[page 393]

PART III

VISITS TO VARIOUS INSTITUTIONS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

Your Commissioners having in the previous portion of their Report described the educational and industrial establishments which we visited on the Continent, now proceed to notice some of the more important kindred institutions which we have inspected in the United Kingdom. As most of these are sufficiently well known, we have dealt briefly with this branch of our subject.

The following is a list of the towns and institutions treated of:

London School Board.

I. University College.

II. King's College.

III. Normal School of Science, South Kensington, and Royal School of Mines.

IV. Museum of Practical Geology.

V. National Art Training School.

VI. Science and Art Department, as to Examinations.

VII. City and Guilds of London Institute.

VIII. Polytechnic Young Men's Christian Institute.

IX. Royal Indian Engineering College.

X. Royal Naval College, Greenwich.

XI. Crystal Palace School of Engineering.

XII. Oxford.

XIII. Cambridge.

XIV. Manchester.

XV. Liverpool.

XVI. Oldham.

XVII. Barrow-in-Furness.

XVIII. Birmingham.

XIX. Leeds.

XX. Sheffield.

XXI. Bradford.

XXII. Keighley.

XXIII. Saltaire.

XXIV. Nottingham.

XXV. Bristol

XXVI. Bedford.

XXVII. Kendal.

XXVIII. Glasgow.

XXIX. Edinburgh.

XXX. Ireland - Dublin, Cork, Belfast, and the West of Ireland.

LONDON

London School Board - Instruction in Elementary Science. Before passing on to the institutions for scientific, art, and technical instruction, it may be well to state briefly the steps which have been taken by the School Board for London for introducing instruction in elementary science into their schools.

In addition to the object lessons given in the infant schools, the School Management Committee have decided* that elemen-

*See Circular, October 30, 1882.

[page 394]

tary science shall be taught throughout the boys' and girls' departments, in place of the object lessons hitherto given, and their instructions to the teachers, on object lessons, have been modified accordingly.

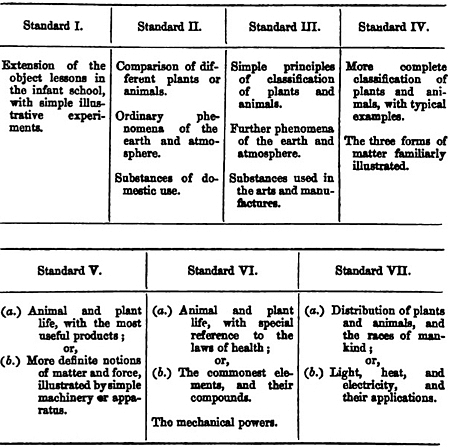

The following is suggested by the School Management Department as a model scheme, but teachers have full liberty to vary it according to their tastes and acquirements:

A more detailed description of the courses on physics, mechanics, chemistry, and physiology, has also been prepared by the Board.

Moreover, courses of instruction in elementary science, have been established by the Board for the central instruction of pupil teachers.

The School Board for London has not as yet established any higher elementary or graded schools, such as exist in Manchester, Sheffield, and elsewhere, having laboratories for the practical teaching of science; nor have they adopted the excellent system, which the Commissioners found at work in Birmingham and in Liverpool, of employing a science demonstrator, who teaches the subjects with practical illustrations in the various elementary schools.

[page 395]

I. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, LONDON

Although the endowments of this college are insignificant compared with those of the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, and of many modern institutions, yet University College has always stood in the front rank with respect to its scientific teaching, and the recent erection of extensive and well-fitted chemical, physiological, and engineering laboratories, shows that the spirit which has animated the authorities of the college in the past has not suffered diminution.

The Commissioners first inspected the new chemical department under the direction of Professor Williamson, F.RS., where every convenience for practical work and research is found. The laboratory contains 45 working places, and the block of new buildings, including the physiological section, cost £40,000. The department of applied chemistry under Professor Charles Graham, is of recent foundation; lectures are given on the alkali manufacture, baking, brewing, &c. The practical work in this laboratory is made as far as possible to bear on the various industries. The City and Guilds of London Institute contributes £200 per annum to the maintenance of this department.

The engineering department under the charge of Professor Kennedy, was next visited. The laboratory contains a large testing machine, capable of working up to 45 tons. In this department there are 60 students, and the manual work done is confined to the preparation of small specimens for mechanical testing. Professor Kennedy does not attach much value to teaching young men practical work in the school; he is of opinion that they should be taught to draw well, and should be made thoroughly acquainted with the principles of the machines with which they will hereafter have to work. He thinks that it would be a great advantage, if all young men about to become engineers could take part in the practical testing of the properties and strength of materials.

Professor Kennedy is engaged in private practice as a consulting engineer, and the students are often employed on the investigations which he is called upon to perform. The City and Guilds Institute contributes £200 annually to this chair also.

In the physical department under the care of Professor Carey Foster, F.R.S., the tuition is chiefly of a theoretical character, there being very insufficient means of giving practical laboratory instruction.

The Slade Art School, under the direction of Professor Legros, is another department of University College. The building for this department is complete and commodious, containing studios for drawing from the life and the antique, as well as lecture rooms, where lectures on anatomy, the science of perspective, the chemistry of colours, &c. are delivered. The school is in a very flourishing state, and is open to female as well as to male students.

[page 396]

Attached to University College is a very successful high class modern school, under the head-mastership of Mr. H. Weston Eve, containing 600 boys. Considerable attention is paid in the school to the teaching of science, practical laboratory instruction being given in Chemistry by Mr. Orme, (working places being provided for 60 boys), and in Physics by Mr. J. J. Walker.

II. KING'S COLLEGE, LONDON

The Commissioners were received by the principal of the College, the Rev. Canon Barry.

Similar remarks as to the value of the scientific and technical instruction, apply to King's as to University College.

A remarkable feature of this institution are the workshops connected with the engineering department. In these, the students go through a series of exercises in mechanical work. The college course lasts for nine terms, and engineer students passing through this, are said to shorten their apprenticeship by two years. The direction of this department is under Professor Shelley, and the practical instruction is given by Mr. Walker. The course of instruction has more of a workshop character than that at University College. The carpenters' and mechanical shops and smithy are open under certain regulations to the boys from the school attached to the college. In the joiners' shops they learn to make the common joints of carpenter's work, and the fitting of doors and windows, whilst in the engineers' shop they learn wood and metal-turnings chipping, filing, and surfacing.

The chemical laboratories under Professor Bloxam contain, in the general division 62 working places, and in the advanced 20. There is a distinct department for photographic work under Mr. Thomson.

The Wheatstone Physical Laboratory is a noteworthy feature of the physical department, under Professor W. G. Adams, F.R.S. It is large and well arranged for practical work, and a considerable number of students avail themselves of it. A large collection of physical apparatus and several rooms for special experiments are also found in this section of the college. The department of applied fine ' art is under Professor Delamotte, and in this an attempt is made to apply art teaching to industrial purposes, and students are engaged in designing for china and for woven fabrics.

The mechanical drawing department is under the charge of Professor Glenny.

[page 397]

III. NORMAL SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND ROYAL SCHOOL OF MINES, SOUTH KENSINGTON

The Commissioners visited the Normal School at South Kensington, and were received by the Registrar, General Martin, who accompanied them over the building.

This school, which was reorganized in 1881,* gives systematic instruction in mathematics and mechanics, physics, chemistry, biology and botany, geology and mineralogy, agriculture, metallurgy and assaying, elements of astronomical physics, practical geometry, and mechanical and freehand drawing. Mining is taught at the Museum of Practical Geology in Jermyn Street, but forms part of the Normal School. The Normal School is primarily intended for the training of science teachers, and the instruction of students of the industrial classes, selected by competition in the annual examinations of the Science and Art Department; but other students are admitted on payment of prescribed fees. The students may be (1) occasional students and (2) regular students who are preparing for the associateship of the school, and pass through a prescribed course extending over 3 to 3½ years. The instruction for the first two years for all the associate students is the same, and includes mechanics and mathematics, physics, chemistry, elementary geology, astronomy, mineralogy, and drawing. The student then elects to take up one of the following divisions, to which the remainder of his course is directed: viz., for the title of Associate of the Normal School of Science, I. Mechanics, II. Physics, III. Chemistry, IV. Biology, V. Geology, or VI. Agriculture; and for title of Associate of the Royal School of Mines, either VII. Metallurgy, or VIII. Mining.

There are 12 exhibitions each of the value of £50 per annum tenable at this school, and continuing during the course of time (3 to 3½ years) necessary for the preparation for the associate ship examination. The exhibitioners have also free admission to the lectures and laboratories. Three or four are vacant each year, and are competed for at the May examinations of the Science and Art Department. Six free studentships are also similarly annually competed for. These correspond to the exhibitions, except in so far that they carry no money grant.

Free instruction is likewise given to local exhibitioners, who hold scholarships of the value of £50 per annum, half of which sum is subscribed by the locality, and half by the Department. There are also royal scholarships, four of £15 for first year students, and two of £25 for second year students.

About 50 science teachers, or students intending to become teachers, also receive free instruction, and in addition are paid the railway fare to London, and receive a maintenance allowance of 21s a week whilst under instruction.

*For history of the school, see Prof. Huxley's evidence (Answer 3070.)

[page 398]

During the summer vacation, short courses of lectures, extending over three weeks, are given to science teachers, about 200 in number, who are aided by the Department in the payment of the expenses of the journey to, and residence in, London during the progress of the course.

Courses of popular evening lectures for working men are also given by the professors.

The Commissioners first visited the Metallurgical Laboratory which had recently been fitted up in the basement of the building. The Chemical Laboratories under the charge of Professor Frankland were inspected, and also the Physical Laboratory of Professor Guthrie and the Physiological Laboratory under Professor Huxley. The Commissioners had conversations with the professors, on the system of science teaching adopted in the school.

Professor Huxley, the Dean of the School, explained the methods of practical and theoretical instruction given under his guidance in the department of biology, which includes an important museum and a large collection of preparations and diagrams arranged for the special purposes of study. Pure and applied geology under Professor Judd forms an important feature of the science instruction, and the students are brought into close contact with the subject by the microscopic preparation and examination of rock sections and other practical geological work. Professor Guthrie explained the way in which he had introduced laboratory work in physics; every student having to construct certain simple physical apparatus. Professor Chandler Roberts stated that in his department (that of metallurgy), there were 30 working places. Since coming to South Kensington he had had a large addition of students, and there were now 40 under instruction, and it needed much ingenuity to arrange the places for them. In the chemical department the numbers have slightly fallen off.

IV. MUSEUM OF PRACTICAL GEOLOGY AND ROYAL SCHOOL OF MINES

On the occasion of their visit to the Museum in Jermyn Street, the Commissioners were received by Professor Warington Smyth, F.R.S., and Mr. Rudler, the curator. Since the transfer of the School of Mines to South Kensington in 1881, the practical science teaching, except in the caÇe of mining students who take part of their instruction here, has virtually ceased. Evening science lectures for working men take place during the session; the charge for admission to each course of lectures is 6d. There is a good library, a small chemical laboratory, a lecture theatre, and the necessary class-rooms.

The geological collection first known as the Museum of Economic Geology, was transferred to Jermyn Street from Craig's Court in 1851. The museum was designed to illustrate

[page 399]

mainly the geology of Great Britain and Ireland, and to show the applications of geological science. It contains specimens of minerals, including the ores of the useful metals, and models representing metallurgical processes. The various arts connected with the mineral resources of the country are illustrated by specimens showing varieties or peculiarities of manufacture. An excellent historical collection of English pottery and porcelain has been added, and there is a very complete series of English building stones.

The collection of models of mines, mining tools, and mining machinery is very extensive. All the varieties of safety lamps are shown.

The Mining Record Office, which was formerly situated at Jermyn Street, was transferred to the Home Office in 1882.

The Offices of the Geological Survey of Great Britain are also at the Museum.

V. NATIONAL ART TRAINING SCHOOL

The School of Design which, in 1853, was removed to Marlborough House from Somerset House, has been established since 1856-7, at South Kensington, as the National Art Training School.

An important change has taken place in the conduct of the school since 1871, when, in order to fulfil more efficiently its primary object of training teachers, an entrance examination was imposed. In the year 1880-1 there were 128 students (94 males and 34 females) attending the school without paying fees, 47 students were admitted on payment of half-fees, and from 759 students (359 males and 400 females) the sum of £3,022 was received in fees. The course of instruction includes 23 stages, in the highest of which, stages 22 and 23, the student takes elementary and applied design.

Certificates of competency to teach the subjects comprised in these various stages of instruction, are given to candidates who pass the necessary examinations. These are -

(a) The preliminary or art teacher's certificate.

(b) Art certificates of the third grade.

The Commissioners, accompanied by the principal, Mr. Sparkes, inspected the various class-rooms, and examined the work in progress. The more advanced students draw and model from the antique and from the life. We were present at a lecture by Mr. Stannus, on decorative art; and, on a subsequent visit, when we were accompanied by the Director for Art, Mr. T. Armstrong, we were shown the designs for industrial purposes made by the students of the training class, among which were specimens of designs for metal work, wood carving, goldsmiths' work, pottery, and the interior decoration of buildings. These designs are worked out in competition among the students.

[page 400]

VI. EXAMINATIONS UNDER THE SCIENCE AND ART DEPARTMENT, SOUTH KENSINGTON

Examinations in art, in connection with the Science and Art Department, date back to 1853, though the existing comprehensive plan of annual examinations was not established until 1857. In that year, 12,509 students were instructed in local schools of art, and 396 in the Central Training School, and through the various agencies connected with the Department, 43,212 children in elementary and other schools were taught drawing. No general system of examinations in science was formulated until 1859, when the number of subjects, on which payment could be obtained, was limited to six. In May 1861, when the first general and simultaneous science examination was held, there were 38 classes with 1,330 pupils, besides some 800 pupils in classes not under certificated teachers.

In the year 1882, there were in all 909,206 persons receiving art instruction in connection with the Department, and 68,581 students in science, in 1,403 science schools, with 4,881 classes.

The Examinations in Art are of three grades, the first grade being intended for children attending the elementary school, the second grade for the pupils of secondary schools and the students of art classes and schools of art, and the third grade is applicable for teachers or art masters.

Science Examinations are held in 25 subjects; the examinations take place in May, and are divided into three stages; the "elementary", "advanced", and "honours". In each stage there are two grades of success.

On receipt of proper demands from local authorities, papers, both for the science and art examinations, are forwarded from South Kensington to the centres where the examinations are conducted. The worked papers are sealed up directly after the examination, and forwarded to London. On the result of these examinations, prizes and scholarships are awarded to the successful students, and money payments are made to the local committee, which vary in accordance with the degree of success attained by the students, and with the nature of the subject.

The total payments in the year 1882-3, on account of science schools and classes, grants, prizes, etc., was £45,376 0s 6d, and for success in art the amount was £67,354 10s 6d.

The total expense of the Science and Art Schools is returned at £155,367 5s 4d for the year 1882-83, exclusive of the staff of the department, who received £8,898 4s 10d.

[page 401]

VII. THE CITY AND GUILDS OF LONDON INSTITUTE

This Institute has been established by the City Livery Companies, for the purpose of providing and encouraging education adapted to the requirements of all classes of persons engaged, or preparing to engage, in manufacturing and other industries.

With this object the Institute subsidises existing educational establishments, which, in the opinion of the Council of the Institution, are providing sound technical instruction, and which would possibly languish except for external aid.

It also encourages, in the principal industrial centres of Great Britain, the formation of evening classes, in which workmen and foremen, engaged in their several factories during the day, receive special instruction in the principles of science, in their application to the processes with the practical details of which they are already familiar.

It aims at establishing and maintaining in the Metropolis model technical schools, to serve as types of other schools to be founded and supported by local efforts in provincial towns; and, lastly, it is erecting a Central Institution, corresponding to some extent to the great Polytechnic Schools of Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, and to the École Centrale of Paris.

With this varied programme, the City and Guilds of London Institute is assisting in the professional instruction of all classes of persons engaged in industrial operations, of artisans, apprentices, foremen, managers of works, manufacturers, and technical teachers.

The Council of the Institute have no intention of interfering with any existing social institution, such as apprenticeship, or any other relationship between employer and employed, but aim only at supplying the want of further instruction which is everywhere felt to exist, by supplementing, and by preparing pupils more thoroughly to profit by, workshop training.

For the establishment of technical classes in the Metropolis and in provincial manufacturing towns, the Institute has granted for a period of years the following annual subventions:

£400 to University College, London.

£400 to King's College, London.

£350 to Horological Institute.

£250 to School of Art Wood Carving.

£300 to Firth College, Sheffield.

£300 to University College, Nottingham.

£200 to Technical School, Manchester.

In addition to these annual grants, it has given £700 for the establishment of a Technical School in Leicester, as well as £200 to Nottingham, and £100 to Manchester for the purchase of mechanical appliances, besides other smaller grants.

[page 402]

In nearly all the large manufacturing towns, evening classes in Technology, as distinguished from the Government classes in Science and Art, are being assisted by the Institute. The work done by the students of these classes is inspected and examined by the Institute, and on the results of the annual examinations, certificates and prizes are granted, which are beginning to be regarded as diplomas of proficiency, and are said to enable operatives to obtain better employment and higher remuneration. These evening classes have already become, and are likely in future to become still more, the nuclei of technical colleges, mainly supported by the towns in which they are situated, but connected with, and affiliated to, the City and Guilds of London Institute, by means of its examinations and superintending influence.

According to the Programme of Technological Examinations for 1883-84, examinations are held in the following subjects:

1. Alkali and allied branches.

A. Salt manufacture.

B. Alkali manufacture.

C. Soap manufacture.

2. Bread-making.

3. Brewing.

4. Distilling

A. Coal tar distilling.

B. Spirit manufacture.

5. Sugar manufacture.

6. Fuel.

7. Oils, colours, and varnishes, manufacture of.

8. Oils and fats, including candle manufacture.

9. Gas manufacture.

10. Iron and steel manufacture.

11. Paper manufacture.

12. Pottery and porcelain manufacture.

13. Glass

14. Dyeing -

A. Silk.

B. Wool.

15. Bleaching, dyeing, and printing of calico or linen.

16. Tanning leather.

17. Photography.

18. Electro-metallurgy.

19. Textile fabrics, manufacture of -

A. Cloth.

B. Cotton.

C. Linen.

D. Silk.

E. Jute.

20. Lace manufacture.

21. Weaving and pattern designing.

22. Electrical engineering -

A. Telegraphy.

B. Electric lighting and transmission of power.

C. Electrical instrument making.

[page 403]

23. Metal plate work.

24. Plumbers' work.

25. Silversmiths' work.

26. Watch and clock making.

27. Tools -

A. Wood working.

B. Metal working.

28. Mechanical engineering.

29. Carriage buildmg.

30. Printing.

31. Ores, mechanical preparation of.

32. Mine surveying.

33. Milling (flour manufacture).

34. Carpentry and joinery.

These examinations were originally established by the Society of Arts, but were subsequently taken over and considerably modified and developed by the City and Guilds of London Institute. In 1879 the number of candidates was 202, and the examinations were held in 23 different places. In 1883, 2,397 candidates presented themselves from 164 centres in different parts of the United Kingdom.

The Finsbury Technical College, which was opened on 19th February 1883, has been erected, at a cost of about £36,000, to serve as a model trade school for the instruction of artisans and of other persons preparing for intermediate posts in industrial works. It consists of a school of applied science and art. There is a day and an evening school. The latter provides systematic instruction for those who are engaged in the staple industries of the district, including cabinet-making; and in the applications of chemistry, mechanics, and physics, to special trades, such as spirit rectification, mechanical engineering, electric lighting, &c. An approach has been made to the establishment of a relationship between this College and the principal middle class schools of the Metropolis, by the award to selected pupils from these schools of exhibitions enabling them, without payment of fees, to receive in the College scientific and technical training, fitting them for various occupations and industries, as well as for higher technical instruction.

The subjects taught comprise mathematics, pure and applied, practical mechanics, chemistry, physics, electrical technology, freehand, model, and machine drawing, workshop practice, French , and German; and in the evening additional classes are held in carpentry and joinery, metal-plate work, bricklaying, drawing, painting, modelling, and design.

The South London Technical Art School, situated in the Kennington Park Road, provides instruction for artisans engaged in various industries in which art aptitude is indispensable to success. The courses are for evening and for day students, for men and women. The subjects of instruction include drawing, modelling and painting from life, wood-engraving, china-painting, enamelling, and design.

[page 404]

The Central Institution in the Exhibition Road, now in course of construction, is intended to give to London a first-class college in which technical teachers for the provincial schools may be educated, and in which those who are to be engaged in the superintendence of great industrial works may receive their preliminary training. The establishment of this Central Institution will, it is hoped, render unnecessary the recourse to foreign countries (where similar institutions already exist) for the technical instruction of managers of works, engineers, and industrial chemists, and will be welcomed by manufacturers, who feel the want in London of some such institution, in which their sons who are to succeed them can obtain as good an education as at Paris, Zurich, Munich, or Berlin. Just as the École Centrale at Paris is about to be removed to the immediate neighbourhood of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, in order that the students may be near to the collections of machinery and other industrial objects which the Conservatoire contains; so the Central Institution of London is built near to the Science Schools and National Museums of South Kensington. Besides giving to the Metropolis a Technical High School or Technical University for advanced instruction in the applications of science and of art to industrial operations, the Central Institution, as a training school for teachers, as a focus for uniting the different technical schools now in existence, and as a centre for the dissemination of technical knowledge, is expected to be the means of increasing the efficiency of every department of the Institute's work.

It is estimated that the Central Institution, with its fittings, &c, will cost about £96,000, of which sum the Council of the Institute have been able to provide about £75,000 by accumulated savings and by grants from several of the Companies as indicated in the report. There is a deficit of about £20,000 now needed for fittings, furniture, and apparatus, which the Council have at present no means of supplying.

The Central Institution. The foundation column of the Central Institution was placed by His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, President of the Institute, on the 18th July 1881.

The building has a frontage of 300 feet in the Exhibition Road, on the opposite side to the South Kensington Museum, and closely adjoining the Natural History Museum, designed by the same architect, Mr. Alfred Waterhouse, A.R.A., of London. The exterior Is of a semi-classic character, and the arms of the principal manufacturing towns in the United Kingdom are displayed in strong relief upon its front.

It is, for the most part, five stories in height. In the basement are physical laboratories and mechanical workshops, three very large shops at the back being top-lighted. The entrance-hall is in the centre of the building, and leads to the great corridor which stretches from one end of the building to the other. Mechanical class-rooms, physical class-rooms, a museum for industrial apparatus, and a room for the teaching of mathematics are on three floors. There are also at the back of the building two

[page 405]

large lecture-theatres, lighted principally from the sides; one being for chemistry and the other for physics and mechanics.

On the first floor, over the entrance, is a large reading-room and library, with experiment rooms and class-rooms on each side of it. The offices for the administration are towards the north end of the building, terminating in the council-chamber, a handsome apartment, on the walls of which it is proposed to emblazon the arms of all the Livery Companies. On the second floor an art museum occupies the principal position in the centre of the building, with class-rooms and lecture-rooms on each hand. On the third floor, above the art museum, is a large room, 67 feet by 35 feet, with a fine semi-circular roof, to be used as a museum of technology. At one extremity of the building is a refreshment-room for students and others engaged in the building. At the opposite end is a large special laboratory adjacent to the general chemical laboratory, underneath which are two additional laboratories for special purposes.

There is space for an additional wing at the south end of the building, corresponding to that at the north end, which contains the chemical department and the lecture theatres.

The scheme for the organization of this institution will be found in the Appendix, Vol. IV.

The Technical College, Tabernacle Row, Finsbury, London. This institution, founded by the City and Guilds of London Institute, gives technical instruction, both day and evening, of a character suited to the requirements of artisans and others. Practical laboratory work in the subjects taught, forms a special feature of the system of instruction.

A complete course of instruction has been drawn up for the day students and for those attending the evening classes. The students can enter into any one of the following departments:

(1) Mechanical engineering.

(2) Electrical engineering.

(3) Industries involving applications of chemistry,

(4) Building trades.

(5) Applied art industries.

There are at present about 100 students attending the day school, and upwards of 600 students attending the evening school. The fees for the complete course of day instruction are at present as follows:

Annual payment, £9 in one sum, or £10 in three instalments. For the evening courses the fees range from 5s to 30s.

The course extends over two years, and it is proposed to give certificates to those students who go through the entire course satisfactorily.

Evening Instruction. The Commissioners visited this institution and the adjoining Middle Class School in Cowper Street on two occasions. They were met by Mr. W. P. Sawyer and Mr. Owen Roberts, two of the Honorary Secretaries, and some members of the committee, and inspected, in the first instance, the evening classes of the college. They were introduced to

[page 406]

Professor Ayrton, the teacher of physics and electricity, who conducted them over the various rooms in his department, eight of which are devoted to the laboratory work of the students.

One of these contains dynamo-machines, worked either by the main steam engine of the building or by a gas engine in the room. There is one large Edison dynamo-machine used for lighting the building, and students were engaged in making original experiments on some of the others. The second room is used for experimenting on accumulators, taking photometric measurements of electric lamps, &c. The third room is fitted up for delicate experiments, such as measuring the insulation and capacity of submarine cables, the instruments standing on pillars carried up from the basement. These three rooms are all used by second and third year students of electrical engineering.

The fourth and fifth rooms are fitted up for an organized series of experiments for first year students of electrical engineering; one of the rooms being for experiments in current electricity, and in static electricity. The peculiarity of the arrangement adopted is that each experiment has all the apparatus required for performing it ready in position, together with printed instructions. The students work in groups of three. This arrangement enables the very large numbers, who only come to the laboratory for a couple of hours at a time, to work together, and to complete, or nearly complete, one experiment during that time, which would be quite impossible if the students had to search for the necessary apparatus, resistance coils, batteries, &c., and to fit them up. The instruments needed for each experiment, completely fitted, are mounted on a board, which can be taken into the lecture room for use during the lectures. The sixth room, which is a small one, is fitted up for plotting curves, recording the results of experiments. The seventh room is used for experiments on heat, and the eighth is fitted up as a workshop for the manufacture and repair of physical apparatus, where a skilled workman is constantly engaged.

The Commissioners found students working in four of these rooms, which are more or less completely fitted with apparatus. The remaining rooms were not occupied, as the apparatus had not as yet been obtained for furnishing them.

The basement is well lighted, all the walls being lined with white glazed bricks. The first floor, which is very lofty, contains two large lecture theatres, each capable of seating 200 students. They are so arranged that the line of seats rises in the form of a curve, giving every student a good position for seeing the experiments of the lecturer. The black-boards behind the lecture table are so balanced as to be capable of being moved up or down with the least possible effort. The building and class-rooms throughout are lighted by means of Edison's incandescent lamps, but Siemens' gas lamps pave been provided in some parts of the building.

[page 407]

The chemical laboratories are on the second floor. Here the Commissioners were introduced to Professor Armstrong, who, explained the considerations by which he had been guided in the planning of the laboratory. The room is divided into two parts by double glass screens, between which are the arrangements for the supply of sulphuretted hydrogen for the use of the students, the elementary and the advanced. The former contains 43, and the: latter 51, working places, each of which, however, has two drawers and two cupboards, and is, therefore available for two students working at different times. The entire bench is covered with a hood, at the top of which are openings at intervals communicating with a chimney in which there is a powerful draught, produced by means of the waste heat from the boilers, so that all gases and vapours, given off in the experiments, are said to be drawn away into the chimney, and it is contended that by these means the laboratory is kept free from smell. The flues pass downwards from the benches, and along the floor.

Besides the Professor's and assistants' rooms, a class room, a balance room, two store rooms, the large lecture theatre, and preparation room, several rooms are provided for the use of more advanced students, and those engaged upon special work.

Professor Armstrong stated that the practical course is somewhat different from that of most chemical schools, the object in view being to teach the main facts and principles of chemistry, and to lead the students to observe correctly, and to reason from experiment, rather than to make them highly proficient analysts. It is thought that this system is best calculated to prepare them to carry on with intelligence those manufacturing operations which involve applications of chemical knowledge. It is intended that students who distinguish themselves during the two years' course at the college, and who manifest special aptitude, shall have the opportunity afforded them at the Central Institution of prolonging their studies.

The teaching of analysis, in the ordinary sense, is a very unimportant feature in the earlier part of the course. Instead, the student has to solve a series of problems, for instance, to determine the composition of air, of water, and of the gas obtained on heating salt with sulphuric acid, first qualitatively, then quantitatively. He takes note of, and registers, the results obtained, and points out their bearing on the problem he is engaged in solving. He thus learns how to solve practical problems by experiment. Great difficulty has been experienced in getting students to properly observe and interpret the results of their experiments, and it has been only too apparent that their previous education has done little to develop their reasoning faculties.

Students in the chemical department are required to devote a considerable amount of time to mechanical drawing and other mechanical subjects, so that they may become competent to deal with machinery.

[page 408]

Art Department. The Commissioners next visited the art classes under the Institute, which are held in the basement of the middle-class school at Cowper Street, temporarily used for the technical college. Here Mr. A. Brophy, the head master, has special classes for cabinet-makers, designers, and others. He explained his system of teaching to be that each student not only prepared an outline from a copy, but, had subsequently to ink it in, or complete it in colour, so as to form a simple design for inlaid work or some other kind of decoration. He tries, as far as possible, to set before his students copies from the best work of former days, so as to give them a means of acquiring a certain amount of the history of art while they are learning drawing. Thus a number of pupils who were studying drawing with special reference to lithography, were sketching in pen and ink from Dürer woodcuts. In a second room practical designing was being taught, the students being engaged in applications of design to various materials, pottery, colour printing, &c.

The room for drawing from the life was occupied both by male and female students, who were drawing from the draped female model. In another room students were engaged in modelling from the life, also from the draped female figure.

Mr. Brophy stated that he allowed his students to select what class of drawing or modelling they wished to learn, and to go at once, if they could draw at all, to that particular work. He was averse to spending time over carefully finished drawings, and preferred that his students should begin at once with something that interested them, and that they should also, from the first day, practise the use of colour.

Small classes engaged in mechanical drawing, building construction, and practical drawing for carpenters, were also inspected.

Day School. The Commissioners subsequently visited the day department at the Technical College. Professor Perry, the teacher of practical and applied mechanics, showed them the work carried on in his department. In the mechanical laboratory, besides the well-known experiments with the triangle and polygon of forces and other pieces of apparatus described in many books on mechanics, a graduated series of experiments is arranged, by means of which students investigate for themselves the effect of different loads in various machines, of bands on pulleys, and so forth.

Among other experiments of the series are those on the energy of a rotating body; the resistance of wire to extension and torsion, and of beams loaded and supported in various ways, and of the vibration of the pendulum, &c.

The apparatus is nearly all of a novel kind, the student making a complete set of observations of one arranged experiment before he passes on to the next, and the sheets of squared paper, &c., containing the results of his observations, with short descriptions of what he has actually done, are retained by the

[page 409]

student to help in fixing his position in the class list at the end of the session. Professor Perry stated that the investigations of some of the students were of considerable interest and originality.

The Commissioners then saw the workshops. In the carpenters' shop, fitted with benches and lathes, the students were at the time of our visit engaged in making freehand sketches from parts of machinery, which they were subsequently to draw to scale in the drawing room. In the adjoining shop for metal work, fitted up with vices, lathes, and some small machine tools, they were chipping iron. These two workshops are in the charge of a practical mechanic.

Professor Perry showed the Commissioners the engine and boiler fitted up under his superintendence, to drive the dynamo-machine and to furnish the motive power for the building. This has been specially arranged for experimental purposes. The boiler and engine are to be provided with appliances for measuring evaporation, steam temperatures, flue temperatures, steam pressure, condenser temperatures, feed-water temperatures, &c. The shafting is provided with two dynamometer couplings, and the engine is capable of being worked either with or without condensation. A special "evaporative" surface-condensing apparatus in connection with the engine is fitted up on the top of the buildings, by which means a considerable vacuum is obtainable.

The Commissioners then visited the drawing rooms for mechanical drawing, and the large apparatus room or museum on the first floor.

Nearly all the students of the day department follow out the complete course of instruction as laid down in the programme. They come at 9.30 in the morning and remain at the College till 5 in the afternoon, a half-hour being allowed in the middle of the day. All the students undergo a practical course of science instruction in the chemical, physical, and mechanical laboratories. They also learn freehand and machine drawing, and one modern language. Each student spends at least three hours per week in the workshop. The students are admitted only after passing an entrance examination in elementary mathematics. The Clothworkers' Company have given two exhibitions of £30 to the London School Board; one to be awarded annually, and to be available for two years, to a selected pupil from the elementary schools, who, after receiving some preliminary science training, shall pursue his studies at the Finsbury Technical College. By means of these exhibitions and of others tenable at the Central Institution, the Council of the Institute hope to see the way open to boys of exceptional merit from the primary schools, enabling them to deceive the highest technical instruction.

City and Guilds of London Technical Art School, Kennington Park Road, S.E. The Commissioners visited this school and were received by Mr. Owen Roberts, one of the honorary

[page 410]

secretaries of the City and Guilds of London Institute, and by Mr. Sparkes, the superintendent of studies.

This school is carried on in two dwelling-houses which have been thrown into one for the purpose, and large top-lighted class rooms have been built in the rear, for drawing from the life, and for modelling. The department first visited was that for wood engraving. This class, which meets daily, except Saturdays, from 10 to 4, and each evening from 6 to 8, is under the care of Mr. C. Roberts. The students, 11 in number, at the time of our visit, were engaged in practical work, at circular tables specially fitted for the purpose. Four students work at each table, which has an elevated block in the centre for the lamp and glass water lenses. The students are required before entrance to have taken the Second Grade certificate of the Science and Art Department. One evening in each week is set apart for drawing on the wood.

In the class for elementary design, under Miss Walford, the students were all women who were engaged in making designs for tile, wall paper, and other decorative work; the instruction includes, (1) drawing flowers, foliage, and natural forms; and (2) the arrangement of these studies in elementary designs. The advanced class of design is under the tuition of Mr. Hugh Stannus, and at the time of our visit, he was lecturing on design suitable for encaustic and other tiles, to a class of about 15. This course is adapted to students engaged in the practice of ornamental art, and to lithographers, engravers, house decorators, and designers for textile fabrics, pottery, and surface decoration.

In the life room, next visited, a large number of students were making drawings from the nude model; the work, as a rule, was in charcoal, and the aim seemed rather to produce rapid and effective sketches than laboriously finished drawings. The room was almost inconveniently crowded. Some of the students here seemed to have scarcely sufficient power of drawing to be working from the nude. It is a rule in most schools to require that the student, previous to attempting to study from the life, should have some considerable skill in drawing.

In the modelling room some good work was being done, especially from drapery and in bas relief. We were told that a large number of the students were practically engaged in modelling during the day time in the Lambeth potteries. A class for china painting meets here during the daytime twice a week. The attendance during the past year has been as follows:

| Subject | Males | Females | Total |

| Modelling | 48 | 9 | 57 |

| Design, elementary | 4 | 28 | 32 |

| Design, advanced | 9 | 10 | 19 |

| Wood engraving | 4 | 12 | 16 |

| Life classes, drawing and painting | 20 | 9 | 29 |

| 85 | 68 | 153 |

[page 411]

The following have been the occupations of the students recently attending the school:

| Designers | 60 |

| Wood engravers | 30 |

| Stone carvers | 37 |

| Teachers | 19 |

| China painters | 12 |

| Wood carvers | 10 |

| Modellers | 10 |

| Clerks | 10 |

| Art students | 8 |

| Tradesmen | 8 |

| Draughtsmen | 4 |

| Lithographers | 3 |

VIII. THE POLYTECHNIC YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN INSTITUTE, REGENT STREET, LONDON

The Commissioners were received by Mr. Quintin Hogg and Mr. Mitchell, the secretary. Mr. Hooper, a member of the committee, also accompanied them. They were conducted by these gentlemen through the various class-rooms, and Mr. Hogg explained to them briefly the origin of the Institute. The work was started many years ago as a philanthropic effort, and in its first form took the shape of a ragged school, which ultimately developed into the Young Men's Christian Institute, and the building in which the lectures and classes were now being carried on had been purchased by Mr. Hogg for the purpose. The Institute numbers 2,000 members, which is the maximum number admitted, but there are 1,200 applicants awaiting the opportunity of admission. Youths between the age of 16 and 23 are eligible for election, but as the Institute is principally intended for apprentices and young artisans, only 20 per cent of persons not belonging to the artisan class are admitted at any one election. The subscription is 3s 6d per quarter, and a small fee on joining the various classes. In certain cases outsiders are admitted to the classes on payment of double fee, but, practically, three-fourths of those attending the classes are members of the Institute. Special efforts are made by the Committee to provide the members with the opportunity of acquiring a sound theoretical and practical knowledge of their various trades, and care has been taken that the instruction should not be too difficult to be understood by the average mechanic. The following is a list of the systematic trade courses given, with the syllabus of subjects taught, but there are also practical classes for other trades as will be seen from the account. Nearly all these classes are in connection with the City and Guilds of London Institute, their teachers being registered by the Institute and receiving payment on results.

[page 412]

Bricklaying. Practical, Plane, and Solid Geometry, Building Construction, Practical Mensuration, Elementary Sanitary Engineering, Practical Bricklaying.

Metal Plate Work. Freehand and Model Drawing, Practical, Plane, and Solid Geometry, Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Metallurgy, Metal Plate Pattern Cutting, Metal Plate Work.

Electrical Engineering. Geometry, Machine Drawing, Mathematics, Magnetism and Electricity, Applied Mechanics, Acoustics, Light, and Heat; Telegraphy, Electric Lighting, Electric Instrument Making.

Engineering. Geometry, Mathematics, Machine Construction, Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Pattern Making, Steam, Mechanical Engineering.

Plumbing. Geometry, Building Construction, Elementary Chemistry, Sanitary Engineering, Applied Mechanics, Plumbing.

Watch and Clock Making. Practical, Plane, and Solid Geometry, Machine Construction and Drawing, Mathematics, Theoretical Mechanics, Applied Mechanics, Watch and Clock Making.

Carriage Building. Freehand and Model Drawing, Practical, Plane, and Solid Geometry, Mathematics, Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Carriage Building.

The Commissioners first visited the class, numerously attended, for electric lighting. We then inspected the class for photography, in which practical demonstrations were being given. We next proceeded to a large class for tailors' pattern cutting, the work being done in chalk on cloth strained over tables, and the cut patterns being made in brown paper. The teacher, Mr. Humphreys, a self-trained cutter, stated that he had himself invented the methods by which he worked, after carefully studying all the plans adopted in America, Germany, and elsewhere. After having been many years practically engaged in the trade as a foreman cutter, he now entirely devoted himself to literary work, editing a trade paper with fashion plates and patterns, which appears monthly, and teaching classes in the evening. So numerous had been the applications for membership of this class that upwards of 100 students had to be turned away. The next class was one for printing. Here the teacher was explaining the composition of printers' rollers, and giving practical instruction for their preparation. Thence a visit was paid to the class for shorthand writing, and next the workshops were inspected. The class actually at work at the time of the visit was that for plumbers' work, the making of all kinds of lead joints was in progress, and practical plumbing of every kind was going on under the teaching of Mr. Davies, the foreman of a large firm in the trade. Various other classes for practical

[page 413]

work are held on different evenings; thus, for instance, metal turning and wood turning, cabinet-making, carpentry, &c. In the class for tin plate working, which was next visited, Mr. Millis, the teacher, stated to the Commissioners that his instruction was chiefly theoretical, and that he did not consider it necessary to include practical work, as is done in the plumbing class. The drawing and modelling classes, which seemed almost overcrowded, were next visited. The drawing was chiefly outline and shading from casts, but some few of the students were attempting to apply their knowledge to designing, and work of a more advanced character. A theoretical class was also inspected by the Commissioners, in which instruction was being given in watchmaking by Mr. Herrmann.

After a brief inspection of the library and reading rooms, the recreation room, and the arrangements in the basement for lavatories, cloak rooms, &a, the Commissioners adjourned to the large hall and witnessed a display of fencing and gymnastics by some of the more proficient members of the association. Mr. Hogg explained that one of the great attractions of the Institute was the gymnasium, which was largely patronised, and for which members paid an additional fee of sixpence per quarter. He encouraged them to come in their working clothes directly after leaving work, and to spend the whole of the evening at the Institute, refreshments being provided at a moderate cost, and recreation and teaching being jointly cared for. In addition to the teaching on the week-days, the largest adult Bible class in the world (Mr. Hogg believed) is held on the Sunday, when he has an average attendance of 650 young men in one class. In order to give them a sufficient amount of outdoor exercise, he had leased a field of 13 acres at Barnes, for cricket, lawn tennis, football, &c., and he made a practice of inviting all the members of the Institute to stay with him in the country for a week every summer. He could arrange to receive fifty at a time.

The Commissioners understand that Mr. Hogg has expended £80,000,. in the purchase, fitting, and endowment, of the Institute.

IX. ROYAL INDIAN ENGINEERING COLLEGE, COOPER'S HILL

The Commissioners visited the Royal Indian Engineering College, at Cooper's Hill, near Staines, and were received by the President, Gen. Sir Alexander Taylor, K.C.B, and Professors Reilly and Unwin, who explained the objects of the institution and the aims and scope of the teaching. It is now nearly two years since the school was thrown open to students training for the engineering profession generally, having been till then specially maintained by the Indian Government for

[page 414]

the education of engineers for the Public Works Department of that country. It was established in 1871. Formerly students were required to submit to a competitive entrance examination and, at the completion of their training, were entitled to demand employment in India. Now a qualifying examination has taken the place of the competitive one, and while a certain number of Indian appointments are thrown open annually, students attending the college do not bind themselves to enter the Indian Government service. Owing to the doubt which prevailed some years ago respecting the continuance of the school, the numbers fell off considerably, and at the present time there are only 80 students, the college being well adapted for 120. The course extends over three years, and the curriculum consists principally of mathematics, physics, and drawing, besides the subjects of a good general education. The distribution of the work will be seen from the programme in the Appendix.

The Commissioners visited the class rooms, the lecture-room and drawing-room, and the chemical laboratory. Chemistry is at present an optional subject, but after this year it is intended to make it compulsory. The laboratory now contains only 12 working places, but the buildings needed to double it in size are in course of erection. A large new physical laboratory is also about to be built. At present the physical teaching is all given in class, and no experimental work is done. A very handsome drawing school is also being constructed, and the old drawing school will be partly used as a physical lecture room. A visit was paid to the workshops which contain a good collection of lathes and small machine tools driven by a steam engine. Beyond the engineering workshop is a small carpenters' shop, principally used for pattern making. The workshop instruction is optional, and is taken out of school-hours. The workshops are under the charge of Professor Reilly and the work-master, Mr. Hopps, who has given evidence before the Commissioners. A mechanical laboratory is also in course of construction, which it is estimated will cost upwards of £2,000. It will contain a testing machine capable of testing up to 100 tons, a gas engine, some small shaping machines for making specimens for testing, &c. This department is in the charge of Professor Unwin.

A collection of the students' works was shown to the Commissioners, the drawing being extremely creditable, and showing that copying from examples is not encouraged, and that a considerable portion of the students' time is occupied in preparing designs and independent surveys.

The president stated, in answer to questions, that so far as he could judge, the new system of a mere qualifying examination brought them in a class of men, perhaps not quite so well prepared in the first instance, but that in the long run these men compared very favourably with those previously selected by competition.

[page 415]

Each student has a separate bedroom and study. These rooms occupy a special block of buildings.

The number of appointments offered annually by the Indian Government is not sufficient for the whole number of students who are now being educated at the college, and it is supposed that probably some 80 per cent of the students will enter into private employment.

X. ROYAL NAVAL COLLEGE, GREENWICH

We have been furnished with the following facts with respect to the course of instruction pursued in the Royal Naval College by students of marine engineering and naval architecture.

During the first session the study of mathematics, pure and applied, goes on in the mornings. In the afternoons professional subjects, practical physics, and practical chemistry are studied, and courses of lectures on physics and chemistry are given by college professors, between the morning and afternoon studies. The evenings are available for private study and for recreation. Saturday afternoons are also available for the same purposes during the whole of the session, and Wednesday afternoon during about half the session.

The assistant engineers, who remain at the Royal Naval College for two additional years, and the students of naval architecture, have precisely the same instruction in all matters except such as are purely professional. Successful efforts have been made to give each set of students a broad view of the profession studied by the other set of students, by arranging suitable lectures for this purpose.

The morning work consists of the more advanced mathematics, solid geometry, theory of equations, differential equations, hydro-dynamics, rigid dynamics, strength of materials and of structures, &c.

The afternoon work consists of more advanced professional instruction, relating to the design either of a ship or set of engines, all the calculations relating thereto, and the making of complete sets of drawings of all the parts, instead of being confined, as in the first year, to the mere elementary features of the profession.

The study of chemistry and physics takes place during the second and third years in the same manner as in the first, more advanced work being taken in hand as the knowledge of the students increases.

The school has not been so successful in attracting private students, as was anticipated at first, although the total number being educated there now reaches a considerable figure, the naval architects standing at about 30 for foreign students, and 20 for

[page 416]

British students. Many of the British students, however, being engaged in private trade, leave at an early period of their studies, for the purpose of undertaking actual professional work. There have only been about 16 private students of marine engineering in the school, eight foreign and eight British.

The influence of the Royal School of Naval Architecture on the Mercantile Marine has, however, been more felt through Admiralty students leaving the Admiralty service, than by means of private students. The Admiralty students occupy much higher positions in private shipbuilding and engineering firms than private students of the school have been able to secure. The Mercantile Marine has gained in many ways by this introduction of professional men from the Admiralty service. These men have carried with them the high standard of workmanship, traditional in Her Majesty's service, as well as the knowledge necessary to apply principles to new conditions and circumstances.

Lloyd's Register of Shipping has many surveyors who have been students in the school.

The foreign students for the most part, although not exclusively, have been sent by their own Governments, and on the completion of their training have been employed in the constructive offices in their several countries.

Naval officers have a very extended course of instruction in marine engineering, both at sea and at the Royal Naval College. They are instructed when at sea by the chief engineer of the ship, and when in harbour by officers detailed for that purpose. This instruction is given to all officers up to and including the rank of captain, and in the case of the junior officers it is compulsory.

At the Royal Naval College, sub-lieutenants, lieutenants, commanders, and captains attend lectures on the steam engine, and have models of important parts available for illustration. The source of energy by burning coal in air is investigated, the most economical types of engines, causes of breakdown, inefficiency, &c. are explained; the duration of boilers, wear and tear of engines, most economical speed, &c. are all studied in detail.

The course in naval architecture is not so extended at present, and is not of such old standing as the course in marine engineering. Officers are instructed in the leading features of shipbuilding, the names and uses of the several parts, the construction of turrets, methods of ventilation, drawing, watertight sub-divisions, means of maintaining and preserving the hull in a state of efficiency, are dealt with in detail, and some officers have shown considerable aptitude in these studies. Officers are also taught the more elementary scientific proportions of naval architecture, viz., the construction of metacentric diagrams, how to find the centre of gravity of a ship either by calculations

[page 417]

or by experiment, how to calculate the stability of a ship, the arrangements of sail plans, &c.

At the present time there are nine Admiralty students at the Royal Naval College, undergoing a three years' course of instruction in naval architecture; six Admiralty students (assisting and acting assisting engineers, Royal Navy) undergoing a three years' course of instruction in marine engineering; and 39 Admiralty students of the same rank undergoing a nine months' course of instruction in marine engineering.

In addition to the professional students of naval architecture and marine engineering, some of the naval officers receive instruction in naval architecture, and nearly all receive instruction in marine engineering at the Royal Naval College. The particulars are given below:

| Number in the College | Number attending |

| Naval architecture | Marine engineering |

| Captains | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Commanders | 9 | 8 | 5 |

| Lieutenants | 17 | 1 | 10 |

| Navigating lieutenants | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Sub-lieutenants | 66 | 0 | 66 |

These numbers vary from year to year and even from month to month as appointments are made, especially in the case of the senior officers, but the above figures may be looked upon as fair average numbers.

XI. CRYSTAL PALACE SCHOOL OF PRACTICAL ENGINEERING

This school, which we did not visit, is in two divisions, mechanical engineering and civil engineering, under the direction of Mr. J. W. Wilson. It professes to prepare students for taking articles under engineers, or in the case of those who are already articled, it provides systematic practical and scientific work. An aim also of the school is to give such practical instruction as may be valuable to colonists and explorers of new countries.

In the mechanical engineering section, the age on admission must be not less than 16. There is a preliminary entrance examination, and for those unable to comply with its conditions, a preparatory course has been arranged. There are three terms of 15 weeks each. Hours 10 to 1 and 2 to 5 each day. One term is devoted to mechanical drawings a second to pattern making, and a third to fitting and smiths' work. The mechanical course is comprised in one year. The fee for the year is 50

[page 418]

guineas, and for additional terms £17 10s each. Students can be received for a single term on payment of £25.

The civil engineering course also extends over one year, and is designed as a preparation to articles. There is a preliminary examination to test the suitability of the student The first term is devoted to projecting and the practical preparation by actual surveys and levelling of plans in detail, and plans and estimates for Parliament. The second term is devoted to the preparation of detailed section plans, estimates of the above work for the contractor, and the third term is utilized for original designing of girders, bridge work, &c., and the examination of important existing engineering works completed or in progress. The fees for this section are 60 guineas for the course, or 25 guineas for each single term.

At the end of each term there is an examination by engineers of eminence, not connected with the school, and certificates are given for proficiency in lecture subjects and work in the drawing office and shops. A colonial section, for the practical and theoretical instruction of intending colonists, has also been arranged.

XII. OXFORD

The Commissioners met at the University Museum, where they were received by the Curator, Professor H. J. S. Smith, F.R.S., (whose untimely death, shortly afterwards, Science has had to deplore). Professor Moseley, F.R.S., Professor Westwood, and Dr. Acland, F.RS. The history of the foundation of the museum was explained to the Commissioners by Dr. Acland, who pointed out the principles on which the building was constructed, and upon which the various departments of zoology, comparative anatomy, and geology have been arranged, thanks especially to the zeal and ability of the late Professor Rolleston. Students of science, who, however, are not numerous, make much use of the museum for study, and can attend the lectures delivered by the several professors in the rooms attached to the museum, or work in the zoological and physiological laboratories. A new set of laboratories is about to be built for Professor Burdon Sanderson, F.R.S., in proximity to the museum, which is itself so planned as to enable extensions to be made at any time. The extensive entomological collections under the care of Professor Westwood are also housed in the museum, and the herbarium of the late Dr. Daubeny will shortly be included amongst the museum collections. Valuable features of this institution are the Radcliffe and Ashmolean Scientific Libraries, containing more than 50,000 works of reference, and a large and complete lending library of scientific text books and periodicals.

Attached to the museum are the departments of physics and chemistry. The former of these is contained in a separate

[page 419]

building adjoining the museum. The Clarendon Physical Laboratory, under the direction of Professor Clifton, F.RS., the professor of experimental physics, is one of the most complete in this country, and was built at a cost of about £12,000. It contains a series of rooms clustered round a central hall, fitted with glass cases for the storage of apparatus, and a roomy and well arranged lecture theatre, together with workshops and other necessary adjuncts. The several rooms set apart for the students' work are designed with special reference to the branch of physics which the student desires to pursue; thus, certain rooms are occupied by optical apparatus, and are used solely for experiments on light, others are fitted with the necessary arrangements for experiments on heat, and so on. The professor only admits to these practical courses, such graduates or undergraduates as have sufficient mathematical knowledge to benefit from his advanced teaching, and as are capable of handling with the requisite care the expensive and delicate apparatus with which they have to work. The large amount of personal attention which the professor and the university demonstrator are obliged to give to each student working in this laboratory, prevents the classes from being numerous; about twelve students work at optics, and about eight or ten at heat.

The Chemical Laboratories under the direction of Professor Odling, F.R.S., have been enlarged since the museum was built, by 64 places, and now give accommodation for 88 students. The number working at the time of the Commissioners' visit was 51. In addition to the University laboratory, Christchurch has a special chemical laboratory under Mr. Vernon Harcourt, F.R.S., and Balliol a smaller one under Mr. Dixon, whilst inter-collegiate lectures on the various science subjects are given to supplement those of the University professors. Magdalen College has also instituted a physiological and chemical laboratory.

The arrangements and facilities for the study of medicine and the preliminary science subjects are not so advanced at present at Oxford as at Cambridge; the appointment of Dr. Sanderson as the Linacre Professor of Physiology will, it is expected, greatly promote the study of medical science in the University.

The Art Galleries and Schools of Art form an important feature in the educational establishments of Oxford. Professor Ruskin's school is chiefly devoted to landscape and water-colour drawing, and is open to undergraduates and others. A valuable collection of works by Turner and other masters has been presented to the University by Mr. Ruskin, and is much used for copying.

The Government Art School is situated in the basement of the Art Galleries, and is insufficiently accommodated. It is attended by from 50 to 60 students, mostly young, none of whom carry on designing or advanced work.

[page 420]

XIII. CAMBRIDGE

The Commissioners were informed, that previous to the year 1871, no practical teaching of science was carried on in the University, with the exception of chemistry. In that year, the late Professor Maxwell was appointed professor of physics, and designed the Cavendish physical laboratory presented to the University by the Chancellor, the Duke of Devonshire; and Professor Michael Foster was elected as lecturer on physiology in Trinity College. From the above year, up to the present time, science teaching in almost every branch has been instituted, of at once the most advanced and the most practical character.

Maxwell's influence on the examination system of the university, by introducing physical problems in addition to the more purely mathematical subjects formerly in rogue, has been of the highest importance; and that of Professor Foster equally so in another direction, viz., that of encouraging and developing the teaching of the biological sciences, as forming an important part of the scientific training for the profession of medicine. Other eminent Cambridge men, Lord Rayleigh, Professors Stokes, Humphreys, Liveing, Dewar, Vines, Mr. Coutts-Trotter, and the late Professor Balfour among the number, have done much to assist in this matter; and there is no doubt that the authorities of the University generally, are at the present time fully alive to the importance of these practical scientific studies, and are determined to push forward and co-ordinate the still somewhat unsystematic efforts which are being made by the different colleges in this direction. The energy and activity which is thus being displayed at Cambridge is very remarkable.

Of the various scientific institutions and laboratories now existing at Cambridge, the most important are: (1) the Cavendish Physical Laboratory under Professor Lord Rayleigh; (2) the Physiological and Morphological Laboratories, under Professor Foster and Mr. Sedgwick; (3) the Chemical Department under Professors Liveing and Dewar; (4) the Geological Museum under Professor Hughes; (5) the Mineralogical Collection (Professor Lewis); (6) the Mechanical Workshops of Professor James Stuart; (7) the Fitzwilliam Museum; besides (8) the purely professional departments of medicine under Professor Humphreys and others.

(1) The Cavendish Laboratory. This laboratory, which is one of the most complete of its kind, was designed by Professor Clerk Maxwell, and since his death the direction has devolved upon Lord Rayleigh. There are special rooms for optical research, for exact measurements of different kinds, and for special physical research in all its branches. The Professor is assisted by two demonstrators, Messrs. Glazebrook and Shaw, who undertake the elementary instruction of about 45 students, carrying on a specific course of practical work. The demand for this tuition is steadily increasing, the attendance having trebled in the last three years. The fee for working in the laboratory is two guineas per term. There is no endowment in

[page 421]

connection with the department, but a fund amounting to £2,000 has been raised at the instigation of Lord Rayleigh, for the purchase of apparatus. The senior students attend lectures on advanced electricity, given by Lord Rayleigh, who is himself engaged in original physical research, and great stimulus is thus given to the higher work of the students, who assist him.

(2) The Biological Department at Cambridge has grown from very small beginnings in 1871 to a very complete and extensive department at the present time, in buildings specially arranged for the purpose. In the physiological laboratories, 120 students are at present receiving instruction under Professor Foster, assisted by two demonstrators, whilst no less than 80 students are studying morphology in separate laboratories, (designed by the late Professor Balfour), under Mr. Adam Sedgwick. Most of the students are preparing for the medical profession; the total number of the medical students of the three years now at Cambridge amounting to 200. Ladies from Girton and Newnham also attend these laboratories. The cost of these buildings was about £11,000, and a considerable sum for the maintenance of the department will be set apart, under the new University scheme, from the funds of the various colleges. In connection with this department is a valuable museum of comparative anatomy, under Professor Macalister, and a herbarium and botanical laboratory, recently arranged by Professor Vines.

(3) Chemical Department. This department, so far as buildings and accommodation are concerned, is very insufficient. A sum of £30,000 has, however, lately been voted for building a complete set of chemical laboratories and lecture rooms. There are about 185 students of chemistry in the University, of whom about one-third are medical students. The fee for attending the chemical laboratory is two guineas per term, with an additional 17s for apparatus.

Owing to a change which has recently taken place in the statutes, students taking the mathematical degrees are allowed to study natural science in the latter part of their course. Few students have time or inclination for original research.

(4) Geological Museum. This consists of the renowned Woodwardian Museum of Geology and of a large number of collections illustrative of economic geology. The museum has been raised to its present position by the labours of the late Prof. Sedgwick, to whom the existing museum buildings, commenced in 1835, owe their, origin. These valuable collections are employed by Prof. T. McK. Hughes in his lectures. A detailed description of the collection, and of the technical courses which the Professor would wish to see established in Cambridge, will be found in the Appendix, Vol. IV.

(5) The mineralogical collection at Cambridge is one of great value and completeness, having been chiefly formed by the late Prof. W. H. Miller. The department is now under the charge of Prof. Lewis.

[page 422]

(6) The Mechanical Workshops of Professor Stuart. An interesting feature of the present scientific activity at Cambridge is the experiment inaugurated by Prof. Stuart about five years ago, by the establishment of a department for carrying on practical work in machine construction. Prof. Stuart's intention in establishing this department is to enable the sons of manufacturers and others who are sent to the University, to obtain instruction of a kind likely to be of immediate practical value in their subsequent calling. On inspecting the workshops, which are still unfinished and in gradual course of erection, the Commissioners were impressed with the bonâ-fide character of the work. The department contains a fitting shop, smithy, a small erecting shop, and a draughtsman's office, together with a cupola and casting shed. About 42 students were working at the time of the visit. All the men go through a regularly prescribed course of work, special attention being paid to the instruction in mechanical and machine drawing, which is made the foundation of all the teaching in the shops. The system of tuition is arranged on the basis of an actual mercantile establishment. The rate of wages for each student is fixed, the cost of material and the time employed being accurately noted and entered in a ledger, so that the cost of every article produced can be ascertained. An examination of the register of attendance showed that 20 students had in eight weeks attended 725 times and worked 2,121 hours, giving an average of 4½ attendances of 3 hours' duration per student per week. For the purpose of instructing the students, five or six skilled mechanics are employed, who are paid the average wages of their class. Of these, two arc former students of the University, who, having gone through the course, remain as paid workmen. The work in progress during the Commissioners' visit was of a most diverse kind; some of the most advanced students were constructing dynamo-machines, steam engines, telegraphic and electrical apparatus, &c.