[page 197]

IX

GENERAL SURVEY OF OTHER AREAS

IN previous chapters we have surveyed in some detail special areas. It is now proposed to travel more lightly over other districts, enumerating only the important facts and figures relevant to this study. In each case there are local considerations to be borne in mind, and sometimes there will be minor qualifications owing to special circumstances. From the foregoing pages it is obvious that the only intelligible method of interpreting the crucial parts of the 1918 Act - that is, the determination of the number capable of profiting by secondary education and the removal of economic barriers preventing those who are capable from taking advantage of such education - is to examine all children somewhere about the age of 11 years, and then make careful enquiries why scholarships offered are refused. If a broad and comprehensive test of merit is applied, the same for free-placers and fee-payers, it is then possible to discover how much capacity is being lost. At present some authorities have a common examination, some have different standards, some examine a selected number, others examine all. Some make close enquiries and give publicity to their examinations; others tread softly and assume they have cast their net sufficiently wide. This is not to assume that secondary education is for all, nor that such education should be entirely free, but that without such method and

[page 198]

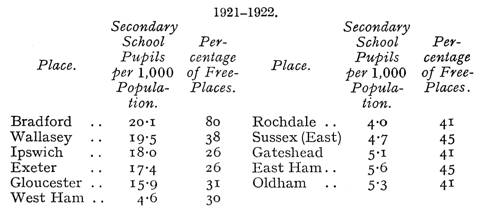

rough working basis it is impossible to make an accurate estimate of the needs of the locality. Not all areas with a larger number of secondary school pupils have also a large number of free secondary school pupils, as the following tables show:

TABLE LXXIX

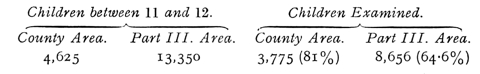

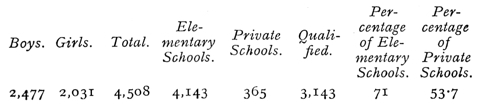

Middlesex is an area with a common examination for all entrants, and a uniform qualifying standard for the county. A further examination is held for a selected list of candidates, estimated in some places on ability, in others on the basis of double the number of available free-places. Any parent could demand the second examination, but very few did.

TABLE LXXX

TABLE LXXXI

TABLE LXXXI

[page 199]

TABLE LXXXII

Thus no less than 1,585 children, eligible on educational grounds of a very decided character, were not transferred. The district suffers from unequal accommodation and different intellectual standards. The Director also hints that there are other kinds of tests than that accepted by the Departmental Committee - namely, the likelihood of reaching the "first examination" standard by 16 or 17. In this district there used to be a large number of parents waiting to pay fees for their children; this is not so now.

The problems now are:

(a) Ability to pay fees.

(b) Ability to pay maintenance.

(c) Ability to sacrifice potential earnings.

In Middlesex there are not only the ordinary free-places, but others at reduced fees, as happens in one London school. It is pointed out that the only logical basis for free-places is the need of the district. The percentage of a previous year is a basis with neither scientific nor educational backing.

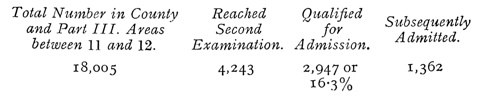

Manchester is also a city where there are available statistics, and some important facts emerge from them. Out of 20,000 odd children, there is a preliminary selection of 7,000; the parents of 3,000 will not allow the final test.

[page 200]

The actual figures appear below:

TABLE LXXXIII

The second examination is open to all who have gained 50 per cent, and whose parents are willing. Thus 4,130 children compete for 1,400 vacancies in municipal and central schools.

In 13 schools 100 per cent of eligible children gained 50 per cent or over.

In 33 schools 80 to 100 per cent of eligible children gained 50 per cent or over.

In 53 schools 60 to 80 per cent of eligible children gained 50 per cent or over.

In 75 schools 40 to 60 per cent of eligible children gained 50 per cent or over.

In 28 schools 20 to 40 per cent of eligible children gained 50 per cent or over.

In 5 schools below 20 per cent of eligible children gained 50 per cent or over.

It is of interest that 12 schools entered for the high schools only, and 52 for the central schools. Of the pupils 1,054 put the high school as first preference, and 1,826 the central schools. These facts can be put more concisely thus:

There were 4,130 children competing for 1,398 vacancies, of which -

(a) 2,014 children were competing for 470 high school vacancies.

[page 201]

(b) 2,786 children were competing for 928 central school vacancies.

From 19 schools 20 or more pupils went on to higher education (one school sent 31).

From 47 schools (5 provided and 42 non-provided) no pupil went on.

From 18 schools between 1914 and 1921 no pupil has proceeded to secondary education.

From 28 schools (11 provided and 17 non-provided) only one pupil went on.

Manchester Grammar School, which holds a somewhat similar position in Manchester as Bradford Grammar School in Bradford, accepted boys holding in order of merit the following places: 59th, 79th, 134th, 142nd, 165th, 176th, 215th, 382nd. Side by side with this last fact it must be remembered that of the first 25 boys, 10 applied for central school only.

A very bare recital of facts and figures is almost enough in a case like this. Sufficient is it to say that in Manchester about 8,000 children are selected every year by a first examination, and that 50 per cent of these could not go forward, even with a system of free secondary education, because their parents cannot afford it. What is required is maintenance and a greater variety of type of post-primary education.

Liverpool is another important centre of industry and trade, in some ways analogous to London. It has a dock area and a strong commercial bias. During the last five years there were 420 scholarships and 1,665 free-places given, and 321 departments from which the children might have come. There were 78 departments who did not nominate

[page 202]

a single child, 208 out of 321 did not win a scholarship, while 115 failed to secure a free-place. A member of the Education Committee points out that this is primarily due to economic and social conditions of the homes. Taking the three kinds of schools, the proportion per 1,000 of population sent on for free secondary education was as follows:

| % |

| Council Schools | 4.39 |

| Roman Catholic | 2.71 |

| Church of England | 1.79 |

There are 64 Council schools, who together won 295 scholarships and 1,080 free-places, but 6 schools won half the total. There are 43 Roman Catholic schools, who together won 81 scholarships and 377 free-places, but 5 schools won half the total. There are 53 Church schools who together won 41 scholarships and 199 free-places, but 4 schools won over half the total. A further subdivision would reveal one or two in each case who carried off a quite disproportionate number. If the 39 wards of the city are analysed, it appears that 8, with an average attendance of 37,133 children, sent on 1,224 children, and that the 31 others, with 81,242 children, had only 850 places distributed among them. At present it is not known how many children are capable of profiting, and it has been agreed that in future a general examination of all children shall be held. From visits in some of the poorest schools in Liverpool it was quite obvious that the parents did not contemplate any further education after the age of 14, but the masters assured me there were many boys who, with maintenance grants, could easily profit by secondary education.

[page 203]

The results of the admission examination in Birmingham show that nearly 60 per cent of the children who are offered admission do not accept it. The main reason is the inability or unwillingness to meet the cost of -

(a) Fees.

(b) Incidental expenses.

(c) Foregoing possible earnings.

It was decided to have a uniform fee of £8 for all secondary schools, with 40 per cent free-places and remission of fees (under income limits) up to 85 per cent of all pupils on the roll. Fees were not abolished, because it was felt that some people valued more highly what they paid for, and also because some parents might then keep their children away from the schools. These two objections are stated, because they are the chief arguments against free secondary education both in Birmingham and the country generally. Side by side with such objections must be put the facts of other authorities such as Cumberland, where the fall of admissions from 625 in 1919 to 414 in 1923 is attributed to inability of parents to afford fees, and the regulations that a child must stay until the age of 16.

In Wales there is the same diversity. For example, Anglesey divides the results of the examination into three classes - those with over 60 per cent, those between 50 and 60 per cent, those with 33 1/3 and 50 per cent - and a pass in the third class qualifies a candidate for entrance as fee-payer. Flintshire has a uniform examination for all school districts, and this is the only avenue for free-placers or fee-payers into municipal or intermediate schools. In Radnorshire the fee-payers' standard is 10 per cent less than that

[page 204]

for scholars. Swansea secondary schools are quite free, but there are fees at the intermediate schools. Thus, in Wales, where post-primary education is more accessible, there is much variation in subjects, examining board, age of entry, and standard of entry; there is overlapping and lack of continuity. It should be easier to make of education a continuous process where 90 per cent of the secondary school population are ex-elementary school pupils.

Bournemouth has a general test examination for all children between 10½ and 12 years of age, while Brighton frankly states that the preliminary examination there is an eliminating test. For the second examination, in 1922, 171 pupils qualified and sixty-nine scholarships were given. Lancashire for the three years 1922-1924 has undertaken a yearly review of all children of suitable age. The entrance for scholarship examination has increased from 3,020 in 1922 to an estimated 5,600 in 1925. The figures are as follows:

TABLE LXXXIV

The review is conducted by head teachers with the object of discovering suitable children for possible transference, and in 56 per cent of the cases graded tests, according to the age and attainment of scholars, were used. In Bury 290 out of 650 entering for the examination were reported unsuitable, the rest were offered secondary or central school places. In Burnley the percentage of retardation is estimated in 1923 as 16.6, and 1924, 12.3, varying in different schools from

[page 205]

12 to 60 per cent. But each year about 30 per cent of the children reached a qualifying standard for post-primary education, though only 6 per 1,000 population of Burnley children are in secondary schools. In Croydon it is stated that while a number of unsuitable candidates enter for the preliminary examination, not all of scholarship standard enter, it being quite understandable that in poorer districts many parents do not see their way to make provision for secondary education, even with the assistance of maintenance grants. Cumberland is also satisfied that quite an appreciable number of children of promising intelligence have not been sent forward, but adds significantly that it is not always the child that comes out top in a written examination who is possessed of the best qualifications.

Durham was one of the earlier authorities to size up the problem, and one of the difficulties it foresaw was on the administrative side. The elementary school code, the secondary school regulations, the regulations for junior technical schools, each laid down different amounts of square feet per child for accommodation. Also the salary basis further complicates the question. One has known schools where the transference of an extra half-dozen pupils to secondary education and consequent diminution in average attendance has made a reasonable difference to a headmaster's salary. In 1916 it was estimated that the children between 12 and 15 could be classified thus:

| % |

| Elementary schools | 64.2 |

| Secondary schools | 4.5 |

| Higher elementary schools | 1.1 |

| Left for work | 30.2 |

[page 206]

The striking figures are that only 4.5 per cent were in secondary schools, that 30 per cent were finished with day schools, and that 10 per cent of the total, actually in elementary schools, were below Standard V. Out of a total of 45,000, deducting the backward and those in higher elementary or secondary schools, there were 33,000 for whom account was necessary. Recognising that in the previous year out of 850 leaving secondary schools 231 left under the age of 15, and that 187 out of 270 leaving over the age of 17 were pupil teachers, the problem presented enormous proportions. Even after struggling to make secondary education increasingly free, only 6.3 per 1,000 population are in secondary schools today. There are no children under 11 years of age in these schools. It would cost well over two million pounds, on the basis of £75 a place, to give secondary education to all in Durham. The suggestions made in the survey of 1916 before the Fisher Act were for "higher tops", with classes of not more than thirty-five, specialist teachers on secondary school scales, and an allowance per head for books, apparatus, stationery, etc. The survey closed with this statement: "It was far from the intention of our educational legislators that an insignificant percentage only of promising students from the elementary schools should be enabled to climb successfully the rungs of secondary education. This has been the result. The remedy for this defect must clearly take some form of educational overlapping."

In answer to an enquiry from the local Trades Council, the East Ham Committee said that, with the exception of seventeen boys, all who qualified in the examination and whose parents desired admission had been found a place.

[page 207]

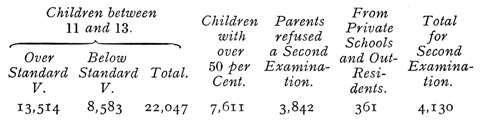

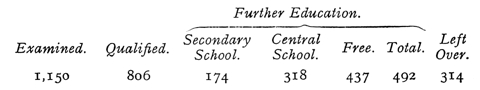

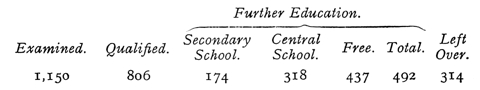

In 1924 the following were the relevant figures for the examination:

TABLE LXXXV

Gloucestershire in 1923 held a compulsory examination in seventy-seven departments; in 1925 in all departments. Though this county is above the average for English counties, due in some measure to the better inheritance of grammar scholars from the middle ages, over 30 per cent of the pupils come from private schools, and 11 per cent are under 11 years of age. Huntingdonshire states that in view of the fact that secondary schools are now supported by public money to such a large extent, while the fees paid by parents have become relatively unimportant, the willingness on the part of a parent should not of itself entitle a pupil to admission, and they therefore propose to make a qualifying examination for all. Northumberland now has a common examination for scholars and fee-payers. After a most interesting and detailed test of over 13,000 children between the ages of 11 and 12, it was discovered that over 50 per cent are normal or average, a further 20 per cent are advanced, while 1 per cent are of very high intelligence. The rest, which amounts to 24 per cent, must be classed as backward, though in varying degrees. Nottingham has a common examination for all children in Standard IV or above, between 11 and 12, but has to recommend further free and assisted scholarships, based on evidence of need. Somerset, in order to make more

[page 208]

widely known the advantages of free-places, and to secure entry of all suitable candidates, has decided that all children between 11 and 12 shall be examined, shall take the county free-place examinations, while East Sussex has amalgamated the county scholarship and free-place examinations. West Ham have become conscious that their test is not qualifying, but competitive, and it has been decided that not merely the names of candidates recommended be published, but also the applicants, whose standard of work is sufficiently high to warrant inclusion, if no limit to the number of awards existed. There are 13,000 pupils between 10 and 11, and 6,000 between 12 and 13 years of age. Although only 1,275 sat for the examination, a common preliminary and qualifying examination was not accepted, owing to the unnecessary expense and labour entailed. It would appear difficult to carry out the Fisher Act with any accuracy until some such review had been undertaken. In Wiltshire 188 awards, including local charities, were made from 1,227 applicants, 1,207 of whom had passed the county eliminating test. Of the 1,039 left over, seventy-two entered as fee-payers. In 1924, two years later, 277 obtained at least 60 per cent, and did not proceed to a secondary school.

An interesting commentary is offered by Newcastle through the words of a Director: "The effect of this section of the Act (i.e., the crucial part on which this book dwells) will be to destroy the present competitive system of scholarships and to put in its place a system which the prospective candidate for higher education will need to show due qualification, and not necessarily pre-eminence among his fellows"; and again: "I am of the opinion that a system of secondary

[page 209]

schools, under which large numbers of children may claim free admission, and under which large numbers may claim admission proportionate to their means, while other children pay full fees, cannot continue. ... As, however, every child is entitled to education in an elementary school up to 14 or 15, a general transfer of all normal children to places of higher education at or about the age of 12 would appear to serve as a necessary concomitant, a system of free further schools."

Before leaving this general survey and indicating the tendencies they reveal, mention of two places who have experimented further into grading of schools should be made. The one is Carlisle and the other Leicester. The main feature of the latter is the grading of pupils from 11 years of age, when an examination is taken by all children, except certain backward ones whom head teachers need not enter. Those reaching a prescribed standard and whose parents sign a four years' agreement go to secondary schools, as free-placers or fee-payers; others are drafted to an intermediate or central school; all others, including the exempted, are drafted to senior schools. The junior schools range from 7 to 11 years and are mixed. In the junior as in the senior schools there is duplication of classes; there may be three or four parallel classes moving at various speeds through the schools. Transfer to a parallel class is possible during the school year, and to a different parallel at the end of the year. The Roman Catholic schools are outside the scheme, though Church of England schools have their own junior and senior schools. Parental difficulty, due to the greater distance some children have to walk, has been overcome

[page 210]

while the staffing problem presented few obstacles. No compulsion is exercised for intermediate school pupils to remain at school after 14 plus, though they may take the school certificate and stay a fourth year; indeed, a few have done so. About 50 per cent of an age-group enter for the examination, and as not more than 20 per cent are subnormal about 30 per cent more should enter. Of about 4,000 children of the 11-year age-group, about 1,500 passed the qualifying examination for entrance to an intermediate school. Between 400 and 500 qualify as fee-payers or free-placers for secondary schools, and an average of 400 actually go forward. The great merit of these preliminary parallel classes is the easier task of transference. The curriculum may be varied to suit special aptitudes, and at 11 plus the general examination, dividing pupils into three classes, with later transference from senior schools to intermediate and intermediate to secondary where it is desirable, becomes at once more elastic and more selective.

Carlisle has a scheme resembling Leicester in many points. Junior schools are for all up to the age of 11, except that there is no infant department. The junior merit examination then takes place, and pupils go either to senior schools up to 14, to central schools up to 15 or 15½, or to the old grammar school and girls' high school. It is proposed that the senior schools become central schools as soon as possible, and later secondary, and that the central schools become secondary. In a word this is gradual secondary education for all. Junior technical schools were turned down as being too rigid in code, but all senior schools have workshops and handicraft rooms. The central schools have so far worked

[page 211]

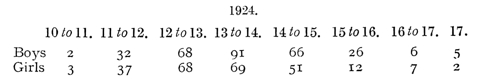

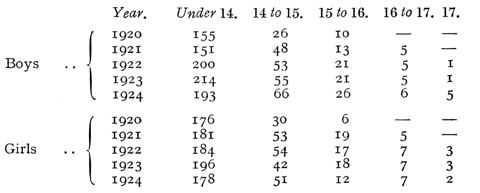

under the elementary code, but a few children have taken the matriculation and senior Oxford examinations. Below are two tables showing the age-groups at central schools:

TABLE LXXXVI

TABLE LXXXVII

TABLE LXXXVII

BEYOND 14 OVER A PERIOD OF YEARS

From August 1 these two central schools will become secondary schools, and as the above figures show there has been a progressive lengthening of school life, until it has become at least as long as certain secondary schools in other parts of the country. The senior schools pay particular attention to practical and individual work and cross classification of pupils for various subjects, but there are no parallel classes as in Leicester. There is obviously much to discuss in these two experiments; the motives, as always, which prompted them are mixed. For the reorganisation of existing schools is a scheme which combines economy

[page 212]

with a certain efficiency. The Carlisle plan is definitely working towards secondary education for all at a future date. With regard to raising the school age, premises and staff are assured, but there are questions as yet unanswered, such as exemptions and maintenance, which immediately raise controversy. In the Leicester scheme it is frankly admitted that the intermediate scholars are mostly capable of profiting by secondary education, but "for various reasons" are unable to proceed to secondary schools. Inasmuch as "various reasons" are mainly economic, the problem still remains. In Carlisle much of the success is due to the bringing together of teachers, parents, rate-payers, and all concerned parties, and informing public opinion. The central schools were started before the war voluntarily, and a graduate from Cambridge was put in charge.

[page 213]

APPENDlX

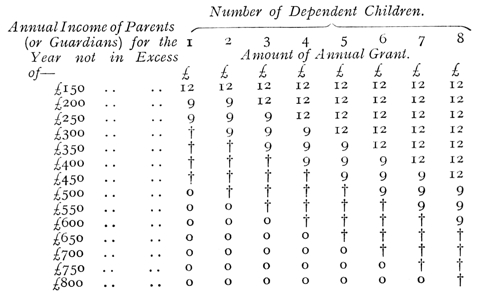

THE following Schedules show the effect of the income limits as regards eligibility and maintenance grants.

The number of children means the number inclusive of the scholar in each case. 0 means ineligible for scholarship or free place; † means eligible for free place only.

SCHEDULE No. 1

SECONDARY SCHOOLS: JUNIOR TECHNICAL SCHOOLS

Junior awards. - Amount of annual grant payable up to the end of the school year in which the age of 14 years is attained.

Trade scholars who commence their training in March or April and are 14 years of age by July 31, will receive grants under Schedule No. 2 as from August 2.

[page 214]

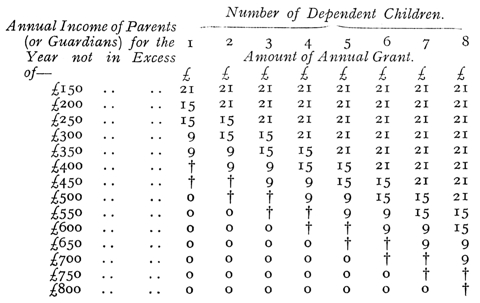

SCHEDULE No. 2

SECONDARY SCHOOLS: JUNIOR TECHNICAL SCHOOLS

Junior awards. - Age 14+ to lapse

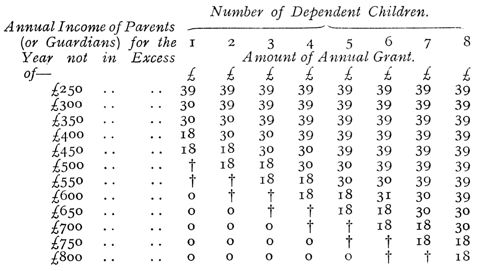

SCHEDULE No. 3

SCHEDULE No. 3

SECONDARY SCHOOLS: TECHNICAL INSTITUTES, ETC

Intermediate awards. - Age 16+ or 17+ to 18 or 19

[page 215]

These tables may be extended when the number of children exceeds eight by increasing the income limit by £50 for each additional child. The expression "child" means a son or daughter who (1) is under school age, or (2) is pursuing his or her education as a full-time student.