cuckfield in 1528 we see that there were only six forms at Eton, but in that sent to Saffron Walden only two years later, seven forms are mentioned both at Eton and Winchester.

At that time Eton had in the higher forms discarded Whittington's grammar for Lily's, long afterwards re-edited as the Eton Latin grammar, but used Stanbridge's grammar for the lower forms as did Winchester, patriotically, as he was a Wykehamist. The Winchester scheme of work has lost its first page and so starts in the middle of a sentence, 'Ovide Metamorphosesos the Thursday, Salust the Fryday, with the vij forme, and at afternone rendering of there rulys. The Saterday lyke as the vij forme. The Sonday lykewise.' Next comes the heading 'the Vth forme', to be followed by headings of 'the Third', 'the Seconde' and 'the Fyrst forme'. To any one acquainted with Winchester School or its history this was startling. For from time when the memory of man runneth not to the contrary up to the present day Winchester has known only three forms, called Sixth, Fifth and Fourth Book. It has been a subject of much discussion whether there ever were any other forms, and if so when the others disappeared. We learn for a fact that at Winchester, as then at contemporary Eton, and as at Westminster now, there was a Seventh Form above Sixth Book and three forms below Fourth Book.

The work of the Fifth and lower forms may be thus summarized. On coming into school at seven o'clock, from Monday to Thursday inclusive, the first business was the giving out of grammar rules. In the Fifth to Third Forms these were taken from Sulpicius, a schoolmaster at Rome, of Veroli in the Campagna, who published many grammatical works in Latin between 1487 and 1506. One of the Sixth Form gave them out to the Fifth, and one of the Fifth to the Fourth, but the usher gave them out to the Third. Form V did 'versifical rules' or rules for making verses; Form IV the rules for preterites and supines; and Form III, the rules for genders and heteroclites or irregular declensions, all of which were

[page 303]

separate works of the most heart-rending detail. Forms II and I took their rules from the Parvulorum and Vocabula, the Babies' Book and Word Book of Stanbridge. On Friday morning they were examined on these rules, and Friday afternoon 'rendered' them, which appears to mean said them by heart. After rules were given out, Forms V-III were examined on a verb which they had 'set up' overnight, and made 'vulgars' on it, i.e. Latin phrases, as in Horman's Vulgaria. V and IV together then 'write down the Latin that one of them shall make by the assignment of the Master', or as it is phrased for III, 'they have a theme to be made in Laten, the which Latyne one of the said forme at the pleasure of the master makith openlie dyverse ways. And after that they write the master's owne Latyne', that is, the master dictated his own version of the piece. Form V also learnt by heart Sallust on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, and four verses of Ovid's Metamorphoses on Thursday. For translation, or 'construction' as it is called (which was apparently done not 'up to books', i.e. in form, but in 'books chambers', sitting at their separate 'toys' or desks in chambers), they did Virgil's Eclogues every day except Friday and Saturday. On Friday they translated Tully's or, as we say, Cicero's Letters. On Wednesday they composed Latin verses; on Thursday, Latin Epistles. On Saturday, V and VI said twelve verses of Ovid 'without book' and were examined on them and showed up their Latin prose. In the afternoon they construed Cicero and showed up their epistles. The Fourth, instead of doing Virgil, did Terence from Monday to Thursday inclusive, which the master construed to them in the morning and they construed and parsed (parce) to the usher in the afternoon, and were examined in it on Saturday afternoon. Form III construed Æsop's Fables on Monday and Wednesday, and Lucian's Dialogues, presumably in Latin, on Tuesday and Thursday; while Forms II (and I?) construed Æsop's Fables every day except Saturday, when they had repetition of four verses of Cato and examination of it.

On Sunday the Sixth Form did 'lykewise' to the Seventh Form, and the Fifth Form did 'as the other hie formys dothe' but what they did is denied us through the loss of the first page. It was certainly not a day of rest. For the

[page 304]

Fourth Form on 'the Sunday with other low holy dayes' did 'an English of an epistle to be made in Latyn diverse wayes, and somtyme Tullie's paradoxes to be construyd', the Third Form had 'a dialogue of Lucyane or a fable of Æsop to be said without book and construed', and the First, and presumably the Second, 'a fabull of Æsope'.

The books used in the two higher forms can only be inferred from the Eton list. They were Horace or Cicero every day from Monday to Thursday, and on Friday and Saturday the Æneid of Virgil. For grammar they read Mosellanus' Figures of Speech. They made verses and epistles and read Erasmus Copiam verborum to help them. The most interesting thing about the two curricula is that both schools used Sulpicius, the recent Roman writer, the one for 'versifical rules', the other for his 'Quos decet in mensa' or table manners. Eton used the French schoolmaster Despautier's Method of writing letters or Ars Epistolica, first published at Strasburg in 1512, and a second edition at Antwerp in 1529, when he was master of the School of St. Ginnocus at Bergen-op-Zoom; so that it was quite the latest foreign school-book.

The school-books of the day were still under the influence of the over-refining spirit of dissection and classification, which had been imbibed from the schoolmen. Epistles, for instance, are divided by Despautier into three classes, the descriptive, the political and the familiar, while each letter is said to consist of a salutation, a statement, a petition, and a valediction or conclusion, though, as he naively remarks, all these characters are not always found together. All letters, in fact, were not begging letters. The treatises on versification dwindle down into the most appallingly minute rules, with exceptions more numerous than the rules, as to the quantities of the various vowels in different locations.

The medieval grammar was not made less maddening by being almost invariably in verse. In these late fifteenth and early sixteenth century writers the verses meandered like slender rivulets of text through meadows of marginal notes and prose commentary.

Arte novata aliqua dicendi forma figura est,

Sunt ejus species metaplasmus, schema, tropusque,

Schemata dant species tibi lexeos et dianeas.

[page 305]

Such is the exordium of the excellent Mosellanus, who is very scornful on his predecessors for occasionally sacrificing metre to sense, but as he can only avoid the fault by interlarding his discourse with Romanized Graecisms, the learner might well prefer the sacrifice. No doubt it sharpened the wits for such encounters as those theological controversies which soon overwhelmed the nation. But the practice of distinctions without differences and classifications without contents was responsible for a great deal of the word-splitting that sent men to the stake or the gallows on theological minutiae. The Quos decet in merisa of the Italian Sulpicius out of which the schools learnt at once manners, morals and Latin verse, is a much superior work. It got its name from its beginning:

Quos decet in mensa mores servare docentes

Virtuti ut studeas litterulisque simul.

Good manners for the table here we tell

To make our scholars gentlemen as well.

In elegant elegiacs are set out all the good old nursery rules as to behaviour. Boys are to have clean gowns, and before meals wash hands and face, clean their teeth and blow their noses. Part I then goes off into general maxims of conduct and morals. Never return abuse or lose your temper, avoid gluttony and idleness, do not be morose nor get too easy in your manner, and so forth.

Part II returns to manners strictly speaking. Spread the tables neatly, see that the trenchers (quadrantes) are clean. Don't champ your jaws when eating, sit upright, don't put your elbows on the table, take your food only with three fingers and in small mouthfuls. Remember that you eat to live and do not live to eat (Esse decet vivas, vivere non ut edas). Did Sulpicius invent this famous epigram? Use your napkin often (napkins were supplied at Winchester, as appears in the first account roll), don't bite your food but cut it, nor gnaw your bones. Only lift the cup with one hand, unless it's of the kind that Theseus or Bel used to hurl at an enemy; don't look over it while you are drinking, don't swallow it too fast or drain the pot, or whistle when you drink. Wipe your mouth after it, and wash your hands and mouth when you leave the table. Bend your knee, join your hands and say 'Prosit' for grace.

[page 306]

This book of Sulpicius is by no means original. The Babees Book, which gives its title to the amusing collection of English, Latin and French books on manners, published by Dr. Furnivall for the early English Text Society, was translated from the Latin somewhere about 1475. They all appear to be derived from a common original written by Facetus, a pseudonym of Johannes de Garlandia, an Englishman who wrote a Latin-English vocabulary and a treatise on manners in the thirteenth century, copies of which were in Winchester College Library ab initio, and which was frequently printed by Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson from 1500 and onwards.

The Eton 'Order' gives besides the curriculum an interesting general account of internal organisation. The only questions asked of a proposed new boy were 'whens he comyth, what frends he hathe; whether there be any plage'. School began at 6 a.m. - they got up at 5 - with prayers, ending at 9 with De profundis, and then to breakfast. In a quarter of an hour come again, i.e. 9.45, and school till dinner at 11 o'clock. Afternoon school 1 to 5, and then supper after another De profundis. The prefect system was in full vogue. Two prepositores, now called prepostors, to take the names of the absents in every form; two in the body, i.e. nave of the church, two in the choir. In every house a monitor. They go home two in two in order and have a monitor to see that they do till they come to their 'hostise' or Dame's door. Privy monitors to spy on the others 'how many master the will'. Prepostors everywhere; in the field when they play, 'for fyghtyng, rent clothes, blew eyes or sich like' prepostors for 'yll kept hedys, unwasshid faces, fowle clothis and sich other'. If there are four or five boys in a house 'monytors for chydyng and for Latyn spekyng'.

The prepostors were not themselves to keep order or punish so much as to report delinquents to the master. That the reports were not without results we may gather from the character given of Cox, the master who supplied this account, by Walter Haddon, in the conversation on flogging in schools reported by Roger Ascham, which was the occasion of his Scholemaster. The Secretary of State, Sir William Cecil, having expressed himself against flogging, Mr. Peters had

[page 307]

argued that it was both necessary and useful: 'the rod was the sword of justice of the school'. 'Then', writes Ascham, 'Mr. Haddon was fullie of Mr. Peter's opinion and said "That the best scholemaster of our time was the greatest beater", and named the person. "Though", quoth I, "it was his good fortune to send from his schole unto the university one of the best scholers indeede of our time, yet wise men do thincke that that came so to pass, rather by the great towardnesse of the scholer than by the great beating of the master; and whether this be true or no, you yourselfe are best witness."' This 'best scholemaster' and 'greatest beater' is commonly said to be Udal. But it is quite clear that Ascham was referring to Haddon's master, Cox. If Haddon had meant Udal, who was then dead, Ascham would not have hesitated to give his name; but Cox was still alive and a bishop, and therefore for obvious reasons the name was suppressed. The mistaken reference to Udal was originally made by James Bennett, 'master of the Boarding-School at Hoddesdon in Hertfordshire', in his edition of Ascham's Works in 1761, and has been blindly repeated ever since. Udal was no sparer of the rod. But Cox must have the credit, or otherwise, of being reputed by an old pupil the best schoolmaster and greatest beater of his age.

Cox's Elizabethan successor Malim, gave a time-table of the year as well as the week, an account of the feasts and holidays as well as the work. The net result was that hard as the whole schooldays were, each a ten-hours' day, there were only five or indeed four of them a week; and there were so many feasts that hardly a week could have passed without at least one whole or half holiday. For every greater feast day was a whole holiday, and on every eve of the 'greater doubles', feast days on which double rations were enjoyed, there was a partial holiday, no work being done after dinner at 11 a.m. Ash Wednesday was given up, not to lessons, but to confession to the fellows or conducts, each boy choosing his own confessor. On the obit of William Wayneflete, 13 January, every boy received 2d.; on 7 February, the obit of Provost Bost, there was a half holiday; on 27 February, the obit of Roger Lupton, every boy received 1d. and there was a holiday from dinner-time (11 a.m.); and on 26 May, the obit

[page 308]

of Henry VI, every boy had 2d. On Saturday before Easter 'while the custom flourished' of the Easter Sepulchre, three or four of the eldest boys chosen by the master at the request of the sacrist watched round the sepulchre with wax lights and torches, 'lest the Jews should steal the Lord'. At Easter the school did not break up, though, to judge from Winchester, there were extensive exeats for those who could go home. For all there was a ten-days' holiday (cessatum a publicis studiis). On May Day, St. Philip and St. James, those who wished got up at 4 a.m. to gather boughs of may; but with a curiously grandmotherly care, which shows a very different spirit from that commonly imputed to our scholastic ancestors, the licence was coupled with the proviso 'that they do not wet their feet'. The windows of Long Chamber were then hung with may and herbs.

'St. John Lateran before the Latin gate', 6 May, 'brings many advantages, for from now after dinner they had a siesta in school, until the prepostor of hall and the ostiarius call out 'Get up' (Surgite) at 3 p.m., when, they have beavers or bever,' an interval for drinking beer, the equivalent of the modern afternoon tea. Malim recalls the line: 'Porta Latina pilam, pulvinar, pocula prestat', i.e. 'St. John Lateran's day brings the ball, the bed, the beer'.

Ascension Day began the summer holidays, which lasted till the day before Corpus Christi Day, the Thursday after Trinity Sunday, anyone not present at evening chapel on that day being flogged. On St. John the Baptist's birthday, Midsummer Day, all the scholars went after evening prayers to a bonfire, made in the open space at the east end of chapel, and then, after the choir had sung their anthems, to a bever. On the eve of that day the boys adorned their chambers with pictures and verses on the 'life and gests of the Forerunner', which they wrote out with illuminations and stuck at the foot of their beds. As it was nearly nine before they went to bed, they were allowed to lie in bed till six on the feast itself instead of getting up at five. The same custom was observed on 29 June, St. Peter and St. Paul. The custom, of the Eton and Winchester match being always held on one of those two feast days is perhaps ultimately due to this celebration. On 7 July, the Translation of St. Thomas (Becket), there was also

[page 309]

a bonfire, but no verses. At Eton, as at Winchester, the boy-bishop was directed by the statutes to perform divine service on St. Nicholas's Day, 6 December, and not on the usual day, that of the Holy Innocents; to avoid clashing with the established boy-bishop celebrations of the choristers of the cathedral and of St. George's respectively. Originally mixed up with the boy-bishop was the custom that on St. Andrew's Day (30 November) the schoolmaster used to choose the best and most appropriate stage plays, i.e. plays of Terence or Plautus, 'which the boys perform sometimes in public during the Christmas holidays, not without the elegance of the games (sc. of Rome), before a popular audience'. Altogether the sixteenth-century schoolboy before the Reformation did not have such a bad time of it.

It is curious that at the very time when these curricula showing a diversity of grammars were sent to Saffron Walden, steps were being taken by Convocation, under Henry's guidance, to enforce uniformity in the school equally with uniformity in the Church. In 1529 it laid down, as often before, and with as little effect, that schoolmasters should be orthodox as well as learned, and teach the rudiments of faith as well as of grammar, and prohibited books likely to infect boys' minds being read in school. Convocation broke new ground, when it proceeded to complain that, often through the plague raging in places where public schools were, or through a master's death, a boy who had learnt grammar for a year or two under one teacher had to continue under another who had a different method, and was laughed at or put back accordingly. For remedy Convocation directed that only one grammar should be put before boys, and that one to be prescribed within a year by the Archbishop, and a committee of four bishops, four abbots, and four archdeacons.

This was probably the first step towards the universal, or at least general, adoption of, the grammar, the joint composition of Colet, Lily, and Erasmus, issued in 1513 by Colet to Lily, commonly known as Lily's Grammar, and adopted by Cardinal Wolsey for his school at Ipswich. It contained the Accidence in English and the Syntax in Latin. The preface to Wolsey's book dated 1528, printed by Peter Treveris in 1529, states that this grammar was already 'prescribed not only for

[page 310]

Ipswich School, happily established by the Lord Thomas, Cardinal of York, but also for all the other schools of the whole of England'. This seems to show that Convocation was only adopting what was perhaps already enunciated by Wolsey's legatine authority. The exclusive use of this grammar was later prescribed by the King in a proclamation, the date of which has never been exactly ascertained, first mentioned in a copy printed by Bartlet in 1542. So successful was the prescription that for thirty-four years this grammar, slightly revised in 1758 and re-christened the Eton Latin Grammar, reigned without a rival in the schools of England, and was only superseded by the Public Schools Latin Primer in 1867.

Another example of Henry's zeal for education was the strenuous attempt made, in ushering in the reform of the Church, to enforce the duty of promoting education on wealthy ecclesiastics. Through Thomas Cromwell, Privy Seal, Vice-gerent of the King in causes ecclesiastical, at a general visitation held in 1536, he put forward the following quaintly-worded injunction:

'And to the intent that learned men may hereafter springe the more, every beneficed man having yerely to dispend in benefices and other promotions of the church £100, shall gyve competent exhibition to one scolar', and for any additional £100 another scholar 'in the universitie of Oxford or Cambridge or some grammer scole'. The object is stated to be that after these scholars have profited in good learning they may be partners in their patrons' cure and charge as well in preaching as otherwise in the execution of their offices. But the lawgiver did not forget the State, for he adds 'or may otherwyse profite the common wealth with their counsell and wysdom'.

Henry VIII's chief work in education consisted in refoundation and improvement, not in creation of new schools, but he did it on a scale which entitles him to the praise of being, in a sense, the greatest of school founders.

It has been commonly assumed that in abolishing the monasteries he abolished a large number of schools, and a saying of an Elizabethan Speaker to the effect that 100 schools had disappeared has been cited as referring to monastic schools. This assumption is founded on the erroneous notion that the

[page 311]