[page 124]

CHAPTER VII

THE LION IN THE PATH

I

THE COST OF OUR PROPOSALS

THE exponents of an educational policy may reasonably be asked to offer some indication of the expenditure which it will entail. If it is agreed that a large increase should be made, both in the provision of secondary education and in the facilities for rendering it easily accessible to families of small means, what is the financial cost of such developments likely to be?

The answer to that question must depend upon the degree of rapidity with which the change is introduced. For the reasons stated above, we agree with those educationalists who look forward to the time when the majority of children will spend the years from eleven to sixteen in one kind or another of secondary school. But, even if that policy is adopted as the goal at which to aim, it is obvious that practical considerations, in particular the shortage of accommodation and teachers, will prevent it being carried out except by gradual stages. What we anticipate, in fact, is not any sudden large addition to the expenditure on secondary education, but a steady advance. Fees at grant-aided secondary schools (which, at the moment, with lamentable shortsightedness, are being raised) will be abolished and maintenance allowances increased. Local Education Authorities will meet the present unsatisfied demand for secondary education by adding to their provision of secondary school places, as many have already planned

[page 125]

to do. Increased facilities for obtaining it will in turn stimulate a new demand, as it has been stimulated by the development of secondary education since 1902, and to meet that demand a further increase in the provision will be necessary. The end will be envisaged, it is to be hoped, with comparative clearness. But progress towards it will be experimental. And just as today in some areas ten per cent of the children pass from primary to secondary schools, while in others the proportion is five or less, so in the future one authority will take fifty per cent of them into the secondary schools while another takes only twenty-five. Expenditure will increase, but the increase will necessarily be gradual, and the additional cost at any moment will depend upon the additional provision which has been made.

With this caution, and with the omission of complications arising from future changes in the value of money, it is possible to offer an approximate estimate of the annual financial expenditure which our policy would involve. The additions to expenditure needed to carry it out will fall under three main heads: (i) the abolition of fees at grant-aided secondary schools; (ii) the development of an enlarged system of maintenance allowances; (iii) the provision of additional secondary school places, the main item in which will consist of the salaries of teachers. In the following paragraphs we deal with the annual cost of maintenance under each of these three heads. The estimate is necessarily very rough. But we have endeavoured to err, if anything, on the side of over-statement, and have not taken into account the economies which can be effected by a better co-ordination of primary and secondary education, though we believe them to be considerable.

The cost of abolishing fees can be stated with some accuracy. The income from fees was £1,100,245 in 1912-13, and was estimated by the Departmental Committee on Scholarships and Free Places as approximately £2,000,000 in 1920.(1) This figure, therefore, or slightly more, is the sum which it would cost the nation to free

(1) Op. cit., p. 16.

[page 126]

existing secondary schools without increasing the present school population.

The cost of establishing an adequate system of maintenance allowances cannot be stated with equal precision, since it will vary with changes in the cost of living and the level of earnings. In 1918-19 £253,149 was spent in England and Wales in providing maintenance allowances for 29,796 children in secondary schools, who formed 10.6 per cent of all children in attendance. If, however, the secondary school population increases, a larger proportion of it, and not merely a larger absolute number, will require to be assisted by maintenance allowances. To show the probable cost under this heading, we put that proportion at an arbitrary figure of thirty per cent of the pupils in attendance, which is approximately three times the present proportion. To provide maintenance allowances of the same average value (£8 9s) for thirty per cent of the children would cost the following sums for secondary school populations of different sizes:

England and Wales

(excluding preparatory

departments) | No. of

children | Cost of providing maintenance allowance for 30 per cent of children in attendance |

| Children in secondary schools in England, 1919-20 | 280,336 | £710,649 |

| Children in secondary schools in England on scale of 10 per 1,000 of population | 360,000 | £912,600 |

| Children in secondary schools on scale of 20 per 1,000 of population | 720,000 | £1,810,200 |

| Children in secondary schools on scale of 75 per cent of those leaving elementary schools | 2,250,000 | £5,703,750 |

Assuming therefore that (i) the proportion of children receiving maintenance allowances is trebled; (ii) that the children in secondary schools are increased from 8.7 per 1,000 to twenty per 1,000, the total cost of maintenance allowances would be £1,810,200.

[page 127]

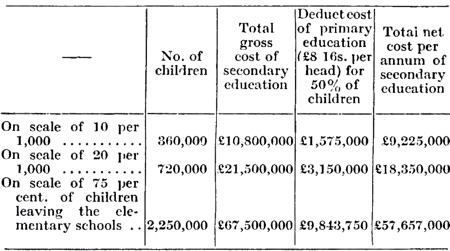

So far, we have not been dealing with very large figures. To free secondary education and to establish maintenance allowances on the largest scale given in the above table would cost a good deal less than half one battleship. The provision of additional school accommodation for a greatly enlarged secondary school population is, of course, a much more serious matter. The annual maintenance cost of a secondary school place is, at present, £28 to £30. The total number of boys and girls between eleven and sixteen is approximately 3,000,000. Of these the children between eleven and fourteen would be attending primary schools if they were not attending secondary schools. In order, therefore, to ascertain the net addition to the national expenditure involved in providing secondary education for them, the cost of educating them in a primary school must, of course, be deducted. To that point we return later. In the following table we give the gross annual expenditure on secondary education on each of three assumptions:

(a) That secondary school places are provided on the scale of ten per 1,000 of the population (instead of, as now, on that of 8.7 per 1,000);

(b) That they are provided on the scale of twenty per 1,000;

(c) That they are provided for seventy-five per cent of the children leaving the primary schools.

GROSS COST OF SECONDARY EDUCATION AT THE RATE OF £30 PER SCHOOL PLACE

| Number of children | Cost per child | Total gross cost per annum |

| On scale of 10 per 1,000 | 360,000 | £30 | £10,800,000 |

| On scale of 20 per 1,000 | 720,000 | £30 | £21,600,000 |

| On scale of 75 per cent of children leaving the elementary schools | 2,250,000 | £30 | £67,500,000 |

[page 128]

In order to arrive at the net cost of secondary school places, it is necessary, as stated above, to deduct from the gross cost the cost of providing primary school places for children between the years eleven and fourteen. The annual maintenance cost of a primary school place is at present £8 15s 9d.(2) According to the last report of the Board (October, 1920) out of 308,372 children in the secondary schools on the Grant List there were 60,505 children between ten and twelve, and 194,665 between twelve and sixteen. It is probable that about half the former and nearly three-quarters of the latter, had they not been attending secondary schools, would have been attending primary schools, approximately 150,000 children in all, or forty-eight per cent of the total secondary school population. If it is assumed that, at any one time fifty per cent of the children receiving secondary education would otherwise have been in primary schools, then the net cost will be shown by the following table:

These figures considerably underestimate the deductions to be made, and therefore overestimate the net cost of providing additional secondary school places, because (i) a growing number of children, if not attending

(2) Seventh Report of Select Committee on National Expenditure (Dec. 1920). The Geddes Report (p. 109) puts it at £12 4s 4d. (1921-2). If its figures are right the deduction to be made is, of course, greater and the net cost of our proposals correspondingly less.

[page 129]

secondary schools, will be, not in primary schools, but in the more expensive central and intermediate schools, (ii) as the secondary school population grows, the percentage of it drawn from primary schools will increase more than in proportion. Obviously, when seventy-five per cent of the children in primary schools pass to secondary schools between the ages of eleven and twelve, the saving on account of primary education will be larger than that suggested above. The nearest estimate we can give would be to say that to provide secondary education on a scale of twenty per thousand of the population would probably cost something over £15,000,000 and under £18,000,000 a year, and that to provide it for seventy-five per cent of the children leaving the primary schools would probably cost something over £50,000,000 and under £55,000,000 a year. For the reasons stated above, any such development can take place only gradually, as teachers are found and accommodation provided. If the former were effected in a period of five years, the addition to the annual expenditure made in each year would be approximately £3,000,000. If the latter were carried out over a period of ten years, the corresponding figure would be £5,000,000.

The total net cost of (a) a minimum programme, (b) a larger programme, based on our policy may, therefore, be set out in the following estimate:

(A) COST OF MINIMUM PROGRAMME AT END OF FIVE YEARS

| Cost per annum

£ |

| Abolition of fees at grant-aided secondary schools | 2,000,000 |

| Provision of school places on scale of 20 per 1,000 of population | 18,850,000 |

| Provision of maintenance allowances for 30 per cent of above number of children in grant-aided secondary schools | 1,810,200 |

| Total | 22,160,200 |

| Deduct present cost of secondary education (1921-22) | 13,468,731(3) |

| Additional cost | 8,691,469 |

(3) This includes some items which are not strictly "secondary" education.

[page 130]

(B) COST OF LARGER PROGRAMME AT END OF TEN YEARS

| Cost per annum

£ |

| Abolition of fees at grant-aided secondary schools | 2,000,000 |

| Provision of school places on scale of 75 per cent of children leaving the elementary schools | 57,657,000 |

| Provision of maintenance allowances for 30 per cent of above number of children in grant-aided secondary schools | 5,703,750 |

| Total | 65,360,750 |

| Deduct present cost of secondary education (1921-22) | 13,468,731(4) |

| Additional cost | 51,891,919 |

The additional cost of our minimum programme, therefore, would be less than that of one battleship. If the nation "ruined itself" by carrying out the larger programme, it would ultimately be spending on all kinds of education (higher and elementary together) about £50,000,000 less than it now spends (1921-22) on the army, navy, and air force.

II

CAN THE NATION "AFFORD" EDUCATION?

The comment of the reader who turns from his Daily Mail to glance for the first time at these figures will be simple: "Very nice, but the nation cannot afford it". At a meeting of the Federation of British Industries a little more than a year ago, held (for the sake of economy) in the Victoria Room of the Hotel Cecil, a certain Mr. Lincoln Chandler - apparently a wagon-builder - is reported, as became one of his profession, to have driven straight to the point, and like Jehu, the son of Nimshi, to have driven furiously. "It was time", he is stated to have said in a series of striking aphorisms quoted by The Times of December, 1920, "they came to plain speaking ... we had embarked on schemes without which we had got on very well. There was the Education Act, the Health Bill, ... and various

(4) See note (3) on previous page.

[page 131]

other schemes. He should like to send a strong message to Mr. Lloyd George that the whole of these schemes should be dropped and dropped at once." Few will question this sage's statement that he had "got on very well" without education. It is even possible that, were education more widely diffused, he and his kind might "get on" somewhat less well in the future. But the enlightenment even of the reluctant is a meritorious act; and, at the risk of boring our readers with commonplaces, we propose to set out shortly, without demanding fees or even engaging the Hotel Cecil, the relevant facts as to educational finance and expenditure, for the benefit of those who do not think that a nation is likely to "get on very well" without education, but who, nevertheless, are apprehensive that educational progress can be secured only at a cost which is beyond its financial resources.

It may be observed, in the first place, that no conclusion can be drawn as to the reasonableness or otherwise of educational expenditure until that expenditure is brought into relation with other items in the budgets both of the State and of private individuals. All magnitudes are relative - a fact which is common (if it is not profane to say so) to the cost both of education and of wagons. Whether a community can or cannot "afford" to arrange that its children shall grow up under conditions calculated to promote their physical and mental development depends not merely - to use the somewhat absurd phraseology favoured by a certain school of politicians - upon the "burden" which such an arrangement will entail, but upon the nature of the other objects to which expenditure is directed. Expenditure is neither more nor less onerous because the money is raised by rates and taxes, and spent by publicly chosen agents consisting of Local Education Authorities, than it is when it is incurred by private individuals upon their own account. Whether it is or is not a "burden" depends upon the relative importance of the objects to which it is assigned. Some things are desirable in themselves, but must be forgone because other things are more urgent. Other things are

[page 132]

futile in themselves, but are acquired because some people have a taste for futilities.

In this matter the only difference between the conduct of the individual citizen and that of a nation is that an individual who indulged his passion for futilities to the point of neglecting his primary social obligations - who turned his house into a fortress armed to the teeth in which he swilled alcohol in the drawing-room and kept his children on short rations in the coal hole - would become amenable to the law, while a whole community by doing the same may earn an agreeable reputation for being practical, high-spirited, and generally an imperial people entitled to sing "Take up the white man's burden, and dump it on the child" to the glory of God and to the exhilaration of all but a few anæmic sentimentalists. But patriotic tunes butter no parsnips. A writer who was at one time thought to know something about business remarked that "what is prudence in the conduct of every private family can hardly be folly in that of a great kingdom". And, if a parent who neglects his children is liable to criminal proceedings, the burden of proving that the same action is highly meritorious when done by several million parents, in the name of economy, appears to rest on those who support that paradox.

The innocent gentlemen like Sir Eric Geddes, Lord Inchcape, and the rest, who suppose that the "taxable capacity" of a nation is a fixed quantity, and that, if more than a certain proportion of the annual product is taken by the State, disaster must follow, irrespective of the objects to which the State applies the money raised, may be invited to console themselves by reading the Report on Credit, Currency, Finance, and Foreign Exchanges prepared by Section F of the British Association. To the question whether the "taxable capacity" of Great Britain has been "reached and passed" the answer given by the majority of economists appears to be that of Sir Josiah Stamp: "There can be no absolute answer, because it depends upon the reasons for, or subjects upon, which the money is to be spent."

[page 133]

It is, in short, quite idle to discuss expenditure on education except in connection with expenditure on other subjects. Whether a nation can "afford" it or not, depends upon whether it is or is not more important than other purposes on which it is spending money. When, therefore, the Select Committee on National Expenditure deplored(5) the "alarming increase" in the cost of education, it was not merely mistaken (though, of course, it was mistaken) as to the financial facts, it showed a complete ignorance as to elementary financial principles. It relapsed, in fact, from the mendacious into the meaningless. To do it justice, it appears to have been equally at home in both.

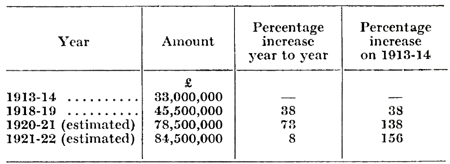

The facts as to educational expenditure appear to be widely misunderstood, and the misunderstanding is not altogether the fault of the public. It is not merely that, in the nature of things, no complete estimate of the total educational expenditure of the country can be given, since there is no way of ascertaining the expenditure of private individuals. There is the further, and more surprising fact, that there appears to be no one official document in which all the facts as to public expenditure on education are brought together. The figures in Tables I. -III. below are reprinted, by kind permission of its authors, from the excellent Bulletin(6) on Education issued by Cambridge House. For an account of the sources used and for further information on several points of importance, the reader is referred to the Bulletin in question. For the use made of the figures, and for the conclusions drawn from them, we alone, of course, are responsible.

(5) Seventh Report from the Select Committee on National Expenditure (December 21, 1920), p. xiv.

(6) Cambridge House Bulletins, Education I, to be obtained from Cambridge House, 131 Camberwell Road, London, S.E.

[page 134]

TABLE I(7)

TOTAL PUBLIC EXPENDITURE (CENTRAL AND LOCAL) ON EDUCATION IN ENGLAND AND WALES

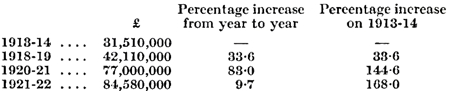

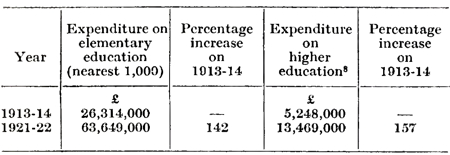

This increase is divided between elementary and higher education as follows:

(7) The corresponding figures in the First Interim Report of the Committee on National Expenditure (p. 107) - the so-called "Geddes Report" - are as follows:

The discrepancy between the figures given above and those of the Geddes Committee is small. According to the former, the increase in educational expenditure since 1913-14 is 156 per cent; according to the latter, 168 per cent. But it is sufficient to give point to what is said above on the urgent need that a complete and reliable report on the cost of education should be published annually by the Board, instead of this vital question being left to private investigators or to a committee of business men who are without practical knowledge of the subject matter. The explanation of the discrepancy is to be found in the fact that Table I above includes certain small receipts by Local Education Authorities from fees, the sale of books, &c., which the Geddes Report excludes, and in certain minor ambiguities in the educational statistics contained in the statistical abstract. It may be further observed that the figures published by the Geddes Committee disagree with those published in the Seventh Report of the Committee on National Expenditure (December, 1920).

[page 135]

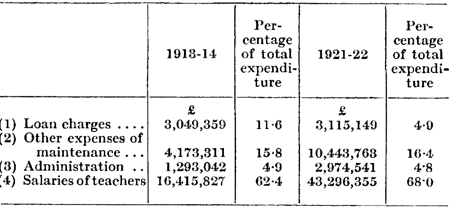

TABLE II

It is important to know the main items on which the increase has been incurred. Light is thrown upon that point by the following figures, which, however, relate only to elementary (not to higher) education.

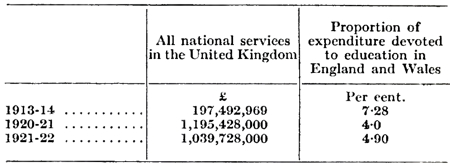

TABLE III

Finally, it is perhaps worth setting out the proportion of the national expenditure devoted to education at different dates (similar figures for local expenditure are not available):

(8) The corresponding figures in the Geddes Report are - 1913-14: £4,402,000; 1921-22: £13,500,000. Percentage increase 1913-14/1921-22: 206.7.

[page 136]

TABLE IV

From the above tables the following conclusions appear to emerge:

(i) The money expenditure on public education (elementary and higher) is 156 per cent (or, on Geddes' figures, 168 per cent.) higher in 1921-22 than it was in 1913-14.

(ii) The main cause of the increase of £51,000,000 (or, on Geddes' figures, £53,070,000) between those dates is the increase in the salaries of teachers, those of elementary teachers having increased by £26,880,528; those of secondary and other teachers by an uncertain, but substantial, figure. Minor causes of the increase are that repairs and building, postponed during the war, have been executed since the Armistice at high prices, and that the salaries of officials have risen. It must also be remembered - a fact sometimes apparently forgotten - that the child population has been growing since 1913-14!

(iii) The proportion of the national expenditure devoted to education fell from 7.28 per cent in 1913-14 to 4.9 per cent in 1921-22.

These figures relate only to the money cost of education. Before, therefore, any precise significance can be attached to them, it is necessary to set them in relation to (1) expenditure on other objects, public and private; (2) changes in the general price level, and, in particular, in the cost of living. This we attempt to do in the following table:

[page 137]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 138]

The first fact which these figures show is that the talk of the "alarming increase" in the cost of education is misleading. When account is taken of the devaluation of money, the increase in educational expenditure since 1913-14, though real, is hardly "alarming", especially when compared with the increased expenditure upon other objects. The degree of reliance to be based upon the widely advertised seventh report of the Select Committee on National Expenditure may be judged from the fact that this elementary point, which lies at the very threshold of the subject, was either unknown to, or deliberately suppressed by, that body of financial experts! The truth is that, measured in goods and services, which, of course, alone matter, the nation was actually applying a smaller sum to education in December, 1920 - the time when the committee reported - than it did seven years ago. It is actually the case, though the reader will hardly believe it, that the same suppressio veri [misrepresentation] was repeated, without a word of caution or explanation, by the so-called Geddes Committee. Between 1913 and 1921 the income liable to income tax increased from £907,151,813 to £2,500,000,000. Would Sir Eric Geddes and Lord Inchcape hold that there had been an "enormous increase" in the real incomes of the wealthier classes since 1913? If not, why do they suggest that there has been an "enormous increase" in the real cost of education?

It will be observed, in the second place, that the nation spent in 1920-21 more than five times as much on drink as it spent on education - the drink bill, indeed, is enormous partly because the education bill is too small - and that the expenditure on armaments three years after the termination of hostilities is considerably more than twice that on education. The disproportion is so immense that it would still remain large even if the proposals made in this pamphlet were carried out. In the event of effect being given to the "minimum programme" set out above, and of no other changes in expenditure taking place, the nation would still be spending almost

[page 139]

twice as much on the armed forces as on education. If the larger programme were realised, its expenditure on the former would still exceed its expenditure on the latter by over £50,000,000 a year, or considerably more than the total sum spent on the army in 1913-14!

In face of facts of this order it is quite idle for Select Committees, "business men", or any one else to deplore "the alarming increase in the cost of education", because, in reality, when account is taken of the devaluation of money, no very great increase has taken place, and, if it had, it would not be alarming, since (as the figures show) the nation can meet it by cutting down some of the extravagances both of its government and of its individual members. Like the revolutionary Tribunal which told Lavoisier that "the Republic has no need of chemists", Lord Inchcape may see in education nothing but economically unproductive expenditure. It is time, however, that the business classes and their servants in the Cabinet and in Parliament stopped mistaking their personal prejudices for economic facts. By far the largest item in the increase in the money expenditure upon education consists of the advance in teachers' salaries. If a man's heart leaps up at the thought of employing soldiers, sailors, and publicans, and sinks to his boots at the thought of employing teachers, he is entitled to his opinion. One cannot argue with the choice of a soul, and if he likes that kind of thing then that is the kind of thing he likes. But his private sentiments, even when he sits on a Select Committee or in the Cabinet, have no more relevance to economic realities than have those of any other old gentleman who thinks that the world is coming to an end because he has to pay more for his cigars. A certain section - happily for the nation, not the most representative section - of the English governing classes have always thought that the most desirable way of saving money was to reduce the height, weight, vitality, and intelligence of the children of people poorer than themselves, on the ground, presumably, that such canaille [common people] can hardly be expected to take the same

[page 140]

interest in life as their own. But not every one is an economist who chooses to make speeches or issue reports about "economy", and when these respectable cannibals propose to "economise" on education, they provoke the retort that it would be considerably more economical for the nation to economise on them.

We do not, therefore, ask whether there is not a certain absurdity in applying the rigours of the economic calculus to boys and girls of fourteen, whether the policy of "making the children pay for the war" is quite the most appropriate tribute to the fathers who fell in it, whether, if the ship is really sinking, "women and children last" is the motto by which the British Empire desires to be remembered. The paladins who are leading the attack on the schools appeal to economic facts, and to economic facts they shall go. The total sum spent on higher education in 1913-14 was slightly less than the sum paid to rather less than 4,000 owners of mineral royalties, which (in other connections) we are informed is a bagatelle, and in 1921-2 is almost exactly equal to the average annual profits of the coal industry for the five years 1909-13. The salaries of 16,000 teachers for continuation schools under the Act of 1918, at an average of £300 a year, would have been £4,800,000, or slightly less than the profits (before deductions for income tax and excess profits duty) made in a single year - 1919 - by a single firm - Coats' Combine - more than £2,000,000 less than the profits - £6,925,005 - made in 1921 by the Imperial Tobacco Company, and approximately £2,000,000 less than the expenditure of the Government on its farcical military preparations for cowing the miners last summer, when the cutting down of education, because "the nation could not afford it", had already begun. If the Education Act of 1918 had been brought into operation with the greatest possible speed, the total additional expenditure on education by 1924 would probably have been something approaching £10,000,000, or rather more than the cost of one battleship. If the larger of the two programmes outlined above were to be developed steadily for the next decade,

[page 141]

the additional annual expenditure at the end of it would be something less than half what has been spent since the Armistice in financing and arming military adventurers against Russia, not to mention Mesopotamia and Ireland.

III

THE CONCLUSION OF THE MATTER

So far, then, as the facts of the financial situation are concerned, the attack on educational expenditure breaks down in the very court to which it appeals. The nation is not "crushed by educational expenditure". It has not "reached the limit of what it can afford". It is not true that "no money is available for educational improvements". On the contrary, money which ought to be spent on education is being thrown away with both hands on extravagances, both private and public. The critics of education may be admirable, if somewhat austere, moralists. But as financiers they do not know the elements of their subject. If the community is induced, with the object of effecting what are called (though not by economists) "economies", to make another raid on the health and intelligence of its children, it must not lay the flattering unction to its soul that it does so under the stress of financial necessity. Whatever the causes of the financial burden which it bears, they are certainly not to be found in excessive expenditure on education.

In reality, of course, neither is it a mere objection to increased expenditure on education which is the impelling cause behind the attack upon it, nor is it a mere exposure of the hollowness of that objection which will enable the attack to be defeated. The interests which are resisting educational progress today, on the ground that "we cannot afford it after the war", are precisely the same as those which resisted it before the war began. Their motives are various: partly a fear that more education will mean less cheap juvenile labour, partly the idea that, if they are better educated, working-class children will forget their place and be less fitted, in the elegant

[page 142]

words of the Federation of British Industries, for "the employments which they eventually enter", partly a dislike of any movement which is likely to diminish economic and social inequalities, partly mere ignorance, which is not altogether their own fault, of what education is and means, and a doubt whether, after all, it is not a useless luxury invented by faddists for the advantage of teachers and administrators.

With those who are attacking education because it threatens their personal profit or social position it is not necessary to argue. The larger number who are doubtful whether it is "worth it" may be invited to consider both the practice of other countries and the experience of their own. It is improbable, to put it mildly, that the whole civilised world is out of step except themselves. Thanks to the war and the peace, comparisons based on money expenditure are almost meaningless. But if the ingenuous journalists who denounce education as a "fad" will look at our Allies, they will find that the expenditure of France on education has increased since 1913 to a considerably greater extent than has that of this country. "In America", stated the United States Commissioner of Education in 1920, "it is now generally held that expenditure for education must be doubled at least before the opportunities for education can in any adequate measure meet the needs of the people and the demands of public opinion."(16) The appropriations in 1920 were approximately 1,000,000,000 dollars or, roughly £200,000,000 to £250,000,000. If these were doubled, the expenditure would be between £400,000,000 and £500,000,000; and it must be remembered that even in 1913 the public secondary schools in America were almost universally free, that the education given in the State Universities was often virtually free, and that the proportion of children passing from the primary schools to both was far higher than in England. What precisely is happening in Germany cannot be stated in figures. But it is

(16) The Teachers' World, October 20, 1921.

[page 143]

known that since the war there has been in many parts of the country an educational revival, and that, amid economic difficulties far exceeding those of this country, a determined effort is being made to rebuild by means of education the resources of the nation.(17)

Such facts should remind us that talk about the cost of education, which ignores the effect of it on character and intelligence and physical well-being, on the output of industry and the amenity of social life, is as rational as a discussion of one side of a balance sheet without reference to the ether. When it is stated that "taxation is crushing industry" what actually is supposed to occur? The phrase appears to be used in several different senses. But the principal suggestions which it is intended to convey seem to be two. The first is that taxation diminishes the incentive to effort, by diminishing the reward which effort receives. The second is that the State collects in taxes and spends on current account wealth which, if left in the hands of the taxpayer, would have been saved and used as capital, with the result either that the material equipment of industry is not improved as quickly as is desirable, or that, in extreme cases, it actually runs down. "The capital", to quote Mr. McKenna,(18) "which the keen, active, enterprising man could use to the utmost advantage in developing trade, is taken from him, and spent unproductively on one of the manifold activities of the State."

Now, it is true, of course, that both these results are possibilities, and that both have actually occurred in the past, though probably not (except in so far as the war is concerned) in the recent past. But it is evident also that the appearance of these disastrous consequences depends on the presence of a factor which most of the popular complaints of "taxation crushing industry" overlook or do not mention. It is conditional on the money raised

(17) See The Observer, January 29, 1922: "Far from wishing to economise on education, all political parties are encouraging it to the utmost."

(18) The Times, January 28, 1922.

[page 144]

by taxation being spent, as Mr. McKenna says, "unproductively" - on its being used by the State in such a way as not to increase the resources of the nation or to add to its capacity for economic effort. Whether taxation is "crushing" or not cannot, therefore, be decided merely by pointing to the sums which are raised. It is equally essential to consider the way in which, when raised, they are spent. No serious financier has ever supposed that the effect on industry of spending £100,000,000 on armaments is the same as that of spending £100,000,000 in paying off part of the national debt. No one ought to suppose that it is the same as that of spending £100,000,000 on education or public health. In the first case the capacity to produce goods and services (other than armaments) is diminished: in the second case that capacity is increased. The truth is that ill-health and ignorance are an economic burden which no society can afford to carry once it has learned how to lighten it. Every one of the 1,000,000 children in the primary schools suffering from physical ailments whose health is impaired through failure to provide suitable and early treatment for it, or whose mental development is arrested because it is prematurely snatched from school, or whose morale is lowered during the critical years of adolescence by alternate overwork and unemployment, represents not an "economy" but the most unintelligent, as well as the most cruel, of extravagances. It is possible for the personnel as well as the material equipment of industry to be under-capitalised, and a nation which has the courage to invest generously in its children "saves", in the strictest economic sense, more "capital" than the most parsimonious community which ever lived with its eyes on the Stock Exchange.

"Never will I believe", said Macaulay in 1846, "that what makes a population stronger and healthier and wiser and better can ultimately make it poorer. ... If ever we are forced to yield the foremost place among commercial nations, we shall yield it to some nation pre-eminently vigorous in body and mind." His words were

[page 145]

spoken in defence of factory legislation, which was opposed by industrial interests on somewhat the same grounds as education is opposed today. But they are equally applicable to the questions of educational policy which are the subject of this memorandum. A nation can no more impoverish itself by cultivating the intelligence of its children than by developing any other of the resources with which nature has endowed it. From a purely economic standpoint the most important part of the capital of a country consists of human beings. Wealth applied to improving their physical and intellectual attainments is the most remunerative of all investments, since it adds to that particular type of productive power on which the ability to use all other natural advantages, and to overcome natural disadvantages, ultimately depends. In the partnership "between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born", which forms the life of society, almost the most vital link is the provision which each generation makes for posterity by means of education.

For Great Britain, even on purely economic grounds, the issue is peculiarly crucial. Fifty years ago, in warning his fellow countrymen of the future exhaustion of the coal resources on which for a century and a half the wealth of this country has rested, Jevons pleaded for "a general system of education which may effect for the future generation what is hopeless for this present generation. ... At present it may almost be said to be profitable to breed little slaves."(19) Since Jevons wrote, there have been three great Education Acts and a host of minor measures. But the nation is still far from having made provision for the full development of the most important of its national resources - the health and the intelligence of its children. Yet the effect of investing money in them will endure when other sources of wealth have begun to fail.

(19) Jevons, "The Coal Question", preface to second edition. See also Money, "The Nation's Wealth."

[page 146]

It is one of the tragedies of English social history that in the period of swiftly increasing returns between 1850 and 1890, when wealth was growing by leaps and bounds and taxation was hardly felt, the opportunity of creating a really effective educational system was missed, because riches came so easily that education seemed unimportant. What then could have been done without any considerable economic effort requires today a larger measure of foresight and self-discipline. But the need for it is even more urgent. The course of wisdom for Great Britain, which owes its modem economic development largely to a single, and a wasting, asset, and which, even before the war, had lost some of the adventitious facilities for industrial leadership which it possessed almost up to the end of the nineteenth century, would be to use a large part of the wealth of a coal age which will one day draw to a close to establish the most comprehensive system of education that educational science can suggest. On this matter, at any rate, the economists speak with no uncertain voice. Professor Bowley, who will not be suspected of under-estimating the importance of economic considerations, pleads for "better education" as one way of increasing the output of wealth, by securing "a much fuller use of the latent abilities of the race than hitherto has been possible."(20) Professor Marshall, in an oft quoted passage, after stating that "perhaps £100,000,000 annually are spent even by the working class, and £400,000,000 by the rest of the population of England in ways that do little or nothing towards making life nobler or truly happier", urges that "it is the young whose faculties are of the highest importance both to the moralist and the economist. The most imperative duty of this generation is to provide for the young the best education for the work they have to do as producers and as men and women, together with long continued freedom from mechanical toil and abundant leisure for school."(21)

(20) Bowley, "The Division of the Product of Industry", p. 57.

(21) "Principles", pp. 786-7.

[page 147]

Let the reader reflect on the present life of hundreds of thousands of boys and girls, on the prevalence of physical ailments among them, on their premature overwork, on their hurried and truncated schooling, on the waste of capacity caused by the failure to make smooth the way to higher education - let him consider that it is on these boys and girls, on their energy and foresight, their individual ability and their capacity for social co-operation, that the prosperity of the nation in fifteen years will depend - and he will not think it extravagant to suggest that they should be educated up to sixteen under the most favourable conditions that the progress of educational science can offer. The generation which is now mature has not left a pleasant world to its successors. It can at least put into their hands the tools with which to rebuild the ruins that surround them.

[page 149]

Appendices

[page 150]

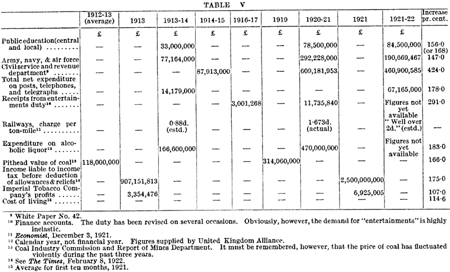

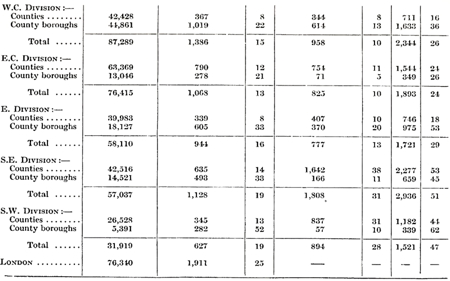

APPENDIX - TABLE I

A very rough indication of the inequality of educational opportunity as between different areas is given by this table, which should be read in connection with Table III. It is calculated from Tables B and D, Appendix I, of the Report of the Departmental Committee on Scholarships and Free Places, and shows the proportion which applicants for admission to secondary schools, who were refused admission at the beginning of 1919-20, bear to the number of children between ten and eleven in the elementary schools. It should be noted that the variations in the percentage of Column (6) to Column (1) in different areas represent differences of demand as well as differences of supply. On the other hand, experience suggests that the supply of secondary education affects the demand for it.

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 151]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 152]

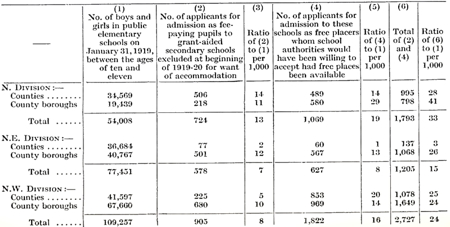

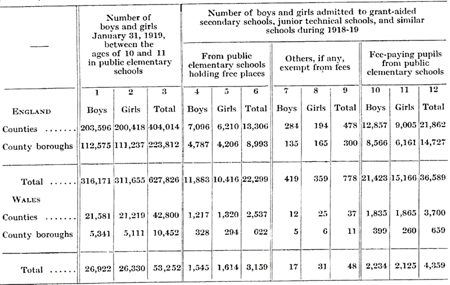

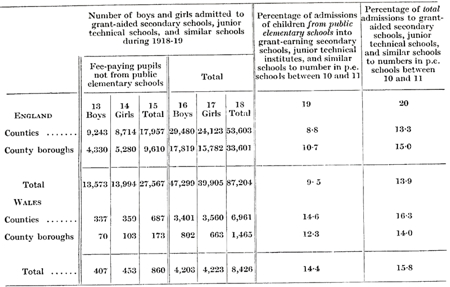

APPENDIX - TABLE II

(From the Report of the Departmental Committee on Scholarships and Free Places (Cmd. 369), App. I Table B)

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 153]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 154]

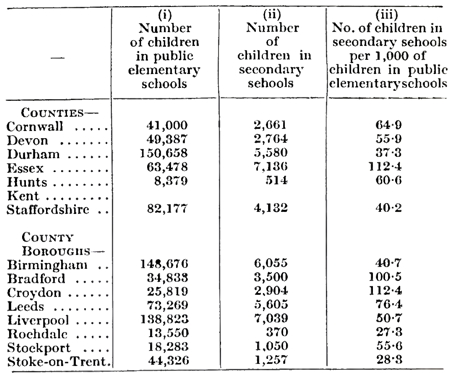

APPENDIX - TABLE III

In the following table an attempt is made to show the varying relation between the elementary and secondary school populations (a) in certain counties and county boroughs of England, (b) in the United States. The source used for (a) is the schemes of the local authorities concerned, for (b) Sandiford, "Comparative Education", page 61.

The figures relating to England are not satisfactory, and we present them only with great hesitation. They are not always strictly comparable; some authorities, for example, give figures of the children on the registers of public elementary schools, others of average attendance; some include in the secondary school population schools recognised, but not aided, by the local authority, others include only schools aided or maintained; some appear to have excluded from their totals children resident outside the area in which they attend school, others do not. For these and other reasons they must be regarded as, at best, an approximation. They may be of some small service pending the publication of more exact comparative statistics.

(a)

Figures indicating the relation between the elementary and secondary school population in certain counties and county boroughs of England and Wales

[page 155]

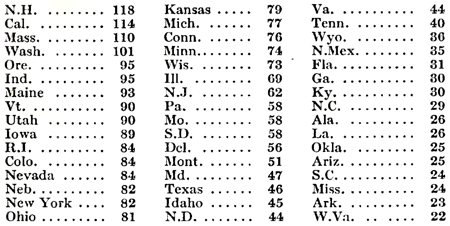

(b)

Pupils in high schools in various States in 1910 for each 1,000 in elementary schools