|  |

|  |

Education in the UK Preliminary pages

Organisation of this chapter Background

1990-92 Kenneth Clarke

1992-94 John Patten

1994-97 Gillian Shephard

Labour in opposition

1997 General election

|

Education in the UK: a history Derek Gillard first published June 1998

© copyright Derek Gillard 2018

A printer-friendly version of this chapter can be found here. Citations

References

Documents

© Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland. Background

John Major

He became Tory leader and Prime Minister on 28 November 1990, following Thatcher's resignation.

During his first year in office, his decision to involve Britain in George Bush's Gulf War in March 1991 was controversial, but his government began the long process of bringing peace to Northern Ireland and, despite the Tories' growing divisions over Europe, it successfully negotiated the Maastricht Treaty in December 1991.

Major led his party to a historic fourth general election victory on 9 April 1992, albeit with a much-reduced Commons majority of 21, but his new administration quickly ran into problems. Following the disastrous events of 'Black Wednesday' in September 1992, it was forced to withdraw Britain from the Exchange Rate Mechanism, costing the country billions and the Tories their financial credibility.

At the 1993 Conservative Party conference, Major launched his 'Back to Basics' campaign, which was widely interpreted as a call for a return to 'Victorian' moral values. Sadly for him, the campaign was undermined by a series of scandals involving members of his government and he was criticised by colleagues for his weak leadership. In June 1995 he challenged his critics by resigning and standing for re-election, easily beating his only opponent, the right-winger John Redwood.

Nonetheless, his government was doomed. The Labour Party, rebranded 'New Labour' and with Tony Blair as leader, won a landslide victory at the general election on 1 May 1997.

Major continued to serve as MP for Huntingdon until his retirement from active politics in 2001.

Education

From Margaret Thatcher, John Major inherited an education system which had suffered a significant decline in investment and a corresponding increase in inequality. Many hoped that his government would be less harsh than its predecessor. They were to be disappointed: his administration was equally committed to selection and elitism; equally determined to continue diminishing the role of the local authorities; and equally confrontational in its attitude to the teaching profession.

Clyde Chitty argues that Major's philosophy of education was

The education department was twice renamed during this period. The Department of Education and Science (DES) became the Department for Education (DFE) in April 1992, and then the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE) in July 1995. The Secretaries of State were:

Secretary of State for Education and Science:

Secretary of State for Education:

Secretary of State for Education and Employment:

November 1990 - April 1992: Kenneth Clarke

Kenneth Clarke

In 1970 he entered Parliament as MP for Rushcliffe in Nottinghamshire, and was opposition spokesman on Social Services between 1974 and 1976.

He held several ministerial posts in Margaret Thatcher's governments, becoming Secretary of State for Health in 1988.

He was appointed education secretary on 2 November 1990, just a month before John Major replaced Margaret Thatcher as prime minister. He held the post until the general election in April 1992, when he became Home Secretary and, in May 1993, Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The curriculum

National Curriculum

In an interview with Brian Sherratt on 27 June 1994, Clarke said that one of his first priorities on becoming education secretary was to 'get in the final bits of the National Curriculum, which was rolling through this cumbersome process we had created' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:155). He realised he had the power to make changes to the recommendations of the various subject groups before issuing the Curriculum Orders.

He was also concerned that the subject committees had been 'subjected to far too much lobbying from outside interest groups' and that this had led to an overloading of the curriculum, which was 'massive' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:156).

Implementation of the National Curriculum testing regime began in 1991. For schools, this took the form of SATs, variously referred to as Standard Assessment Tasks, Standard Assessment Tests or Standard Attainment Tests. The first Key Stage 1 tests were conducted in the summer term 1991:

The same could not be said of the secondary school tests which, said Clarke, were 'hopelessly over-elaborate' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:157):

As noted in the previous chapter, the 1988 Education Reform Act had set out new rules on religious education (RE) and collective worship (school assemblies):

offer advice to SACREs, agreed syllabus conferences, and LEAs who wish to consider the desirability of drawing up attainment targets and programmes of study for religious education in their authority, and to offer advice on their construction (NCC 1991:1).The paper included:

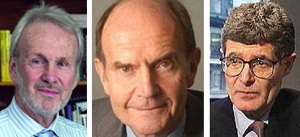

Background By the end of 1991, a general election was looming and Labour was ahead in the opinion polls. John Major and Kenneth Clarke believed that a return to streaming and old-fashioned teaching methods in primary schools would be a popular campaign policy, so Clarke enlisted the support of the media in launching an 'attack against Plowden and all it stood for' (Wrigley 2014:25). Child-centred approaches were to be replaced by traditional 'chalk-and-talk' teaching.  In order to provide some authoritative theoretical underpinning for the campaign, Clarke commissioned Robin Alexander, Jim Rose and Chris Woodhead (pictured, left to right) to produce a discussion paper on Curriculum Organisation and Classroom Practice in Primary Schools. Announcing the appointments on 3 December 1991, he said their report would be published by the end of January 1992. The time of year, and the choice of three men to write it, inevitably led to its becoming popularly known as the 'Three Wise Men Report'. Robin Alexander (1941- ) had been educated at the Perse School and the universities of Cambridge, Durham, London and Manchester. He had taught in schools and colleges before becoming Professor of Education at Leeds (1977-95) and Warwick (1995-2001). He went on to hold a variety of posts at Cambridge and York, and became Director of the Cambridge Primary Review in 2006. Jim Rose (1945- ) had trained as a teacher at Kesteven College in Lincolnshire. He had held several primary school posts, including two headships, and had worked on the Nuffield Science Project at Leicester's School of Education. He had joined HMI in 1975, becoming Chief Inspector of Primary Education and then Director of Inspection for Ofsted. He retired in 1999, but was later invited to lead several reviews, including the 'Rose Review' of the Primary Curriculum in 2009 (see chapter18). Chris Woodhead (1946-2015) had attended Wallington County Grammar School in Surrey and read English at Bristol and Keele. After holding a number of teaching posts, he had moved into teacher training, becoming a tutor on the Postgraduate Certificate of Education (PGCE) course at Oxford. His later career included administrative posts in Devon, Shropshire and Cornwall; he was chief executive of the National Curriculum Council (NCC) from 1991 to 1993, and of the School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA) from 1993 to 1994. In 1994 he was appointed head of Ofsted (more on this below). The three were asked to review the available evidence about education in primary schools and to 'make recommendations about curriculum organisation, teaching methods and classroom practice appropriate for the successful implementation of the National Curriculum particularly in Key Stage 2' (DES 1992:1). The report Curriculum Organisation and Classroom Practice in Primary Schools: A discussion paper, argued that there was evidence of falling standards in some 'important aspects of literacy and numeracy' (DES 1992:1). The progress of primary pupils had been 'hampered by the influence of highly questionable dogmas' (DES 1992:1); in particular, Piaget's notion of 'learning readiness', as set out in the Plowden Report, had had the effect of 'depressing expectations and discouraging teacher intervention' (DES 1992:18). Teachers should be instructors rather than facilitators and, while they should employ a range of organisational strategies including individual and group teaching, there should be more use of whole-class teaching. There was a place for well-planned topic work, but greater emphasis should be put on the subjects of the National Curriculum. More specialist teaching was needed in the upper years of Key Stage 2, and the initial training, induction and in-service training (INSET) of teachers should take account of these needs, because many primary teachers were not equipped to teach subjects effectively and there was an acute shortage of specialist expertise. There should be greater flexibility in the deployment of staff as specialists, generalists, semi-specialists and generalist-consultants. The authors asked: Can a generalist reasonably be expected to profess expertise across a curriculum of the scope and complexity of that now required by law at Key Stages 1 and 2? (DES 1992:8).Pupils should be grouped by ability in subjects ('setted') rather than as a whole class ('streamed'), but 'teachers must avoid the pitfall of assuming that pupils' ability is fixed' (DES 1992:27). The National Curriculum should be regularly reviewed to ensure that it made appropriate demands on pupils of different ages and abilities and that it was manageable in terms of the time, resources and professional expertise available in schools. The authors concluded by expressing the hope that the issues they had raised would be widely debated: It goes without saying that all the observations we offer and the changes we recommend have one over-riding purpose: achieving the highest quality of teaching for all the children in our primary schools. Since this purpose is also shared by those who provide for primary education and teachers themselves we are confident that they will readily accept the invitation we now extend to discuss and address these issues (DES 1992:54).Clarke released the text of the report to the press in late January, two weeks before it was due for publication on 5 February. This meant that its intended audience (ie all those involved in primary education - teachers, trainers, governors and parents) did not have the opportunity to participate in the debate the report calls for, until after the topic had been fully exposed to media hype and distortion (Thomson 1992:64).And it was from that 'hype and distortion' that Robin Alexander was anxious to dissociate himself, according to The Independent on Sunday (2 February 1992). Reaction The Three Wise Men Report caused considerable controversy. Teachers who had been brought up on Plowden regarded it as an attack on their most dearly-cherished values and practices. The two reports shared some things in common, however. Both were products of their age: Plowden, the progressive sixties; Alexander, Rose and Woodhead, the new age of National Curriculum subjects and testing. Both, too, were widely misquoted and misrepresented, often by people who had not read them. There were some genuine concerns, however. Liz Thomson, Deputy Principal at Bishop Grosseteste College, had two main criticisms: first, that the authors had omitted 'any real discussion about the relationship between Key Stages 1 and 2', so that 'we are given the distinct impression that the advent of specialist approaches could well result in a two tier approach to primary education' (Thomson 1992:65). And second, that the report lacked a sense of vision. She concluded: If we as a profession accept uncritically the statements about primary practice and the recommendations of the 'three wise men', we will lose what is best in primary education through our own sins of omission.However, she added, the three wise men should not be criticised too harshly. Their paper had been produced in just seven weeks and, 'unlike the Magi, they did not have a guiding star for illumination' (Thomson 1992:66). Writing in The Guardian (5 August 2008), Peter Wilby suggested that the three wise men had disagreed on a number of issues: by all accounts, the 'wise men' of 1991 were split and Rose sat on the sidelines while the two protagonists, Chris Woodhead, later head of Ofsted, and the educational researcher Professor Robin Alexander slugged it out (Wilby 2008).Whether the publication of the report contributed to the Tories' victory in the 1992 election is open to debate. It was certainly not, as Major and Clarke had hoped, a resounding endorsement of traditionalist views. Teacher appraisal The 1991 Education (School Teacher Appraisal) Regulations (1991 No. 1511) (24 July) required local education authorities (in respect of maintained schools) and governing bodies (of grant-maintained schools) to secure that the performance of teachers was regularly appraised. DES Circular 12/91 School Teacher Appraisal (24 July) provided local education authorities and schools with guidance on implementing the Regulations.

Teachers' pay and conditions 1991 School Teachers' Pay and Conditions Act The 1991 School Teachers' Pay and Conditions Act (25 July) established a teachers' pay review body, replacing the Interim Advisory Committee on School Teachers' Pay and Conditions, which had been set up in 1987. The new body, whose members would be appointed by the Prime Minister, was to examine and report on such matters relating to the statutory conditions of employment of school teachers in England and Wales as may from time to time be referred to the review body by the Secretary of State (Section 1(1)).It would make recommendations regarding the remuneration of teachers 'and such of their other conditions of employment as relate to their professional duties and working time' (1(2)). The Secretary of State would 'give directions to the review body as to considerations to which they are to have regard and as to the time within which they are to report' (1(4)). The Act gave the Secretary of State extensive new powers. He could make provision by order giving effect to the recommendations of the review body, with or without modification, or making such other provision with respect to the matters referred to the review body as he thinks fit (2(1)).In other words, he could, if he chose to do so, simply ignore the advice of the review body. Grant-maintained schools would not necessarily have to comply with pay and conditions orders: the Act allowed their governing bodies to apply for exemption (3(1)).

Ofsted 1992 Education (Schools) Act Having imposed the National Curriculum and its associated testing regime, the government now turned its attention to the third element in its reform of the education system: the inspectorate. From now on, school inspections would be conducted by privatised inspection teams overseen by the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) though, strangely, this was not named in the Act. The 1992 Education (Schools) Act (16 March) made provision for the appointment of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Schools in England (section 1), who would inform and advise the Secretary of State about 'the quality of the education provided by schools' (2) and make an annual report (4). A corresponding appointment would be made for Wales (5). Section 9 provided for the regular inspection of county, voluntary, special, grant-maintained and independent schools; city technology colleges, city colleges for the technology of the arts; and maintained nursery schools. Inspectors would be required to report on (a) the quality of the education provided by the school;All school inspectors would need to be registered (10). Inspection of religious education in voluntary and grant-maintained denominational schools would be conducted by a person chosen by -Faith schools would thus be subject to two complementary inspections: a 'Section 9' inspection (which became Section 11 in the 1996 School Inspections Act) covering the National Curriculum and other matters such as equal opportunities and health and safety, and a 'Section 13' inspection (Section 23 in 1996) covering the religious education under the control of the governors and foundation bodies.(a) the foundation governors, in the case of a controlled school; and Local authorities would retain the right to run their own inspection services and could submit tenders for work in other authorities, provided that 'the full cost of providing the service is recovered by way of charges made by the authority to those using the service' (14). The Secretary of State could require any governing body of a maintained school, or proprietor of a private school, to provide information (16). Schedule 2 to the Act set out the arrangements for school inspections: Every inspection shall be conducted by a registered inspector with the assistance of a team (an 'inspection team') consisting of persons who are fit and proper persons for carrying out the inspection (Schedule 2 Section 3(1)).Each inspection team was to include at least one member 'without personal experience in the management of any school or the provision of education in any school' (Schedule 2 Section 3(2)). These became known as 'lay inspectors'. Every inspector was required to complete a course of training approved by the Chief Inspector (Schedule 2 section 4); and governing bodies were, if possible, to arrange for parents to meet the inspection team (Schedule 2 section 6). Following an inspection, the registered inspector would be required to submit a report (and a summary of it) to the governors, the local authority (in the case of maintained schools), and the Secretary of State. Copies of the report were to be made available to the public (Schedule 2 section 9). Governing bodies were to prepare a written statement ('the action plan') of the action which they propose to take in the light of [the] report and the period within which they propose to take it (Schedule 2 section 10).In the case of a school 'considered to be at risk', the Secretary of State could require that implementation of the school's action plan should be monitored (Schedule 2 section 11). Ofsted came into being on 1 September 1992, with Stewart Sutherland (1941-2018) as the first Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Schools (HMCI). (Previously, the head of HMI had been known as Senior Chief Inspector.) Sutherland, a Scottish academic and religious philosopher, had been appointed Vice Chancellor of London University in 1990. The first round of inspections was due to take place in 1993, as John Patten noted in a House of Commons written answer: OFSTED - the Office for Standards in Education - opened on 1 September 1992. Her Majesty's chief inspector, Professor Stewart Sutherland, and his staff are now preparing for the first round of second school inspections to start in September 1993 (Hansard House of Commons 20 October 1992 Vol 212 Col 265W).Reaction Ken Jones has argued that Ofsted was 'in one sense the product of two decades of Conservative critiques of state education, but in another it was the very reverse of their ideals' (Jones 2003:115). It carried out 'detailed and often unsympathetic inspections of schools' (Jones 2003:133). For Professor Denis Lawton, Director of the London Institute of Education, the 1992 Education (Schools) Act was 'little short of disastrous' because it reduced HMI, which had had 'a distinguished history', to a 'rump' which would act as 'a kind of quality control within Ofsted' (Lawton 2005:110). The Labour Party was concerned about the effect of privatising 'a particularly sensitive part of the education service', and about the cost-effectiveness of Ofsted - which did, indeed, prove to be 'extremely expensive' (Lawton 2005:110). The establishment of Ofsted did little to raise teachers' morale. They quickly discovered that an inspection involved huge amounts of paperwork and form-filling; they were suspicious of the motives and abilities of some of the private contractors; they found the week of the inspection itself extraordinarily stressful; and they had concerns about the accuracy and fairness of some of the published reports - which was understandable, given that their careers were at stake. The style of inspection became more like an inquisition, so much so that teachers began to dread Ofsted visits, not necessarily because they were unsure about their own competence, but because masses of paperwork were required before, during and after an inspection (Lawton 2005:110).Teachers did manage to find amusement in some aspects of the process, however, such as the inclusion of a 'lay inspector' in every inspection team. The joke in school staffrooms was that to be a lay inspector you had to know nothing about education. In September 1994, Stewart Sutherland was replaced as HM Chief Inspector of Schools by Chris Woodhead who, two years earlier, had been one of Kenneth Clarke's 'three wise men' (see above). Woodhead appeared to take a positive delight in criticising teachers and, as a result, became something of a hate figure in schools up and down the country. Teacher morale deteriorated even further when government ministers began using Ofsted reports as a basis for 'naming and shaming' so-called 'failing' schools. In his interview with Brian Sherratt in 1994, Kenneth Clarke explained why the Tories had felt it necessary to create Ofsted. The 'old schools inspectorate' (HMI), he said, didn't inspect a lot of the schools at all, except on a very, very infrequent basis. It regarded its most important role as developing ideas on policy of its own and advising ministers about those ideas; so they were keener on their input to ministerial policy than they were on changing anything in the schools themselves. And they didn't report very openly, except in broad-brush terms on matters of general policy all the time. They were very supportive of the schools, and in the main they were very good people. But the independent inspectorate reorientated the whole outfit and gave it a role that fitted the reforms (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:153-4).Clarke's successor as education secretary, John Patten, agreed. He told Brian Sherratt in May 1994 that HMI were people who'd achieved some distinction in the teaching profession. They were able to go into classrooms, report on exactly what they saw, and make their assessments on the basis of the nationwide experience they had from going into classrooms across the whole country. They still are. But the cycle of HMI inspections meant that out of 23,000 schools in the system, only 200 a year had a full inspection; at that rate it meant that a secondary school would get inspected once every forty years before Ken's reforms, and a primary school once every two hundred years. Now it's every school, as you know; in striking contrast, it's once every four years (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:183).Furthermore, HMI reports had focused mostly on 'what teachers were doing rather than on what pupils were achieving - on inputs rather than outputs'; and when the reports were published - as they had been since Keith Joseph 'took that bold decision some ten years ago' - there was 'no way of ensuring that appropriate action was taken' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:183). Ken Clarke changed all that. He put in place a system which would ensure that all schools were inspected with the rigour of the 200, that the standards schools achieved were set out in full, that they took any action necessary to improve performance, and that the governing body and senior management were accountable (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:183). Further and higher education The government published two education White Papers in May 1991: the first, Education and Training for the 21st century, dealt with further education; the second, Higher Education: A New Framework, with higher education. Each had a laudable aim: the first, to 'end the artificial divide between academic and vocational qualifications' (DES 1991a:ii); the second, to abolish the 'binary divide' or 'binary line' - the 'increasingly artificial distinction between universities on the one hand and polytechnics and colleges on the other' (DES 1991b:4). Some of the White Papers' other aims were contentious, however. The first proposed the removal of colleges from local authority control: LEAs would 'no longer have a role' (DES 1991a:Vol II:39); and both sought to turn further and higher institutions into independent businesses which would have to compete for students and funding. 1991 White Paper: Education and Training for the 21st century The White Paper Education and Training for the 21st century was published in two volumes. (References in this section are to Volume I except where otherwise shown.) It began by declaring that: The school reforms introduced under the Education Reform Act are already strengthening the education system for pupils up to the age of 16. Youth Training has been transformed. We plan to build on these reforms, so that a fully-integrated system of education and training exists which allows steady progression from school through to further and higher education, and to training in work. Our policies will promote continuous learning from the age of 5 through education and throughout working life (DES 1991a:3).The government's aims - 'of engaging more young people in education and training, and raising their attainment' - would 'require improvement throughout the system' (DES 1991a:3). It therefore proposed to:

The Government intends to legislate to remove all colleges of further education, which offer a minimum level of full-time or part-time day release education, from local authority control.From 1 April 1993, colleges would be funded directly by the government, through new Councils to be 'appointed by and responsible to the Secretaries of State for Education and Science and for Wales' (DES 1991a:59). A new funding regime would be 'designed to provide a powerful incentive to recruit additional students and reduce unit costs. ... There are great opportunities for increased participation and efficiency gains' (DES 1991a:59). Although it was not spelt out in the White Paper, it was clear that the government expected the colleges to compete for students: they would be 'free to respond to their customers' and would thus be encouraged to be 'efficient' and 'effective' (DES 1991a:64). The colleges would work closely with the Training and Enterprise Councils (TECs), which already had specific responsibilities for work-related further education. Over the following decade, the government's policies would create a modern system of academic and vocational qualifications, both of a high standard and both highly valued, which offer ladders of opportunity right through from school to work and throughout working life [and]The government attached great importance to systems which would ensure the quality of education and training provided by the colleges. Of the three existing levels of quality assurance - the colleges themselves, the examining and validating bodies, and the external assessors - the roles of the first two would be 'unchanged by the new arrangements' (DES 1991a:Vol II:38); but the new funding Councils would have responsibility for: a) ensuring that quality systems in general form a satisfactory basis for the funding being provided: responsibility for quality flows from responsibility for finance; andPresenting the White Paper (and that on higher education) to the House of Commons on 20 May 1991, Kenneth Clarke said: The White Paper sets out in detail the Government's proposals for further education colleges and sixth-form colleges. As I announced to the House on 21 March, we intend that those colleges will become autonomous institutions outside local authority control.Labour's shadow education secretary, Jack Straw, replied: The Secretary of State has just confirmed the removal from local control of the 557 further education, tertiary and sixth-form colleges of England and Wales and their enforced transfer to centralised control from Whitehall. Is the Secretary of State aware of the enormous opposition that those plans have aroused within his own party? What is his response to the views of many local authority Conservative leaders, including Mr. Tim MacNamara, the leader of Hampshire county council, who said on Friday that the Secretary of State was hell bent on destroying local education authorities without any idea of what to put in its place'; who complained of the Secretary of State's 'government by denigration', and who said these changes were blighting all planning of 16 to 19 education? Was not the same Mr. MacNamara correct to accuse the Secretary of State of acting 'for wholly doctrinal reasons'? ...The White Paper was 'generally considered to be unsatisfactory' (Lawton 2005:109), The Independent (21 May 1991) describing it as a 'Timid Tory Plan for Training'. The Labour Party favoured a more radical solution involving a broader curriculum, while the left-leaning think-tank, the Institute for Public Policy Research (lPPR), recommended the creation of a British baccalaureate. 1991 White Paper: Higher education: A new framework In his Foreword to Higher Education: A New Framework, Prime Minister John Major wrote: In higher education, our key reform will be to end the increasingly artificial distinction between universities on the one hand and polytechnics and colleges on the other. This will build on our plans to transform education and training for 16-19 year olds by removing the barriers between the academic and vocational streams (DES 1991b:4).The White Paper announced 'changes in the five main areas which currently seal the binary line in place', namely:

it is in the interests of universities, polytechnics and colleges to continue to look for increased levels of funding from private sources in particular from industry and commerce, from benefactors and alumni, and from present sources of fee income. Such private income can enhance considerably the independence of individual institutions. The Government accepts that public funds will remain the main source of income for funding the projected expansion of student numbers (DES 1991b:10).The existing 'separate channels' for the funding of teaching in universities on the one hand and polytechnics and colleges on the other would hinder efficient further expansion of higher education provision. The government therefore proposed to introduce 'a single funding structure for teaching in universities, polytechnics and colleges' (DES 1991b:14). With regard to the funding of research, the White Paper set out the following principles:

Arguments for 'complete coherence' pointed in favour of 'one single Funding Council operating across Great Britain or the United Kingdom as a whole' (DES 1991b:21). However, the government intended to introduce separate Funding Councils for higher education in England, Scotland and Wales. To ensure fair competition across territorial boundaries, the funding allocations by each territorial Secretary of State to the relevant body will be informed by the Government's general policy on higher education. Subject to that, funding will take account of each particular set of territorial circumstances, such as the different structure and duration of degree courses in Scotland (DES 1991b:22)The Open University would, for funding purposes, be 'brought within the ambit of the new Funding Council for England' but would 'retain its general UK mission' (DES 1991b:23). With regard to the quality of teaching and learning, there was a need for 'proper accountability for the substantial public funds invested in higher education'; and students and employers needed 'improved information about quality' if the full benefit of 'increased competition' was to be obtained (DES 1991b:24). The White Paper listed five 'aspects of quality assurance in higher education':

Finally, with regard to pay and conditions of service, employers in higher education would be expected 'to settle their own negotiating arrangements' in the light of the White Paper's proposals. The government would 'continue to influence pay and conditions of service through the level of funding provided for the new Higher Education Funding Councils' (DES 1991b:35). Commenting on the White Paper in his 1994 interview with Brian Sherratt, Clarke said what seemed to me mad was to have two totally different systems of distributing money, and relationships with the Department, with bodies all of whom would have been called a university in other countries in the world. ... I thought we could devise for the lot of them parity of esteem, parity of status, and a system which was a fairer way of distributing the money for teaching and research, and would encourage and bring the best out of all of them (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:158-9). 1992 Further and Higher Education Act Proposals from both these White Papers were incorporated into the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act (6 March); the 1992 Further and Higher Education (Scotland) Act (16 March) provided for similar arrangements in Scotland. Part I of the Act, dealing with further education, provided for the establishment of Further Education Funding Councils (FEFCs) (Section 1); and removed further education and sixth form colleges from local authority control (11). For Benn and Chitty, the removal of the local authorities from the further education sector was a damaging development. The colleges - now 'further education corporations' - would be subjected to 'quango-funding and control through a privatised market' (Benn and Chitty 1996:14). Furthermore, local authorities would no longer be able to develop strategic plans: there were to be no local systems, only individual education 'businesses' competing with one another for 'customers' within the centrally controlled legislative framework (Benn and Chitty 1996:14).Part II of the Act dealt with higher education. It ended the 'binary divide' between the universities and other providers - the colleges and polytechnics - by making them all 'higher education corporations', funded by new Higher Education Funding Councils (HEFCs) (62), which replaced the Universities Funding Council and the Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council (63). It also abolished the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA) (80). Following the Act, the polytechnics and the Scottish central institutions all became universities, almost doubling the number of universities in the UK. In 1993 the larger colleges of the University of London effectively became independent universities when they were granted direct access to government funding and the right to confer degrees; the constituent institutions of the University of Wales were later given the same rights.

1992 General election Conservative manifesto In its section on 'Schools, Pupils and Parents', the Conservative manifesto for the 1992 election, The Best Future for Britain, stressed the importance of choice and diversity and promised a 'Parent's Charter': Under the Parent's Charter, all schools will have to provide at least one written report on the progress of each child each year. Information on the performance of all local schools will be given to parents, enabling them to exercise choice more effectively.It promised the completion of the ten-subject National Curriculum; 'regular and straightforward tests' for all 7-, 11- and 14-year-olds by 1994; the creation of more nursery places; and the publication of 'full information ... about the performance of all local schools in each area'. Popular schools which were over-subscribed would be 'given the resources to expand'; and grant-maintained schools would be able to 'change their character'. The Assisted Places scheme would continue to give 'access to independent education to many families who could not otherwise afford it'. The 'partnership between the state and the churches in education' would be strengthened. The Tories promised to 'reinforce the professionalism of teachers and the esteem in which they are held'. There would be 'regular appraisal of teachers', and 'reform of the teacher training system to make it more effective in developing classroom skills'. Sixteen-year-olds would be 'free to choose between college, work-based training and sixth form studies'. The 'well-respected A-level examinations' would be defended; and there would be improvements in vocational education, including a new General National Vocational Qualification (GNVQ). A Conservative government would 'continue to expand the number of students in higher education' and abolish 'the artificial "binary line" between universities and polytechnics'. (This had already been legislated for by the time of the election.) The introduction of student loans had given students '30 per cent more money for their living costs than the former system of grants alone', and the government would 'continue to provide generous support for students and to expand our student loans commitment'. Finally, the 'training revolution' which the Tories had initiated would continue 'to create a framework within which men and women of all ages can develop skills, gain qualifications and shape their own futures'. Labour manifesto Meanwhile, the Labour manifesto, It's time to get Britain working again, included a section on 'Raising standards in our schools'. It declared that: Good education is the best investment in Britain's future. All girls and boys, from every background, must be able to discover their talents and fulfil their potential.The manifesto noted that 'Britain today invests a smaller share of our national wealth in education than in 1979', and that 'more and more parents are now being forced to pay for essentials in a system which should be free'. Labour would provide an additional £600m for education over two years and then 'continue steadily to increase the share of Britain's national wealth invested in education'. There would be more nursery places and a nationwide childcare strategy. Education standards would be raised through 'better teaching, smaller classes and modern books and equipment'. Within 12 months, we will end the scandal of primary school classes of over 40 children. We will then establish and steadily reduce maximum limits on class sizes, until no primary school child is taught in a class of more than 30.Increased funding would be provided for class and library books, equipment and laboratories. 'We will start to tackle the backlog of school repairs. For instance, we will invest £30 million to ensure that within 12 months, no child has to use an outside lavatory'. Teachers would be 'guaranteed a proper salary and career structure'. A General Teaching Council for England and Wales would be created to raise professional standards; there would be 'higher quality training' and better support for newly-qualified teachers. A national Reading Standards Programme would be established, with a Reading Recovery Programme 'to help those in difficulty'. There would be better provision for children with 'special needs or special abilities'. With regard to selection, the manifesto said: Nine out of ten secondary school children are in comprehensive schools. We will end selection at 11 where it still exists. We will introduce a fairer system for all school reorganisations, with independent public enquiries. We will phase out the Assisted Places scheme (without affecting pupils currently on a place, or offered one from September 1992) and redirect the savings to meet wider educational needs.Instead of the Conservatives' privatised schools inspectorate, there would be an Education Standards Commission which, together with HMI, would 'monitor the performance of every school'. All schools would be 'free to manage their day-to-day budgets'; local education authorities would be given 'a new strategic role'; grant-maintained schools would be 'freed from central government control'; and they, and the city technology colleges, would be brought into 'the mainstream of the local school system'. An unexpected outcome Although opinion polls had predicted a narrow Labour victory, the Conservatives won the general election on 9 April 1992 with a Commons majority of 21. Some political commentators suggested that Labour's defeat was a result of the party's commitment to raising income tax; others argued that it was due to Neil Kinnock's poor judgement in staging, on the eve of the election, a triumphalist rally in Sheffield which many found distasteful. Teachers who had hoped for a more constructive, less confrontational, approach to education were profoundly disappointed. Following the election, the Department of Education and Science (DES) was renamed the Department for Education (DFE) and John Patten was appointed Secretary of State for Education.

1992-1994: John Patten

John Patten

Brought up as a Catholic, Patten attended the Jesuit-run Wimbledon College and then read geography at Sidney Sussex College Cambridge. He taught at Oxford (1969-1979), becoming Fellow and Tutor at Hertford College in 1972.

He entered Parliament as MP for the City of Oxford in 1979, moving to Oxford West and Abingdon in 1983 following boundary changes. He held a number of junior ministerial posts at the Northern Ireland Office and in the Ministry of Health, served as Minister of State for Housing, Urban Affairs and Construction (1985-87) and then became Minister of State at the Home Office.

His appointment as secretary of the renamed Department for Education (DFE) in April 1992 was 'unexpected' (The Independent 13 February 1993). He was to preside over

He was arrogant and tactless: he described representatives of the National Association of Parent-Teacher Associations as 'neanderthals' (The Independent 13 February 1993); and, three weeks after becoming education secretary, he launched an extraordinary attack on Birmingham's Chief Education Officer, Tim Brighouse, telling a party conference fringe meeting: 'I fear for Birmingham, with this madman let loose, wandering the streets, frightening the children.' Brighouse sued, and won a substantial out-of-court settlement, which he donated to educational charities (The Guardian 24 April 2007).

Patten became a life peer following the 1997 general election.

'Selection' becomes 'specialisation'

Patten was as keen as John Major to undermine the comprehensive system, but he realised that public support for comprehensive schools was a problem - one which even Thatcher had been unable to solve. There had been widespread parental opposition to the reintroduction of selection in the wake of the 1979 Education Act; the number of schools choosing to adopt grant-maintained (GM) status had been disappointing; and few firms had agreed to sponsor city technology colleges: the fifteenth and last of these - Kingswood City Technology College in Bristol - had been given approval in April 1991.

A new strategy was needed. Patten's solution was to convert 'selection' into 'specialisation'. In an article in the New Statesman and Society (17 July 1992), he argued that:

Such schools are already emerging. They will, as much more than mere exotic educational boutiques, increasingly populate the educational landscape of Britain at the end of the century, a century that introduced universal education at its outset; then tried to grade children like vegetables; then tried to treat them ... like identical vegetables; and which never ever gave them the equality of intellectual nourishment that is now being offered by the National Curriculum, encouraged by testing, audited by regular inspection. (Patten 1992:20-21 quoted in Chitty and Dunford 1999:27)

1992 White Paper: Choice and Diversity

Patten ignored the critics and described his White Paper, Choice and Diversity: A new framework for schools, published in July, as a 'landmark' which would decide the shape of schooling for the next quarter century.

The government believed that school autonomy and parental choice, combined with the National Curriculum, were together 'the keys to achieving higher standards in all schools' (DFE 1992:15). A single new body, the School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA), would replace the National Curriculum Council (NCC) and the School Examinations and Assessment Council (SEAC).

A Funding Agency for Schools would be created as part of 'the evolution of a new organisational framework for the education service' (DFE 1992:19). As more schools became grant-maintained, the Funding Agency would take over the responsibilities of local education authorities (LEAs).

School admission arrangements - to be 'exercised increasingly at the school level' - would be designed to 'secure the maximum parental choice possible' (DFE 1992:28). Grant-maintained schools and LEAs would be encouraged to cooperate on admissions, but the Secretary of State would be able to impose common procedures if necessary.

LEAs would be required to increase delegation to their schools under their schemes of local management, and would be able to 'supply support services to GM schools on competitive terms' (DFE 1992:31). The government would 'maintain and strengthen the partnership between the state and the Churches and other voluntary bodies in both LEA maintained and GM schools' (DFE 1992:31).

Chapter 8 of the White Paper was devoted to spiritual and moral development. The government would

With regard to pupils with special educational needs, the White Paper declared that they should be educated in ordinary schools 'to the maximum extent possible' (DFE 1992:40).

The government wished to see 'much greater diversity and specialisation by schools, particularly in technology, while still ensuring that the full National Curriculum is offered to all pupils'. The 'developing network of specialist Technology Schools, with CTCs at its centre', would be extended through the Technology Schools Initiative (DFE 1992:43).

A separate chapter dealt with implementation of these proposals in Wales.

Most of the White Paper, however, was devoted to strategies to persuade more schools to opt out of local authority control and become grant-maintained. It claimed that there had been 'rapid and successful growth in the number of grant-maintained schools' (DFE 1992:19). In fact, in the four years following the 1988 Education Reform Act, there had been just 428 decisive 'opt-out' ballots in England and Wales, of which 331 were in favour (Chitty 2009a:56). In Scotland, only one school had chosen to become grant-maintained (Fisher 1993a:24).

The government therefore proposed a series of measures which it clearly hoped would increase the number of grant-maintained schools:

This is the Government's vision for education in this country. This White Paper is another important step towards its realisation (DFE 1992:64).

Similarly, the White Paper declared that Uniformity in educational provision presupposes that children are all basically the same and that local communities have essentially the same educational needs. The reality is that children have different needs. The provision of education should be geared more to local circumstances and individual needs: hence our commitment to diversity in education (DFE 1992:3-4).Critics argued that the White Paper could more appropriately have been titled 'Chaos and Perversity'. Its central policy - that of 'diverting more money away from LEAs into schools which were encouraged to become more and more market oriented' - was criticised not only by Labour, but by the press and even by moderate Conservatives for over-emphasising choice, especially in the form of grant maintained schools that were free from local authority interference (Lawton 2005:110).Ann Taylor, the newly-appointed shadow education secretary, objected to the White Paper's punitive approach to school improvement (Lawton 2005:111). In Don't sell pupils short, an article for the Roman Catholic paper The Tablet (10 October 1992), Patten explained that he had devoted a whole chapter of his White Paper to 'Spiritual and Moral Development' because he believed that 'schools must not be value-free zones' (quoted in Tombs 1994:86). Six months later, the National Curriculum Council published its contribution to the debate about national morality and the part schools could play in developing it. Spiritual and Moral Development a discussion paper (April 1993) argued that 'Schools should be expected to uphold those values which contain moral absolutes' (NCC 1993:4) and it listed these as:

The White Paper's proposals formed the basis of the 1993 Education Act (27 July). Published in two volumes totalling 290 pages containing 308 sections, it was the largest piece of legislation in the history of education. Its first five parts covered: I Responsibility for education

The local authorities In the second of his interviews with Brian Sherratt (on 6 June 1994), Patten was asked how he saw the future role of local education authorities, given that the 1993 Act provided for the Funding Agency for Schools (FAS) to take over many of their responsibilities as the number of grant-maintained schools increased. He replied that, in some local authority areas, the FAS will be in total charge because more than 75 per cent of the places in the secondary sector are grant-maintained; so in those areas the LEA has a more residual role. No one has to have an LEA, a Local Education Authority, any more after the 1993 Act. I think in one or two areas they're looking at putting some of the functions of the LEA together with some of the functions of the Social Services Department and, where there are Housing Authorities, Housing as well, with a kind of all-singing, all-dancing service providing a sort of role (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:192-3).Sex education In 1991, the National Curriculum Science Orders had been revised to include teaching at Key Stage 3 about HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and AIDS (Acquired Immunity Deficiency Syndrome), which had become a major public health issue during the 1980s. However, Patten and his deputy, Emily (Baroness) Blatch (1937-2005), seem to have been 'profoundly influenced' (Chitty 1994a:17) by campaigns led by the pressure group Christian Action Research and Education and the fundamentalist Plymouth Brethren sect. Both groups called for a ban on compulsory sex education in schools and the removal of all mention of HIV/AIDS from the National Curriculum. The result was Section 241 of the 1993 Education Act, which

The right to withdraw children from lessons must be maintained until the sex education lobby shows itself both willing and capable of promoting responsible attitudes towards sexual behaviour, marriage and family life (quoted in Chitty 1994a:17).The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) and the children's charity Kidscape disagreed. NSPCC policy officer Eileen Hayes warned: there is a potential danger that if parents were abusing a child and had the right to remove it from sex education lessons for whatever reason, it might be an advantage to keep that child in ignorance ...Right-wing attitudes to sex education were not shared by the vast majority of parents. A survey conducted by the Health Education Authority, reported in The Times Educational Supplement (4 November 1994), found that 94 per cent of parents supported sex education in schools, with 80 per cent in favour of schools teaching about HIV and AIDS. Only one per cent of parents intended to withdraw their children from the lessons. There seemed to be 'general confidence in the role of teachers in the whole area of sex education', though this view was 'not shared by a quarter of Muslim parents and 17 per cent of Hindus' (Chitty 1995:19). In 1987, DES Circular 11/87, Sex education at school, had said: The Secretary of State considers that the aims of a programme of sex education should be to present facts in an objective and balanced manner so as to enable pupils to comprehend the range of sexual attitudes and behaviour in present day society; to know what is and is not legal; to consider their own attitudes, and to make informed, reasoned and responsible decisions about the attitudes they will adopt both while they are at school and in adulthood (DES 1987b:4).This paragraph, argues Chitty, 'clearly had the hand of HMI on it' (Chitty 1995:19). On 6 May 1994, Patten issued Circular 5/94, Education Act 1993: Sex Education in Schools, which set out a 'moral framework for sex education': The Secretary of State recognises that sex education ... should lead to the acquisition of understanding and attitudes which prepare pupils to view their relationships in a responsible and healthy manner. It must not be value-free; it should also be tailored not only to the age but also to the understanding of pupils. ... schools' programmes of sex education should therefore aim to present facts in an objective, balanced and sensitive manner, set within a clear framework of values and an awareness of the law on sexual behaviour. Pupils should accordingly be encouraged to appreciate the value of stable family life, marriage and the responsibilities of parenthood. They should be helped to consider the importance of self-restraint, dignity, respect for themselves and others, acceptance of responsibility, sensitivity towards the needs and views of others, loyalty and fidelity. And they should be enabled to recognise the physical, emotional and moral implications, and risks, of certain types of behaviour, and to accept that both sexes must behave responsibly in sexual matters. Teachers need to acknowledge that many children come from backgrounds that do not reflect such values or experiences. Sensitivity is therefore needed to avoid causing hurt and offence to them and their families; and to allow such children to feel a sense of worth. But teachers should also help pupils, whatever their circumstances, to raise their sights (DFE 1994b:6).Rachel Thomson, Information Development Officer of the Sex Education Forum, argued that the problem with sex education in Britain was that it had become totally politicised. 'People on the political Right see sex education as an opportunity for social engineering', she told The Observer (7 November 1993). 'They are worried about recent changes in sexual behaviour and see sex education as a chance to turn the clock back' (quoted in Chitty 1995:20). For Clyde Chitty, it was a source of much regret that the Government should have made such an unholy mess of giving schools and teachers sound advice on the all-important area of sex education. This is surely a part of the curriculum where young people should be encouraged to talk freely about values, emotions and relationships. The price of pupil ignorance is the very state of affairs that the Government claims to want to change (Chitty 1995:20).Religious education The new provisions relating to religious education and collective worship were set out in Sections 254-259 of the 1993 Education Act and explained in Circular 1/94 Religious Education and Collective Worship, published by the Department for Education on 31 January 1994. An unusually long and detailed Circular (63 pages), it set out the legal responsibilities of head teachers, governors, local authorities, SACREs, agreed syllabus conferences, teachers, and teacher trainers in the light of the 1993 Act. The Circular said: Every school must by law provide religious education and daily collective worship for all its pupils, with the exception of those pupils who are withdrawn from these activities by their parents. It is a matter of deep concern that in many schools these activities do not take place with the frequency required or to the standard which pupils deserve. The Government's aim is therefore to improve the quality of the religious education curriculum for pupils in order to ensure that they have the best possible opportunity to develop through this area of the curriculum (DFE 1994a:9).At the same time, the School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA), which had replaced the National Curriculum Council, issued guidance for Standing Advisory Councils on Religious Education (SACREs) in the form of National Model Syllabuses for RE. On the day these were published, the London Evening Standard welcomed the increasing focus on Christianity as part of the government's social agenda: Ministers believe the move will underscore the need to restore traditional family values and help reduce the number of schoolchildren involved in crime (Evening Standard 25 January 1994).Writing in Forum (Autumn 1994), David Tombs, lecturer in Theology and Religious Studies at Roehampton Institute, argued that New Right social interests continue to underpin the government's attempts to influence and control religious education. Two concerns may be identified in the development of government attitudes to religious education. First, pressure for religious education to be predominantly Christian; second, emphasis on moral instruction in Christian values. These developments can only be fully understood when the New Right ideological agenda behind them is recognised (Tombs 1994:85).Despite the White Paper's title Choice and Diversity, the clear impression was that 'in government eyes moral education [is] concerned with authority and conformity far more than personal choice and cultural diversity' (Tombs 1994:86). National Commission on Education

When the government refused, Moser set up the independent National Commission on Education (NCE), funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and chaired by Lord Walton of Detchant. The Commission's final report, Learning to succeed: a radical look at education today and a strategy for the future, published in 1993, listed seven main goals:

The aims of giving all children access to 'high-quality' schooling and of creating greater choice and diversity were simply not compatible: As we see it, the main task for the future will not be to concentrate on producing highly educated elites, but to achieve higher learning outcomes for all, and particularly for those in the middle and lower bands of attainment. ...Clyde Chitty found the NCE report disappointing. Reviewing it in Forum, he noted that there was only one reference to comprehensive schools in the index: The Report cannot bring itself to come out unequivocally in favour of a major prerequisite of future advance: the establishment at the secondary level of a national system of community comprehensive schools with no selective or independent enclaves (Chitty 1994b:61).The Commission's hope that its vision for the future would be shared by the government was 'wishful thinking of a rarefied kind' (Chitty 1994b:61): Nothing that has happened in the past fifteen years gives one any cause to expect that any significant part of the National Commission agenda for change will be implemented by John Major and his miserable team at the DFE (Chitty 1994b:61). National Curriculum The National Curriculum had been designed and constructed with very little input from practising teachers: they had been prevented from being curriculum innovators and demoted to being curriculum 'deliverers'. Based on discrete subjects, it made integrated 'topic' and 'project' work difficult; it was hugely overloaded with content, so that its introduction had resulted in falling standards in some 'important aspects of literacy and numeracy' (DES 1992:1); and its assessment procedures were cumbersome, to say the least. With the government's promise (in its 1992 election manifesto) that 'information about the performance of all local schools' would be published, three inevitable - and undesirable - effects quickly became apparent:

the simplification and 'Anglicisation' of the national testing system, so as to emphasise basic skills and the English cultural heritage (Jones 2003:141).The New Right gained control of the curriculum and assessment councils, where they provoked strong opposition from teachers, especially from teachers of English. By the spring of 1993, teachers were considering a boycott of English tests for 14-year-olds (The Independent 13 February 1993); and there was a widespread boycott of Standard Assessment Tests (SATs) in 1993-4. As a result, Patten was forced to commission a review of the National Curriculum and, in April 1993, he appointed Sir Ron Dearing to lead it. 1994 Dearing Review

He was asked to 'undertake a Review of the National Curriculum and of the framework for assessing pupils' progress' (Dearing 1994:3) and, in particular, i the scope for slimming down the curriculum;Dearing produced an interim report in July 1993; his final report, The National Curriculum and its Assessment, was submitted to Patten on 20 December 1993 and published in 1994. It argued that the National Curriculum was 'fundamental to raising educational standards', but that Urgent action is needed to reduce the statutorily required content of its programmes of study and to make it less prescriptive and less complex (Dearing 1994:7).The statutory curriculum Orders should therefore be subject to a 'closely co-ordinated review' (Dearing 1994:7) with a view to i reducing the volume of material required by law to be taught;Key Stages 1-3 At Key Stages 1-3 (for pupils aged 5-14), the content of the curriculum should be reduced so that twenty per cent of teaching time would be 'for use at the discretion of the school' (Dearing 1994:21). The first priority for this discretionary time should be to support work in the basics of literacy, oracy and numeracy; schools should be accountable to their governing bodies for using the time released effectively. The School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA) should review the attainment targets and statements of attainment with a view to reducing their number. 'No further major changes should be made to the National Curriculum Orders for five years following the review' (Dearing 1994:9) Appendix 6 of the review set out advice to primary schools on how the level of record keeping, which had been 'a heavy burden for many teachers' (Dearing 1994:14), could be reduced. Dearing himself is said to have reckoned that a primary teacher might have to assess pupils against up to one thousand attainment statements in a year; his review 'provided some relief to teachers who were drowning in assessment requirements' (Wrigley 2014:24-25). However, the pressure was still heavy, especially for teachers of younger primary pupils, and it had damaging results: 'the statutory requirement to report attainment levels in every subject, and multiple strands in some, inevitably distracted from their traditional focus on teaching children to read' (Wrigley 2014:25). Key Stage 4 At Key Stage 4 (ages 14-16), schools should have greater opportunity to offer a curriculum which meets the distinctive talents and individual aspirations of their students. The mandatory requirements should be limited to English, mathematics and single science, physical education and short courses in a modern foreign language and technology. Religious education and sex education must, in addition, be taught by law. Careers education is also particularly important at this key stage (Dearing 1994:9).Dearing 'justified the abandonment of Key Stage Four in the form envisaged in 1987' (Chitty 2013:135) on the grounds that it would allow 'greater scope for academic and vocational options' (Dearing 1994:9). He called for 'the development of three broad educational pathways in post-16 education and training' (Dearing 1994:19):

Dearing expanded on these proposals in an address to the Secondary Heads Association's annual conference in Bournemouth in March 1994, when he announced that 14-year-old students would soon be able to study for qualifications in one or other of five vocational areas: manufacturing, art and design, health and social care, leisure and tourism, and business and finance (The Financial Times 21 March 1994 quoted in Chitty 2013:136). Special needs The National Curriculum should be available to pupils with special educational needs, and special needs teachers should be involved in its revision (Dearing 1994:11). Assessment With regard to assessment, Dearing argued that The ten-level scale is unnecessarily complex and excessively prescriptive. It suffers from duplication and inconsistencies. These failings explain some very real problems teachers have experienced in implementing the National Curriculum (Dearing 1994:11).However, the purposes the scale was intended to serve were sound, and it should therefore be retained but improved, with i a substantial reduction in the number of statements of attainment to provide a definition of what is expected at each level, which is sufficiently clear and rigorous to be of use to teachers but which avoids the excessive detail of the present approach;The national tests in the core subjects should be simplified 'as far as possible without sacrificing validity and reliability'; and 'the time which is needed to administer the tests must continue to be reduced' (Dearing 1994:13). Systems of moderated teacher assessment should underpin standards but should not be bureaucratic or require excessive amounts of teacher time; for Key Stage 3, statutory teacher assessment of non-core subjects should be introduced or reintroduced. The Group set up by SCAA to advise on the value-added approach to the measurement of school performance should report by June 1994. Finally, Dearing argued that the ten-level scale was unnecessary 'for the majority of students at Key Stage 4', and he therefore recommended that 'it should not be used at this key stage' (Dearing 1994:70). Outcome The government accepted Dearing's recommendations so that, by the time the Conservatives left office in 1997, the Key Stage 4 curriculum 'bore little resemblance to the framework devised ten years earlier by Kenneth Baker' (Chitty 2013:136). The compulsory subjects in maintained secondary schools were now: English, maths, science, design and technology, information technology (as a separate subject or coordinated across other subjects), a modern foreign language, and physical education. The humanities and arts were demoted to being optional extras: pupils had to choose between history or geography; art or music. Secondary schools also had a statutory duty to provide religious education in accordance with a locally agreed syllabus, and a programme of 'carefully structured sex education' (Chitty 2013:136). Careers education was scheduled to become a statutory part of the secondary curriculum from September 1998. In those parts of Wales where Welsh was spoken, it was an additional 'core' subject. Reaction Myra Barrs, Director of the Centre for Language Education, argued that Dearing had left a 'trail of confusion' behind him, which was 'likely to be most marked at Key Stage 4', where he had 'casually demolished a common system of examining at 16+ which it had taken more than twenty years to establish' (Barrs 1994:36). But the most problematic element in the final report was unquestionably Sir Ron's decision to retain the 10-level scale as the basis for National Curriculum assessment, despite much public agonising about its inadequacies. It is hard to see how we can go on working with a basic framework for assessment which is obviously so deeply flawed (Barrs 1994:36).Ken Jones has argued that, by reducing the amount of detail and removing 'the stronger signs of the traditionalist and ethnocentric enthusiasms of the New Right' (Jones 2003:141), the revised National Curriculum marked the end of the New Right's curricular influence, at the same time as it helped embed the curriculum, and its associated testing system, at the consensual centre of English schooling (Jones 2003:141).Speaking in May 1994, just after the publication of the Review, Patten said: I've added my own twiddles to it; all children between 5 and 7 to have some British history; English to be given close attention in all subjects, whether it's geography or history; if you can't communicate and express yourself in English, then you can't function. We'll have to see what teacher-land makes of it over the next three months, but I think we have got the makings of a settlement now, which I hope will be in place by January next year, when the papers go out to all the schools so they know what they're doing for September 1995 (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:185).He hoped that the next five years (1995-2000) would be a period of peace and quiet where we can concentrate on the outputs; on making sure that the test papers are rigorous enough; against a background of some stability, which I'm sure practising teachers would welcome (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:185).1994 Warwick Evaluation The Dearing Review was not the only manifestation of anxiety about the National Curriculum: there were particular concerns about the teaching of English. There was widespread dissatisfaction with the English component of the National Curriculum from the moment it was introduced in schools in the autumn term, 1990. Six months later the National Curriculum Council (NCC) commissioned the University of Warwick to undertake an evaluation of it: work began in September 1991. To complicate matters, a year later the NCC advised the Secretary of State that the English Order needed revising. The Secretary of State asked the NCC to conduct a review, and this was completed in March 1993. The Warwick project team, led by Professor Bridie Raban, Urszula Clark and Joanna McIntyre, therefore had to conduct their evaluation against this changing background. The Warwick team published an interim report in 1992; their final report, Implementation of English in the National Curriculum, was completed in August 1993 and published in 1994 by the School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA), which had replaced the NCC in 1993. The 'Warwick Evaluation' concluded that teachers had 'welcomed National Curriculum English as a workable framework within which their work with pupils can develop', and that it could be 'strengthened best through further support and sharply targeted guidance' (Warwick 1994:126). It made the following recommendations: