Education in the UK

Preliminary pages

Introduction, Contents, Preface

Chapter 1 Up to 1500

Beginnings

Chapter 2 1500-1600

Renaissance and Reformation

Chapter 3 1600-1660

Revolution

Chapter 4 1660-1750

Restoration

Chapter 5 1750-1860

Towards mass education

Chapter 6 1860-1900

A state system of education

Chapter 7 1900-1923

Secondary education for some

Chapter 8 1923-1939

From Hadow to Spens

Chapter 9 1939-1945

Educational reconstruction

Chapter 10 1945-1951

Labour and the tripartite system

Chapter 11 1951-1964

The wind of change

Chapter 12 1964-1970

The golden age?

Chapter 13 1970-1974

Applying the brakes

Chapter 14 1974-1979

Progressivism under attack

Chapter 15 1979-1990

Thatcher and the New Right

Chapter 16 1990-1997

John Major: more of the same

Chapter 17 1997-2007

Tony Blair and New Labour

Chapter 18 2007-2010

Brown and Balls: mixed messages

Chapter 19 2010-2015

Gove v The Blob

Chapter 20 2015-2018

Postscript

Timeline

Glossary

Bibliography

Organisation of this chapter

Background

The education of the working class

1861 Newcastle Report

1862 Revised Code

1870 Elementary Education Act

Background

Summary

The church problem

The school boards

The elementary schools

Conclusions

Three more Acts (1873-79)

1880 Elementary Education Act

1882 Mundella Code

1891 Elementary Education Act

Two further Acts (1897, 1900)

The teachers

Infant schools

Literacy

Attendance

Higher elementary education

Higher Grade Schools

1886-8 Cross Commission

Scholarships

The education of the upper class

1864 Clarendon Report

Management of the schools

The curriculum

Upper-class preserves

1868 Public Schools Act

The education of the middle classes

1868 Taunton Report

Taunton's findings

Endowments

Management and administration

The three-grade scheme

The curriculum

The education of girls

Examinations

The reform of endowments

1868 Endowed Schools Act

1869 Endowed Schools Act

The Endowed Schools Commission

1874 Endowed Schools Act

1895 Bryce Report

Scotland

Elementary education

Secondary education

The education of girls

Science and technology

1871-75 Devonshire Reports

1882 Aberdare Report

1882/84 Samuelson Reports

1889-1892 Further Acts

The education of girls

Child welfare and special educational needs

Child welfare

Special educational needs

Provision for

the deaf and blind

the physically and mentally handicapped

defective and epileptic children

Higher education

New colleges

Oxford and Cambridge

1862 Oxford University Act

1871 Universities Tests Act

Polytechnics

And finally ...

The government of education

1888 Local Government Act

1899 Board of Education Act

Mundella's legacy

Education and society

Social conditions

Socialism and education

Initiatives

A common education for all

Education as a science

References

| |

Education in the UK: a history

Derek Gillard

first published June 1998

this version published May 2018

© copyright Derek Gillard 2018

Education in the UK: a history is my copyright. You are welcome to download it and/or print it for your own personal use, or for use in a school or other educational establishment, provided my name as the author is attached. But you may not publish it, upload it onto any other website, or sell it, without my permission.

A printer-friendly version of this chapter can be found here.

Citations

You are welcome to cite this work. If you do so, please acknowledge it thus:

Gillard D (2018) Education in the UK: a history www.education-uk.org/history

References

In references in the text, the number after the colon is always the page number (even where a document has numbered paragraphs or sections).

Documents

Where a document is shown as a link, the full text is available online.

© Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.

Chapter 6 : 1860-1900

A state system of education

Background

Queen Victoria, who ruled from 1837 until her death in 1901, presided over a nation enjoying high levels of peace and prosperity. England had undergone huge political and social changes, coupled with the rapid development of industry and the expansion of a world-wide empire. The Great Exhibition of 1851 epitomised the country's new-found self-confidence. In the second half of the century the population of England and Wales almost doubled - from 16.8 million in 1851 to 30.5 million in 1901.

The two great political figures of the period were Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) and William Gladstone (1809-1898). Disraeli, a Tory favoured by the Queen, served two terms as Prime Minister, from February to December in 1868 and then from 1874 to 1880. Gladstone, a Liberal (the Whig party merged with other groups and adopted the name Liberal around 1850), was Prime Minister four times (1868-74, 1880-85, February to July 1886, and 1892-94). He had an uneasy relationship with Victoria.

England had no state education: schools belonged mostly to the churches and had been allowed to develop in line with the country's class structure. The United States, by contrast, had begun establishing a public school system based on a common education for all its citizens by the 1830s.

Many groups had campaigned for more and better education, especially for the children of the working class, but they had not been supported by the middle and upper classes, who were 'fearful of state control of education' (Chitty 1992:6) nor, at least before 1870, by the Liberal Party, which traditionally believed in freedom and diversity, and in 'the supreme virtue of limited government' (Chitty 1992:5).

By the 1860s, however, it was becoming clear that any complacency about Britain's position in the world, or the state of its education system compared with that of continental countries, was misplaced:

The Paris Exhibition of 1867 revealed a high level of industrial technique in other countries, particularly Germany, and it had been made clear that this rested not only on a high standard of technical education but also on universal elementary schooling (Simon 1974:359).

Sadly, when the British government finally began to acknowledge its responsibility for educating all its people, it not only allowed the class divisions to continue, but exacerbated them. Three national education commissions were established, the reports of each - and the Acts which followed them - relating to provision for a particular social class. In chronological order these were:

- The Royal Commission on the State of Popular Education in England, appointed in 1858. The 1861 Newcastle Report led to the 1870 Elementary Education Act which made provision for schools for the masses;

- The Royal Commission on the Public Schools, appointed in 1861. The 1864 Clarendon Report and the 1868 Public Schools Act dealt with the 'great' public (ie private) schools; and

- The Schools Inquiry Commission, appointed in 1864. The 1868 Taunton Report and the Endowed Schools Act of 1869 dealt with schools for the middle classes.

Nonetheless, it is important not to underestimate the extent of the changes that took place between 1870 and 1902, as Stephens points out: 'elementary education became both free and compulsory, state elementary and secondary schools were established and central government control over education increased greatly' (Stephens 1998:77).

The education of the working class

Before 1870, elementary education was provided largely by the Church of England's National Society and the nonconformist British and Foreign School Society. The government had, however, made grants to these two bodies from 1833, and arrangements governing the distribution of the grants had been set out in an annual Code of Regulations, first published in a Committee of Council Minute of 24 September 1839.

1861 Newcastle Report

(Note: references in this section are to Volume I, which contains the main report, except where indicated otherwise.)

By the late 1850s it was clear that the churches were unable to provide sufficient school places for all children, so the Royal Commission on the State of Popular Education in England, under the chairmanship of the Duke of Newcastle, was appointed in 1858

To inquire into the state of public education in England and to consider and report what measures, if any, are required for the extension of sound and cheap elementary instruction to all classes of the people (Newcastle 1861:1).

The Commission published its six-volume report in 1861. It noted that

The whole population of England and Wales, as estimated by the Registrar-General in the summer of 1858, amounted to 19,523,103. The number of children whose names ought, at the same date, to have been on the school books, in order that all might receive some education, was 2,655,767. The number we found to be actually on the books was 2,535,462, thus leaving 120,305 children without any school instruction whatever. The proportion, therefore, of scholars in week-day schools of all kinds to the entire population was 1 in 7.7 or 12.99 per cent. Of these 321,768 are estimated to have been above the condition of such as are commonly comprehended in the expression 'poorer classes', and hence are beyond the range of our present inquiry. Deducting these from the whole number of children on the books of some school, we find that 2,213,694 children belonging to the poorer classes were, when our statistics were collected and compiled, receiving elementary instruction in day schools. Looking, therefore, at mere numbers as indicating the state of popular education in England and Wales, the proportion of children receiving instruction to the whole population is, in our opinion, nearly as high as can be reasonably expected. In Prussia, where it is compulsory, 1 in 6.27; in England and Wales it is, as we have seen, 1 in 7.7; in Holland it is 1 in 8.11; in France it is 1 in 9.0 (Newcastle 1861:293).

But it went on to warn:

We are bound to observe, however, that a very delusive estimate of the state of education must result from confining attention to the mere amount of numbers under day school instruction. We have seen that less than three years ago there were in elementary day schools 2,213,694 children of the poorer classes. But of this number, 573,536 were attending private schools, which, as our evidence uniformly shows, are, for the most part, inferior as schools for the poor, and ill-calculated to give to the children an education which shall be serviceable to them in after-life. Of the 1,549,312 children whose names are on the books of public elementary day schools belonging to the religious denominations, only 19.3 per cent were in their 12th year or upwards, and only that proportion, therefore, can be regarded as educated up to the standard suited to their stations. As many as 786,202 attend for less than 100 days in the year and can therefore hardly receive a serviceable amount of education, while our evidence goes to prove that a large proportion, even of those whose attendance is more regular, fail in obtaining it on account of inefficient teaching. Much, therefore, still remains to be done to bring up the state of elementary education in England and Wales to the degree of usefulness which we all regard as attainable and desirable (Newcastle 1861:294-5).

The Report was also critical of the quality of education provided:

we have seen overwhelming evidence from Her Majesty's Inspectors, to the effect that not more than one-fourth of the children receive a good education. So great a failure in the teaching demanded the closest investigation; and as the result of it we have been obliged to come to the conclusion that the instruction given is commonly both too ambitious and too superficial in its character, that (except in the very best schools) it has been too exclusively adapted to the elder scholars to the neglect of the younger ones, and that it often omits to secure a thorough grounding in the simplest but most essential parts of instruction. We have shown that the present system has never completely met this serious difficulty in elementary teaching; that inspection looks chiefly to the upper classes and to the general condition of the school, and cannot profess to examine carefully individual scholars; and that a main object of the schools is defeated in respect of every child who, having attended for a considerable time, leaves without the power of reading, writing, and cyphering in an intelligent manner (Newcastle 1861:295-6).

The Commissioners rejected any suggestion that attendance at school should be made compulsory or that it should be extended - the labour market required the employment of children, and

if the wages of the child's labour are necessary, either to keep the parents from the poor rates, or to relieve the pressure of severe and bitter poverty, it is far better that it should go to work at the earliest age at which it can bear the physical exertion than that it should remain at school (Newcastle 1861:188).

There was considerable disagreement between the Commissioners over the funding of education, with some (the 'voluntaryists' - see the previous chapter) believing that 'the interference of Government with education is objectionable on political and religious grounds' (Newcastle 1861:297). However, they noted that 'all the principal nations of Europe, and the United States of America, as well as British North America, have felt it necessary to provide for the education of the people by public taxation' (Newcastle 1861:297), and they proceeded to:

propose means by which, in the first place, the present system may be made applicable to the poorer no less than the richer districts throughout the whole country; secondly, by which the present expenditure may be controlled and regulated; thirdly, by which the complication of business in the office may be checked; fourthly, by which greater local activity and interest in education may be encouraged; fifthly, by which the general attainment of a greater degree of elementary knowledge may be secured than is acquired at present (Newcastle 1861:327-8).

The Commissioners commented that infant schools for children up to the age of seven were 'of great utility': they were places of security as well as of education, since they were the only means of keeping children of poor families off the streets in town, or out of the roads and fields in the country. They distinguished two types of infant school: the public infant schools, which often formed a department of the ordinary day school; and the private or 'dame' schools, which were very common in both town and country but were frequently little more than nurseries in which 'the nurse collected the children of many families into her own house instead of attending upon the children of some one family' (Newcastle 1861:28).

1862 Revised Code

The Newcastle Commission recommended that a grant should be paid in respect of every child who, having attended an elementary school, passed an examination in reading, writing and arithmetic (Newcastle 1861:545).

To achieve this, the Code of Regulations for 1862 (commonly known as the Revised Code) introduced the 'payment-by-results' system. It stipulated that every scholar for whom grants were claimed must be examined according to one of six 'standards' in the 'three Rs' - reading, writing and 'rithmetic. To achieve this, the Code of Regulations for 1862 (commonly known as the Revised Code) introduced the 'payment-by-results' system. It stipulated that every scholar for whom grants were claimed must be examined according to one of six 'standards' in the 'three Rs' - reading, writing and 'rithmetic.

The Revised Code is sometimes referred to as 'Lowe's Code', after its creator, Robert Lowe (1811-1892) (pictured), who had been appointed Vice-President of the Committee of Council on Education in 1859. Because of Lowe's opposition to religious influence in education, grants were dependent only on regular school attendance and proficiency in the three Rs: 'they were not awarded for religious instruction' (Stephens 1998:18).

Lowe told the House of Commons that he could not promise

that this system will be an economical one, and I cannot promise that it will be an efficient one, but I can promise that ... if it is not cheap it shall be efficient; if it is not efficient it shall be cheap (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:290).

Expenditure on education had risen from £125,000 in 1848 to over £800,000 in 1861. The effect of the Revised Code was to reduce this to around £600,000 in the mid 1860s, though it began to rise again later in the decade, and more so after the 1870 Elementary Education Act, partly because of greater school attendance (Lawson and Silver 1973:290).

As a result of the Code, elementary schools were organised on the basis of annual promotion. Classes in the senior department were named Standards I to VI, roughly corresponding to ages 7 to 12.

Lawson and Silver note that 'The machinery introduced by the code was narrower than that proposed by the Newcastle Commission' (Lawson and Silver 1973:290):

Each child over the age of six was to earn the school a grant of 4s. on the basis of attendance, and 8s. 'subject to examination'. Of the latter 2s. 8d. was forfeited for failure to satisfy the inspector in reading, 2s. 8d. in writing and 2s. 8d. in arithmetic. Children were to be presented in six 'standards', and not a second time in the same or a lower standard. Children under six were exempted from examination only under last-minute pressure (and these earned a grant of 6s. 6d. subject to a general report by the inspector as to the suitability of their education) (Lawson and Silver 1973:290).

The payment-by-results system was also applied to evening classes, so pupils attending cookery classes, for example, had to be tested in the standard elementary subjects. As a result, attendance at evening classes diminished.

Right from the start there was much opposition to the Code.

Teachers objected partly to the method of testing, but mainly to the principle of payment by results because it linked money for schools with the criterion of a minimum standard. Thus the higher primary work which was beginning to appear before 1861 in the best elementary schools was seriously discouraged. The curriculum became largely restricted to the three Rs, and the only form of practical instruction that survived was needlework. Furthermore, the standards themselves were defective because they were based not on an experimental enquiry into what children of a given age actually knew, but on an a priori notion of what they ought to know. They largely ignored the wide range of individual capacity, and the detailed formulations for the several ages were not always precise or appropriate. 'No system could have been better designed to limit and stultify the educational process' (Simon 1965:116):

Teachers saw it as their duty, indeed a necessity, to get as many children through the examination as possible, and the most effective way of doing this, especially with very large classes, was by rote learning and drilling. Children learned their reading books off by heart (Simon 1965:116).

TH Huxley (1825-1895) noted that 'the Revised Code did not compel any schoolmaster to leave off teaching anything; but, by the very simple process of refusing to pay for many kinds of teaching, it has practically put an end to them', while Matthew Arnold bemoaned the fact that inspectors could not 'go beyond the three matters, reading, writing, and arithmetic' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:290).

Even inspectors who supported the principle of the Revised Code

reported its deadening and disheartening effects. The need to drill the children to meet the inspection requirements was reflected in the schools' activities throughout the year. Frequent testing became common. Some of the improvements of the 1850s in curriculum and method in many schools were cut short (Lawson and Silver 1973:291)

Writing in 1911, former inspector Edmond Holmes described the process as 'that deadly system' which seemed to have been devised 'for the express purpose of arresting growth and strangling life' (Holmes 1911:vii).

Child after child stands up, reads for a minute or so, and then sits down, remaining idle and inert (except when an occasional question is addressed to him) for the rest of the time occupied by the so-called lesson. In this, as in most oral lessons, the elementary school child passes much of his time in a state which is neither activity nor rest, - a state of enforced inertness combined with unnatural and unceasing strain (Holmes 1911:125)

The result of this process, he argued, was that

The child who leaves school at the age of fourteen will have attended some 2,000 or 3,000 reading lessons in the course of his school life. From these, in far too many cases, he will have carried nothing away but the ability to stumble with tolerable correctness through printed matter of moderate difficulty. He will not have carried away from them either the power or the desire to read (Holmes 1911:128).

Edward Thring (1821-1887), head of Uppingham School, said later that the effect of the Code had been to treat children's minds like 'specimens on a board with a pin stuck through them like beetles' and he urged teachers to 'strive for liberty to teach, have mercy on the slow, the ignorant, the weak' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:292).

In 1858 Sir Charles Adderley (1814-1905), Vice-President of the Committee of Council on Education, had declared that

any attempt to keep the children of the labouring classes under intellectual culture after the very earliest stage at which they could earn their living, would be as arbitrary and improper as it would be to keep the boys at Eton and Harrow at spade labour (quoted in Simon 1965:120).

While this sort of language was seen by many as inappropriate, 'in practice it could hardly be said that the intellect of the workers' children was effectively cultivated during the brief period they remained in elementary schooling' (Simon 1965:120).

The training colleges were also badly affected by the Revised Code: 'it reduced their grant, their numbers (by decreasing the number of Queen's scholars) and their standards' (Lawson and Silver 1973:292). The number of pupil teachers fell from 14,000 in 1861 to 9,000 in 1866, with schools for the poorest children worst hit.

The payment-by-results culture became ingrained in teachers. It was 'a view of the nature of elementary education from which it took the system generations to recover' (Lawson and Silver 1973:292).

However, the Code's strict conditions were gradually relaxed over the following thirty years: more freedom of classification was allowed, the tests were made more elastic, and examinations were taken by sample only.

By the 1890s there were signs of more effective teaching in the higher standards, largely because many teachers were doing their best, 'under extraordinarily difficult circumstances, to introduce some humanity into the schools, to develop the intellectual capacities and widen the general outlook of their pupils' (Simon 1965:119). The standards system began to fall into disuse and was finally abandoned by the Board of Education around the turn of the century, except for a few special purposes such as examining candidates for labour certificates.

As for Lowe himself, he went on to oppose the extension of the franchise, warning that giving workers the vote would 'subvert the existing order of things' and 'transfer power from the hands of property and intelligence, and ... place it in the hands of men whose whole life is necessarily occupied in the daily struggle for existence'. Following the passing of the Reform Act in 1867, he said he now believed it would be 'absolutely necessary to compel our future masters to learn their letters'. He saw education as divided into two distinct branches - 'the education of the poor or primary education, and the education of the middle or upper classes' (quoted in Simon 1974:355). Both needed reform, he said.

1870 Elementary Education Act

Background to the Act

Since the late eighteenth century and the industrial revolution, demands for mass education had been closely associated with campaigns for workers' rights. These demands had been opposed by the voluntaryists led by Edward Baines (1774-1848), but the 1867 Reform Act convinced many - including Baines himself - of the need to educate the newly enfranchised working men. Since the late eighteenth century and the industrial revolution, demands for mass education had been closely associated with campaigns for workers' rights. These demands had been opposed by the voluntaryists led by Edward Baines (1774-1848), but the 1867 Reform Act convinced many - including Baines himself - of the need to educate the newly enfranchised working men.

In March 1869, following the publication of the Report of the Royal Commission on Trade Unions, MP Tom Hughes, with the support of Liberal MP AJ (Anthony) Mundella (1825-1897) (pictured), introduced a bill for the legalisation of the unions. In a Commons debate, MP for Carlisle Edmund Potter, a vehement opponent of the Trades Union Bill, declared:

Many of the trade unionists are uneducated men. The government must therefore not only legislate next year for trade unions; they must bring in a strong education measure; for it is only by a very strong compulsory education bill - I do not care how strong - that we can hope to make much impression on trade unions (quoted in Armytage 1951:72).

Compulsory education was supported by the unions, notably the mineworkers, and by the newly-formed Trades Union Congress, held at Birmingham in August 1869, which unanimously passed a motion declaring that 'this Congress believes that nothing short of a system of national, unsectarian, and compulsory education will satisfy the requirements of the people of the United Kingdom' (quoted in Simon 1974:362).

It was also supported by groups such as the Christian Socialists, and - for the first time - by some industrialists, partly because factories had new and more complex machinery and therefore no longer needed child labour; in fact, children of ten or twelve 'could now be more trouble than they were worth' (Simon 1974:359).

To draw all these forces together, the National Education League was formed, with George Dixon (1820-1898) as chairman, Liberal MP Jesse Collings (1831-1920) as secretary, and Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) as Vice-President. Its inaugural meeting was held in Birmingham in October 1869. The League aimed at making education

secular (to remove it out of the hands of priests of all denominations), compulsory (to overcome the tendency of squires and small manufacturers to keep children away from school), and free (in order to overcome the artisan's objection to losing the labour of his children) (Armytage 1951:72).

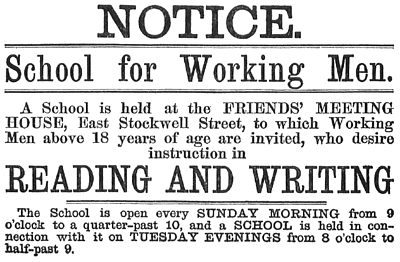

The League campaigned for the provision of schools throughout the country, to be run by local authorities who would be empowered to levy a rate. Within nine months it had set up Working Men's Auxiliary Committees, mainly in the midlands and the north, enrolled forty MPs, and amassed considerable funds.

When the League sent a deputation to Westminster in 1870, the prominent trade unionist Robert Applegarth (1834-1924) described 'the great determination there is on the part of the working classes to speak for themselves on these great questions' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:352).

And a conference of miners' delegates declared

not that they wanted more wages, not that they wanted shorter working hours, or any special remedy of that sort; but the first and most important thing they have declared is, that they must have compulsory education for their children (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:352).

The Liberal MP William Forster (1818-1886) (pictured), who had been appointed Vice-President of the Privy Council in 1868, shared many of the views of the National Education League, but believed that making education compulsory would be impractical, at least in the short term, and that making it secular would risk a major confrontation with the churches which he - and the Prime Minister, Gladstone - were anxious to avoid. The Liberal MP William Forster (1818-1886) (pictured), who had been appointed Vice-President of the Privy Council in 1868, shared many of the views of the National Education League, but believed that making education compulsory would be impractical, at least in the short term, and that making it secular would risk a major confrontation with the churches which he - and the Prime Minister, Gladstone - were anxious to avoid.

Mundella himself 'kept the education question well to the forefront of parliamentary attention' (Armytage 1951:73). In his maiden speech he said he knew of one village where the parishioners had appointed a roadmender as their school teacher, only to find that he was not only incompetent, but irremovable. In a speech on the Poor Laws Mundella called for the 'better employment of those charitable funds, which are sufficient in amount to provide for the education of the whole country' (quoted in Armytage 1951:73), and he urged Forster (unsuccessfully) to empower the Endowed Schools Commission to nationalise non-educational endowments. His grim portrayal of educational provision was resented by the Conservatives but supported by MPs in industrial areas. As a result, Forster ordered statistics to be compiled for four large towns - Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham.

Back in Sheffield, Mundella told his constituents:

The more you educate, the more good you have done, and the more poverty and wretchedness you put an end to. As much money has been wasted over the war in Abyssinia as would educate every child in the British Dominions at the moment. I am not a convert to the League. I have been a convert to national compulsory education for years when many of my friends thought I was going mad (quoted in Armytage 1951:73-4).

Meanwhile, Forster prepared a memorandum on an education bill for submission to the Cabinet on 21 October 1869. He outlined two options: that districts should rate themselves; or that voluntary effort should be encouraged to supply such deficiencies as there were. On 24 November he was informed that the cabinet had agreed to the preparation of an education bill on the basis of his memorandum.

Forster and Mundella met several times to discuss proposals for the bill, and Mundella conducted his own investigation into the standard of education provided for industrial workers. He found, for example, that of the 154 children employed in Stockport, 'thirty could not write at all, eighteen wrote wretchedly, and ten only moderately' (Armytage 1951:76).

The churches, objecting to the secularist policies of the National Education League, established the rival National Educational Union, which aimed at 'judiciously supplementing the present denominational system' (Armytage 1951:76) and urged that rate aid should be available only for the education of pauper children.

Edward Baines, who displayed 'consistent hostility to any form of state aid to education' (Armytage 1951:76), put forward a bill which proposed to extend the work of the Anglican National Society and the nonconformist British and Foreign School Society by providing 'such additions as may be needed to complete the education of the working classes' (Armytage 1951:77). He enlisted the support of the Earl of Shaftesbury, who, twenty years earlier, had written in his diary:

I dread, sadly dread, the schemes for national education. A scheme for local rates to maintain the education of the people is a death warrant to the teaching of the evangelical religion. It had better be called 'a water rate to extinguish religious fire among young people' (quoted in Armytage 1951:77).

Introducing the government bill on 17 February 1870, Forster acknowledged the help he had received from both Dixon and Mundella. He told the Commons:

what is the principle relied upon by the hon. Member for Birmingham (Mr. Dixon) and the hon. Member for Sheffield (Mr. Mundella), to whom so much credit is due for stimulating educational zeal in the country? It is the education of the people's children by the people's officers, chosen in their local assemblies, controlled by the people's representatives in Parliament. That is the principle on which our Bill is based; it is the ultimate force which rests behind every clause (Hansard House of Commons 17 February 1870 Vol 199 Col 465).

Forster's bill allowed six months for the British and National societies to bid for funds for new schools. After that, school boards would be established to provide schools where they were still needed. These 'board schools' would be maintained out of local rates.

Mundella was critical of the bill for failing to make school attendance compulsory. But he was equally critical of the National Education League's demand for secularism, believing that this would result in the bill being lost. During the second reading of the bill he spoke against George Dixon's secularising amendment, calling it 'a miserable religious squabble' (quoted in Armytage 1951:78). His speech was well received and praised by both Disraeli and Gladstone. Forster also 'steadily set his face against secularism' (Armytage 1951:77) and Dixon withdrew his amendment.

When clause 65 of the bill was debated, Mundella moved the case for compulsory school attendance. He told the Commons:

Under the protection of the police I have recently explored some of the crowded parts of London, and the sights which I have seen were of the most horrible character. I saw courts in which children, poor, miserable, squalid and neglected, were as thick as flies in a sugar cask. In one court the children were so thick that I could hardly help putting foot upon them. Their parents were in the gin shop. Within a few yards of this House there are thousands of children who never come in contact with human love, who never hear a virtuous sentiment, who never have any teaching but that of the streets, whose parents are to be found in the gin-palaces and the public-houses; and yet the state neglects these children because, forsooth, it respects the 'liberty of the parents'. Yes, this is tolerated in the name of civil liberty, of paternal liberty and of paternal rights; and the results are such, in twenty districts of London, that no language can describe them, and that none can see them, except under the protection of the police. I tested dozens of these children, and I did not find one in twenty who could say the Lord's prayer, or make out words of one syllable (quoted in Armytage 1951:79).

Forster, clearly moved, said he agreed with Mundella, but that it would be impossible to enforce school attendance until there were enough schools. In the event, the 1870 Act gave school boards the power to enforce compulsion, but it did not compel them to do so.

Mundella then pressed - successfully - for the adoption of ballots for school-board elections so that nonconformists would get a share of the representation. 'It was the bitterest fight in which I was ever engaged', he wrote (quoted in Armytage 1951:79).

Educational historians have traditionally viewed the advent of compulsory state-funded and state-controlled public schooling as 'a development benevolently contrived and part and parcel of the democratization of society, bringing benefits to all'. More recently, however, historians of different outlooks 'have cast doubt both on the motives of those who supported and engineered change and on whether it was necessary or desirable' (Stephens 1998:81).

Historians of the left, Stephens suggests, have 'tended to regard compulsory education in state-controlled schools as an intensification of the use of schooling as a tool of social control'; while those on the right take the view that 'private schooling could well have coped with working-class needs' and that the deficiencies of such schools 'were exaggerated by politicians and by an Education Department whose officials and inspectors had a vested interest in public schooling and lobbied for its extension' (Stephens 1998:81).

Summary of the Act

While, with some justification, 1870 can be described as the year in which the government finally accepted responsibility for the education of the nation's children, the 1870 Act was only the start of a process which would take more than twenty years to complete.

The Elementary Education Act of 1870 was the most workable piece of compromise legislation in English nineteenth-century history. It did not introduce free or compulsory education, but it made both possible. It did not supersede the voluntary schools, it supplemented them. It brought the state into action in education as never before. It created, in the school boards, the most democratic organs of local administration of the century, but left the boards' opponents in positions of strength (Lawson and Silver 1973:314).

The 1870 Elementary Education Act (9 August) made provision for the elementary education of all children aged 5-13, and established school boards to oversee and complete the network of schools and to bring them all under some form of supervision. Such a strategy, it said, would have to be affordable and acceptable to the many sectional religious interests.

The Act required the provision of sufficient school places for all children, but it did not make education free (except in proven cases of poverty), and while it empowered school boards to frame by-laws making attendance at school compulsory for children between the ages of five and thirteen, it did not require them to do so. By the end of 1871, 117 school boards had instituted by-laws requiring some degree of compulsory attendance, but these by-laws were often subject to numerous exemptions.

Part I of the Act (sections 4-95) dealt with the local provision of schools. It began by requiring that every school district should have sufficient public schools:

There shall be provided for every school district a sufficient amount of accommodation in public elementary schools (as herein-after defined) available for all the children resident in such district for whose elementary education efficient and suitable provision is not otherwise made, and where there is an insufficient amount of such accommodation, in this Act referred to as 'public school accommodation,' the deficiency shall be supplied in manner provided by this Act (Section 5).

School boards were to be formed for areas where there was currently insufficient provision (6).

Regulations for the conduct of public elementary schools were set out in section 7. These included the right of parents to withdraw their children from religious instruction.

Sections 8-13 set out the Education Department's powers to determine whether additional school places were required, to require the formation of school boards and to requisition them to provide the extra schools.

Sections 14-36 listed the powers and duties of school boards for the management and maintenance of their schools. These included:

- the requirement that 'No religious catechism or religious formulary which is distinctive of any particular denomination shall be taught in the school' (14);

- the power of school boards to appoint managers (15);

- the duty of school boards to 'keep efficient' every school provided by them, and to provide 'additional school accommodation as is, in their opinion, necessary' (18);

- the powers of school boards to purchase land compulsorily (20);

- paying for new schools out of the local school fund or Treasury loans to be repaid within five years (21); and

- legal matters relating to the transfer of a school to a school board (23) and the re-transfer of a school by a school board to the managers (24).

School boards were empowered to support the education of the poor:

The school board may, if they think fit, from time to time, for a renewable period not exceeding six months, pay the whole or any part of the school fees payable at any public elementary school by any child resident in their district whose parent is in their opinion unable from poverty to pay the same; but no such payment shall be made or refused on condition of the child attending any public elementary school other than such as may be selected by the parent; and such payment shall not be deemed to be parochial relief given to such parent. (25)

and

If a school board satisfy the Education Department that, on the ground of the poverty of the inhabitants of any place in their district, it is expedient for the interests of education to provide a school at which no fees shall be required from the scholars, the board may, subject to such rules and conditions as the Education Department may prescribe, provide such school, and may admit scholars to such school without requiring any fee. (26)

School boards were also empowered to contribute to or establish industrial schools (27-8).

Matters relating to the operation of school boards were set out in sections 29-36. These included:

- their constitutions (30);

- elections (31);

- disqualification from membership (34);

- the appointment of officers (35); and

- the appointment of an officer to enforce attendance at school (36).

Corresponding arrangements for the school board for London were set out in sections 37-39.

Sections 40-73 dealt with a range of administrative and financial matters including:

- the Education Department's powers to form united school districts, other than in London (40-8);

- the Department's powers to require a school district to contribute to the costs of another (49-52);

- the management of school funds (53-56);

- borrowing by school boards (57-58);

- accounting and auditing of school funds (59-62);

- provisions relating to school boards in default (63-66);

- the duty of local authorities to make returns to the Education Department (67-72); and

- the power of the Education Department to hold public inquiries (73).

In relation to school attendance (74), the Act empowered school boards to make by-laws 'Requiring the parents of children of such age, not less than five years nor more than thirteen years, as may be fixed by the byelaws, to cause such children (unless there is some reasonable excuse) to attend school'. Boards were also empowered to determine the time during which children were to attend school (with exceptions for religious observance); and to pay all or part of the school fees of any child whose parents were in poverty.

The remainder of Part I of the Act (75-95) covered various technical and administrative matters.

Part II of the Act, dealing with the parliamentary grant, stated that:

After the thirty-first day of March one thousand eight hundred and seventy-one no parliamentary grant shall be made to any elementary school which is not a public elementary school within the meaning of this Act.

No parliamentary grant shall be made in aid of building, enlarging, improving, or fitting up any elementary school, except in pursuance of a memorial duly signed, and containing the information required by the Education Department for enabling them to decide on the application, and sent to the Education Department on or before the thirty-first day of December one thousand eight hundred and seventy. (96)

Conditions for such grants - totalling not more than 'seven shillings and sixpence per child' (37½p) were laid out in sections 97-99, and included the stipulation that 'Such grant shall not be made in respect of any instruction in religious subjects'.

Finally, section 100 required the Education Department to provide an annual report to Parliament.

There were five Schedules to the Act, dealing with various administrative matters.

The church problem

The dual system - of voluntary and board schools - created by the Act was 'an untidy compromise', but it did represent 'another step towards secularization and state control' (Stephens 1998:79).

The 'Cowper-Temple clause' (pronounced 'Cooper-Temple') in section 14 of the Act ('No religious catechism or religious formulary which is distinctive of any particular denomination shall be taught in the school') was named after its proposer, Liberal MP William Cowper-Temple (1811-1888). It banned denominational teaching in the new board schools.

But in other respects, the 1870 Act failed to resolve the problem of the involvement of the churches in state educational provision. It could have begun to separate church and state, as was happening in other countries. 'That this did not happen was based on a combination of economic realism, institutional convenience and a political predisposition to enjoy religious company in spite of its irks' (Gates 2005:18).

The churches had not been able to make universal provision, so the state would now fund schools managed by locally elected and interdenominationally representative school boards. Church schools would continue to receive a maintenance grant of up to fifty per cent, but once the system was in place they would get no money for new buildings.

Some assumed that the 1870 Act would result in a gradual decline in the number of church schools and their replacement by board schools. The churches, however, were determined to strengthen and consolidate their position, so they took full advantage of the generous offer of government funds for new buildings.

In the six months allowed, the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church 'moved with great alacrity to plan as many as they could' (Gates 2005:19). Two thousand requests for building grants were made by the National Society, five hundred by the Catholic and Free Churches. In just fifteen years, the number of Church of England schools rose from 6,382 to 11,864, and Catholic schools from 350 to 892. In the same period, the number of children attending church schools doubled to two million.

The cost of sustaining this expanded provision was huge. 'Knowingly or not the churches had overreached themselves' (Gates 2005:19), and 'the initial impetus given to voluntary-school building by the passing of the Act could not be maintained' (Lawson and Silver 1973:320). During the 1890s the number of voluntary schools fell by over 350 (there were 14,500 in 1900), while the number of board schools rose by almost a thousand.

Some church leaders complained about what they saw as the unfair financial advantages enjoyed by the board schools. In 1882 Roman Catholic Cardinal Manning declared that the administration of the Act was 'open to the censure of inequality and injustice' (quoted in Armytage 1951:217), while the Anglican Canon Gregory argued that the 1870 Act had

endowed with the school rate those who had done nothing and it has excluded those who have hitherto educated the people of England from participation in the school rate, to which they are also nevertheless compelled to pay (quoted in Armytage 1951:217).

The Church of England - to its shame - even sought to undermine the new system by attempting to prevent the election of school boards. 'The arguments were, as in the past, less concerned with education than with religion, politics, power and finance' (Lawson and Silver 1973:321). (For more on this issue see The School Boards below).

Mundella understood the motive behind these attacks and wrote to a friend:

I keep screwing up [ie improving] the quality of education and insist on the quantity being ample, and all this makes increased and increasing demands upon the voluntary system, and brings the poorer school gradually in the hands of the board. That is the real reason for Manning's outcry (quoted in Armytage 1951:217).

In June 1883 the National Society sent a memorandum to Gladstone asking for assistance. Mundella wrote to Lord Carlingford, Lord President of the Council, to warn him of the danger of acceding to their demands:

I have felt now for more than a year past that this demand would be made. Cardinal Manning and Canon Gregory have struck up an arrangement (in which they have endeavoured, but unsuccessfully, to include the Wesleyans) to agitate for increased grants to voluntary schools. A series of articles have appeared in the Nineteenth Century from the pens of these two ecclesiastics making out the best case they can for their claims. These have been very effectively replied to by the Rev. R. W. Dale of Birmingham, who not only showed with great force and clearness the injustice of the demand, but also the consequences likely to follow upon it, viz. a renewed agitation for the abolition of all grants to schools set up by various religious bodies.

I am sincerely anxious for educational progress and I believe we shall best secure this by the maintenance of the compromise of 1870. I am confident, however, that any attempt to depart from this compromise, any attempt to share the rates or differentiate the grants made to voluntary or board schools, would plunge us into a bitter agitation, viz. the complete severance of education from the control of the various religious bodies and the establishment of a system of national education under the management of the state. Already I find it sufficiently difficult to meet the attacks upon the weaker and less defensible portions of our present system, especially upon the training colleges. ... Still, if those who have benefited most by the act of 1870 are so unwise as to attack it, or if the Government were so ill advised as to show a doubtful mind in dealing with the present demand, I am satisfied that serious agitation would follow, and that education would in all probability suffer until a final settlement was arrived at (quoted in Armytage 1951:219-20).

In 1884 the newly formed interdenominational Voluntary Schools Association began lobbying for greater public funding for church schools. Four years later the Cross Commission (details below) reviewed the working of the 1870 Act and recommended public funding for the secular curriculum in church schools, a proposal which was eventually included in the 1902 Education Act (details in the next chapter).

The school boards

As a result of the Act, 2500 new school boards were created in England and Wales between 1870 and 1896. They varied greatly in size: London was, inevitably, the largest, while some rural boards controlled just one school.

They were directly elected and independent of existing forms of local government. All ratepayers - including women - could vote and stand for election. As single-purpose authorities they were able, in large towns, to attract candidates of high quality. In 1902, EA Knox, chair of the Birmingham School Board, argued that the success of the boards had been mainly due to

the calibre of those whom they attracted as members, especially in their earlier years. School Boards enlisted the activity and zeal of many eminent men and women of strong philanthropic instincts who, for various reasons, had not hitherto enjoyed any similar opportunity of public service. ... A seat on the School Board was a highly-coveted honour (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:318).

The boards were 'a representative social phenomenon' (Lawson and Silver 1973:323). They became 'a focus of new social pressures and of a new interest in democratic processes', though their lessons in democracy were 'not always salutary' (Lawson and Silver 1973:319):

Elections were often sectarian battles between Church of England and nonconformity, between candidates pledged to educational development and those pledged to save the ratepayers' money, or between political parties. ... Some of the smaller boards in rural areas were controlled by people who had opposed their creation, and were pledged to restrict their activities (Lawson and Silver 1973:319).

Problems arose in many towns including, for example, Chester, where local opposition delayed the setting up of a board; in Liverpool, where 'school board politics became part of the struggle between Orangemen and Roman Catholics'; in Birmingham, where 'religious and political controversy often absorbed prodigious amounts of school boards' time and money'; and in Manchester, Salford, Sheffield and Leeds, where clerical and other opponents gained control of the boards. 'In such cases parsimony often ruled' (Stephens 1998:92).

In her 1938 book A Century of City Government: Manchester 1838-1938, Shena Simon noted that the city's School Board

had a majority of Churchmen and Roman Catholics for the whole of its existence, and these members were elected primarily to see that the new Board schools which they had to manage did as little damage as possible to their own schools, in which many of them were naturally more interested (Simon 1938:240 quoted in Simon 1965:158-9).

Throughout the 1880s Anglicans and Roman Catholics, who had consistently opposed popular control of education, attacked the School Board system with increasing confidence while at the same time demanding increased support for voluntary schools from public funds.

Rural areas - especially those in which the Church of England was strong - fared just as badly, with boards consisting 'largely of local farmers and Anglican laymen and clergy, antipathetic to the education of those they regarded as future agricultural labourers' (Stephens 1998:93).

But the picture was not entirely a negative one:

the working class had at last some opportunity of exercising control over the schooling of their children. With the first school board elections working-class candidates were in the field and a few were successful. Thomas Henry Huxley, whose scientific lectures to workers had made him a popular figure since 1855, was elected a member of the first London School Board and managed to ensure that elementary science was included in the curriculum of the capital's new board schools (Simon 1974:366).

Furthermore, most of the boards were remarkably successful: they 'pursued active and progressive policies and numbered influential personalities among their elected members' (Stephens 1998:93). Many began to appoint their own inspectors who, unlike HMIs [Her Majesty's Inspectors], were recruited mainly from experienced elementary-school head teachers (Lawson and Silver 1973:322).

The London board had 55 members and controlled almost 400 schools. It was not only the largest but also the most influential, the architecture and layout of its schools being widely copied. Its leading figures, such as Huxley, 'commanded national respect' (Lawson and Silver 1973:322). It took the board just twelve years to catch up with the 250,000 or so children in voluntary schools, and by the time it was abolished it had more than 500,000 school places (Lawson and Silver 1973:320-1).

The vast scope and achievements of the London School Board made it a national institution. It erected buildings which set standards for others to emulate; it established a system of school attendance officers, known somewhat euphemistically as 'visitors', who soon provided a wealth of detailed and reliable information about the lives of the urban poor; and it appointed its own medical officer to report on air space and the ventilation of classrooms and to examine children with special needs. ... Between 1871 and 1903, the number of pupils in board schools in London rose from 1117 to 549,677, while those in voluntary schools dropped from 221,401 to 213,297 (Chitty 1992:6).

In Manchester

In 1875 the School Board was conducting five schools with an average attendance of 1,151 pupils; seven years later it was responsible for 16,849 pupils in 38 schools, 13 of which had been built by the Board, the rest having been purchased or transferred. The average number of pupils present weekly at all elementary schools in the city (both board and voluntary) rose by 20,000 in a decade - from 30,581 in 1871 to 50,855 in 1881. It was chiefly children between the ages of five and eleven, previously often running wild in the streets, who were effectively brought into school and, therefore, under the control of local authorities (Simon 1965:113).

By 1896 board schools had an average national attendance of around 1,900,000. Voluntary schools' average attendance was just over 1,200,000 in 1871 and had doubled by 1895. By 1900, nearly half the children who attended public elementary schools were in board schools: in large urban areas the proportion was often much higher.

Although the voluntary and public elementary schools were rival systems in one respect, they formed a socially coherent system in another respect: the identification of this system with the working class did not alter in the remainder of the nineteenth century and was only slowly eroded in the twentieth century (Lawson and Silver 1973:318).

When a Tory/Liberal Unionist government was returned to power in 1895, those opposing the board school system gained the upper hand. AJ Balfour (1848-1930), Leader of the House and First Lord of the Treasury, complained about the 'intolerable strain' to which voluntary schools were subjected.

In 1896 the new government introduced a bill which proposed raising the school leaving age and making new grants for secondary education. But it also offered increased aid to church schools while restricting the activities of School Boards. The Labour movement protested: the Independent Labour Party began demanding secular, as opposed to unsectarian, education, though it was not entirely united on this stance; and Trades Councils across the country declared that the bill was an attack on religious liberty and popular education (Simon 1965:159-160).

Liberals, supporting nonconformist interests, also opposed the bill, arguing against the proposed repeal of the Cowper-Temple clause; the school boards objected to the proposal that secondary education should be outside their control; and even some government supporters were against it, fearing that it would lead to higher rates for education.

In the event, the government dropped the bill, but introduced a new one a year later: the 1897 Voluntary Schools Act (8 April) was limited to providing further subsidies for church schools. 'It was in this year that the TUC first adopted a militant policy covering the whole field of education. The forces were beginning to line up for a decisive struggle' (Simon 1965:161).

The Cockerton Judgement

Hostility to the school boards continued, however, focused on the fact that some of them had 'significantly altered the legislators' original concept of elementary schooling in terms of buildings, equipment, curricula and age range' (Chitty 2007:19) by establishing 'higher tops' (advanced classes) and even separate higher grade schools for older pupils who showed ability and commitment. A few had gone still further and created a new type of evening school for adults. Hostility to the school boards continued, however, focused on the fact that some of them had 'significantly altered the legislators' original concept of elementary schooling in terms of buildings, equipment, curricula and age range' (Chitty 2007:19) by establishing 'higher tops' (advanced classes) and even separate higher grade schools for older pupils who showed ability and commitment. A few had gone still further and created a new type of evening school for adults.

Leading Conservatives, notably Sir John Gorst (1835-1916) (pictured), Conservative Vice-President of the Committee on Education, began attacking the school boards for what they regarded as inappropriate use of the rates. An influential committee was formed to 'combat the School Boards' and, in particular, to 'undermine the advanced work' they were sponsoring (quoted in Chitty 2007:19).

In 1899, Gorst's private secretary Sir Robert Morant (1863-1920) engineered a test case in which a School of Art in London complained of competition from evening classes run by the London School Board. The District Auditor - Cockerton - ruled that the London School Board could not use the rates to fund higher-grade classes in science and art. The famous 'Cockerton Judgement', as it became known, was of profound importance, because it 'sealed the fate of advanced, or secondary, teaching fostered by the more radical and enterprising School Boards' (Chitty 2007:19).

The London School Board appealed twice against the ruling, but it was upheld on both occasions. As an interim measure, the Board of Education established, by Minute dated 6 April 1900, a new system of 'Higher Elementary Schools' (of which more in the next chapter). But it was clear that a new education act was needed to regularise the situation. In the meantime, the 1901 Education Act permitted the boards to continue funding higher tops and higher grade schools for one further year.

In the Cockerton Judgement, Morant and Gorst had achieved their first objective: to prevent school boards from funding anything but elementary schools.

Their second objective - to create all-embracing local education authorities and provide much-needed public cash for the church schools - was achieved by the 1902 Education Act, which Morant drafted. (He went on to become Permanent Secretary of the Board of Education in April 1903.)

The elementary schools

The elementary schools provided by the boards

were intended to and did rest on the same central assumption as the voluntary schools which they were called on to supplement - they were for the children of the poor, providing an independent system for the lower class (Lawson and Silver 1973:318).

Blyth argues that elementary schools were 'a whole educational process in themselves and one which is by definition limited and by implication inferior; a low plateau, rather than the foothills of a complete education' (Blyth 1965:21). They

- catered for children up to 14;

- were for the working class;

- provided a restricted curriculum with the emphasis almost exclusively on reading, writing and arithmetic (the 'three Rs'), largely as a result of the 1862 Revised Code;

- pursued other, less clearly defined, aims including social-disciplinary objectives (acceptance of the teacher's authority, the need for punctuality, obedience, conformity etc);

- used the monitorial system, whereby a teacher supervised a large class with assistance from a team of monitors who were usually older pupils.

Elementary education was widely criticised.

Scottish scientist and Liberal politician Lyon Playfair (1818-1898) complained that the poor quality of science teaching was 'impoverishing the land. It is disgracefully behind the age in which we live, and of the civilization of which we boast' (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:330).

John Ruskin (1819-1900) bemoaned the lack of creativity in the curriculum:

Commiserate the hapless Board School child, shut out from dreamland and poetry, and prematurely hardened and vulgarised by the pressure of codes and formularies. He spends his years as a tale that is not told (quoted in Lawson and Silver 1973:330).

Other writers - notably Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) and TH Huxley - were equally concerned, and their views, coupled with the growth of public interest in education, persuaded the Committee of Council on Education to expand the curriculum of elementary schools.

The Code of 1871, for example, made provision for a special grant in respect of each individual scholar who passed a satisfactory examination in not more than two 'specific' subjects of secular instruction beyond the three Rs. At the same time the list of specific subjects was extended to include foreign languages, various branches of pure and applied science, or any definite subject of instruction extending over the classes to be examined in Standards IV, V, and VI. (The 1871 Code also introduced an infant stage - see Infant schools below).

In 1875, a further step was taken by the introduction of 'class' subjects - grammar, geography, history and plain needlework - for which additional grant was paid. Later Codes, especially that of 1880, extended the list of these class subjects which, if taught at all, had to be taught throughout the whole school above Standard I.

The curriculum of an elementary school from 1875 to the later 1890s thus consisted of three main parts:

Obligatory subjects:

the three Rs ('the elementary subjects') plus needlework for girls;

Optional subjects:

class subjects (for the whole school above Standard I); and

specific subjects for individual scholars in Standards IV to VI.

The 1876 Education Act provided for a system of certificates, which gave free education for three years to pupils who had passed the Standard IV examination at 10 years of age and held a certificate of regular attendance for five years. This arrangement lasted for only five years, but several leading witnesses who gave evidence to the Cross Commission in 1888 (of which more below) spoke of the useful results of the system while it was in operation, and it seems to have helped considerably in the development of higher classes - 'tops' - to many elementary schools.

Conclusions

Of the school boards, Armytage argues that:

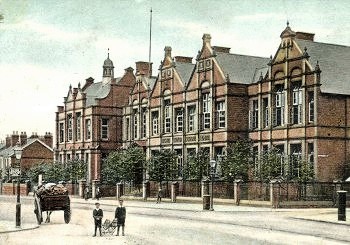

Nothing presents an apter architectural embodiment of the ideas of the Liberals of 1870 than the old board schools, which, blackened now by three-quarters of a century of soot, stand gauntly above the drab Victorian streets. Solid, stone-built structures, they are often compared to prisons. But the more discriminating will notice that the windows were many and large, and there were invariably tiles of good Hanley pottery half-way round the walls. They represented 'the order, system and cleanliness' that were to be brought to bear upon a generation that otherwise would have been dwarfed by the factories. This was the most efficient factory act yet passed, for it did bring the children into schools for part of their lives (Armytage 1951:80).

As to the significance of the 1870 Act itself, Brian Simon writes:

With the Education Act of 1870 reorganisation of the country's educational system was completed in the light of the new conditions following the extension of the franchise. It had not been originally envisaged that the workers' education should be so extended; least of all that control of schools be handed over to elected bodies and the teaching of religion made optional. But events had forced the pace and mass working-class pressure contributed to ensuring that at least the first foundations of a universal system were laid - that education was no longer a charity but a right (Simon 1974:365).

Three more Acts

The remaining years of the nineteenth century saw a raft of legislation which added detail to the state education system the 1870 Act had begun. In this respect, the two most significant Acts were the Elementary Education Act of 1880, which made school attendance compulsory, and that of 1891, which made elementary education free.

In the meantime, three Acts built on the foundation which the 1870 Act had provided.

The 1873 Elementary Education Act (5 August) made some amendments to the 1870 Act, mostly of a technical nature.

The 1876 Elementary Education Act (15 August) sought 'to make further provision for Elementary Education'. Its provisions related to:

- parental responsibility for the education of children (section 4);

- the employment of children under 10 (5-9);

- the payment of school fees for poor parents (10);

- the care of neglected children (11);

- penalties for non-compliance with a school attendance order (12);

- industrial schools (13-17);

- parliamentary grants (18-20);

- by-laws requiring school attendance (21-23); and

- various other administrative matters.

The 1879 Elementary Education (Industrial Schools) Act (11 August) extended the powers of school boards in relation to the establishment and extension of industrial schools.

1880 Elementary Education Act

Despite these moves towards elementary education for all, the attitude of parents to schooling was still very much affected by social and occupational factors. Many working-class parents saw the value of schooling for their children, but 'there remained concentrations of those who were most unlikely ever to see that their offspring obtained an adequate education - unless compelled to do so' (Stephens 1998:86). Some of these were so poor that they could not manage without their children's work or wages; others, notably in some mining and manufacturing districts, 'were well able to afford schooling, but were indifferent to it or saw no need of more than a hasty acquisition of the rudiments, since good wages could be earned by the illiterate' (Stephens 1998:87).

It became obvious, therefore, that the achievement of universal schooling of a reasonable standard would require 'not only the provision of extra schools but the imposition of compulsory attendance' (Stephens 1998:87).

In 1880 Mundella was appointed Vice-President of the Committee in Council on Education, a post he held for five years. He immediately used his new position to push for compulsory elementary education.

The 1880 Elementary Education Act (26 August) (the Mundella Act) obliged local authorities (as designated by the 1876 Elementary Education Act) to make by-laws requiring school attendance, and provided for penalties in cases where 10-13 year olds were illegally employed. It thus effectively established in practice the universal education which the 1870 Act had declared in principle.

Hitherto compulsion had been permissive - i.e. the school boards (set up in 1870) and the school attendance committees (set up in 1876) were allowed to make by-laws enforcing attendance at school. But many of them, fearing the loss in earning power of child labour, had still not done so. Mundella's Act declared they should do so 'forthwith'. If the local authority did not comply by the end of the year 1880, the department themselves would frame the by-laws. Moreover, it made the employer of any child between the ages of ten and thirteen liable to a penalty if that child had not a certificate of education as laid down by these by-laws (Armytage 1951:204-5).

Action was swift: two days after the Act received the royal assent, circulars were sent to all the authorities which had not passed attendance by-laws.

Within five months over 1,200 sets of by-laws were sanctioned, and by January 1881 only twenty-eight unions, eighty-one school boards, one school attendance committee and one urban sanitary authority had not complied. With these minute exceptions the whole population were compelled to send their children to school (Armytage 1951:205).

The 1880 Act was 'another milestone in advance' (Armytage 1951:205). The fifth standard became the minimum standard required for the exemption of ten-year-olds from compulsory school attendance. (The 1878 Factory and Workshop Act (section 26) had empowered 'a Secretary of State, with the consent of the Education Department' to set the required standard for such exemption.)

Furthermore, the so-called 'dunce's certificate', which had allowed less-able children to leave school at ten once they had completed 250 attendances, was no longer available except for children of thirteen years and over, 'and even then the child was required to attend school half-time for another year' (Armytage 1951:205).

1882 Mundella Code

Having achieved his aim of making elementary education compulsory, Mundella now turned his attention to a consideration of what was actually being taught in the schools, and on 2 August 1880 he announced his intention of bringing in a new Code of Regulations.

It proved to be a lengthy task. A code committee, presided over by Mundella himself, spent a year considering proposals which were then submitted to parliament. Armytage argues that 'even more significant than the changes he made was the way he made them, which marked the end of the autocratic tradition of Robert Lowe' (Armytage 1951:210).

Funding for the new code was approved in March 1882. Lord Frederick Cavendish, Financial Secretary to the Treasury, wrote to Mundella:

I shall write to you to-day accepting your proposed changes in the code as satisfactory. We should have been very sorry if we had been obliged to make any difficulties about a scheme which seems to have been worked out with great care and judgement (quoted in Armytage 1951:210).

Mundella's work was recognised by the Royal Society, whose Council unanimously elected him a Fellow.

The Mundella Code 'blazed new trails' (Armytage 1951:211). Though the system of payment by results remained at its core,

a great deal was done to moderate the rigours of the ordeal that is so well described in Jude the Obscure, where an examining inspector enters the room and the teacher falls on her face in a dead faint (Armytage 1951:211).

In infant schools, ninety per cent of the grant still depended on examinations, but 'manual employments and play' were now recognised (Armytage 1951:211), and inspectors noted that this led to a huge improvement in junior schools.

At the upper end of the age range, the provisions in the 1876 and 1880 Education Acts regarding attendance by-laws had resulted in a large increase in the number of children remaining at school up to and beyond the age of 13. To meet the needs of these pupils, the Mundella Code added a seventh standard, 'with a syllabus that made possible its separation into a school of higher grade' (Armytage 1951:212).

Perhaps the most important feature of the new code, however, was the introduction of the 'merit grant'. This was designed to promote more intelligent teaching by eliminating the 'wasteful allotment of the government grant to mere elementary grind' (Armytage 1951:212). Schools were to be classified as 'fair', 'good' or 'excellent' for the purpose of allocating the grant, and inspectors were provided with instructions to guide them in their assessment:

An excellent school is characterised by cheerful yet exact discipline maintained without harshness or noisy demonstration of authority. Its premises are cleanly and well ordered, its timetable provides a proper variety of mental employment and of physical exercise; its organisation is such as to distribute the teaching power judiciously, and to secure for every scholar, whether he is likely to bring credit to the school or not, a fair share of instruction and attention.

Where circumstances permit, it also has its lending library, its savings bank, and an orderly collection of simple objects and apparatus adapted to illustrate the school lessons, and formed in part by the co-operation of the scholars themselves (Report of Committee of Council Instructions to Inspectors, 1882-3:158, quoted in Armytage 1951:212).

Three other points about the Mundella Code are worth making.

First, it made grant payments dependent on the average attendance of the whole school, rather than on that of individual children. As a result, more children were presented for examination and this 'led to a better appreciation of what was actually being taught in the school' (Armytage 1951:212).

Second, new subjects - including science and, for girls, cookery - became eligible for grants:

Elementary science was recognised throughout the school. More attention to English and physical geography was ensured by a rearrangement of the list of class subjects. Specific subjects were extended to include electricity and magnetism; heat, light and sound; chemistry and agriculture. For girls, cookery appeared as a grant-earning subject. In the teaching of these the emphasis was to be on explaining the common objects of everyday life (Armytage 1951:212).

Inspectors were to impress on managers and teachers that 'the more thoroughly a teacher is qualified for his position by skill, character and personal influence, the less necessary is it for him to resort to corporal chastisement at all' (Report of Committee of Council Instructions to Inspectors, 1882-3:158, quoted in Armytage 1951:212).

And third, 'the most essential novelty about the Mundella Code was that it was not unalterable' (Armytage 1951:213). A permanent committee was established to review aspects of the code and, for the first time, instructions to inspectors and other requirements of the department were published in one volume which became 'part of the equipment of every school' (Armytage 1951:213).

The effects of the Mundella Code were far-reaching. 'Machinery had been devised by which it could be perpetually criticised and reconstructed' and 'it profoundly affected the status and work of inspectors, teachers and children' (Armytage 1951:213).

The code placed new burdens on inspectors. As a result of their increased workload, described as 'somewhat alarming' by one inspector (quoted in Armytage 1951:213), the inspectorate was reorganised into ten districts, each with a chief inspector reporting to the department; a new class of sub-inspector was created; and the first woman inspector was appointed 'as a consequence of the introduction of cookery' (Armytage 1951:213).

The code also highlighted the inadequacy of teacher training. Some progressive school boards had already established pupil-teacher centres but had been criticised for doing so because, under the previous code, pupil-teachers were supposed to be trained in the schools. Now, central instruction was officially encouraged and within four years eleven pupil-teacher centres were open, catering for 1,636 pupils who undertook a limited amount of teaching (Armytage 1951:213). Furthermore, new local university colleges were opening, and they 'still further sapped the idea of "apprenticeship" in the training of a teacher' (Armytage 1951:214).